- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

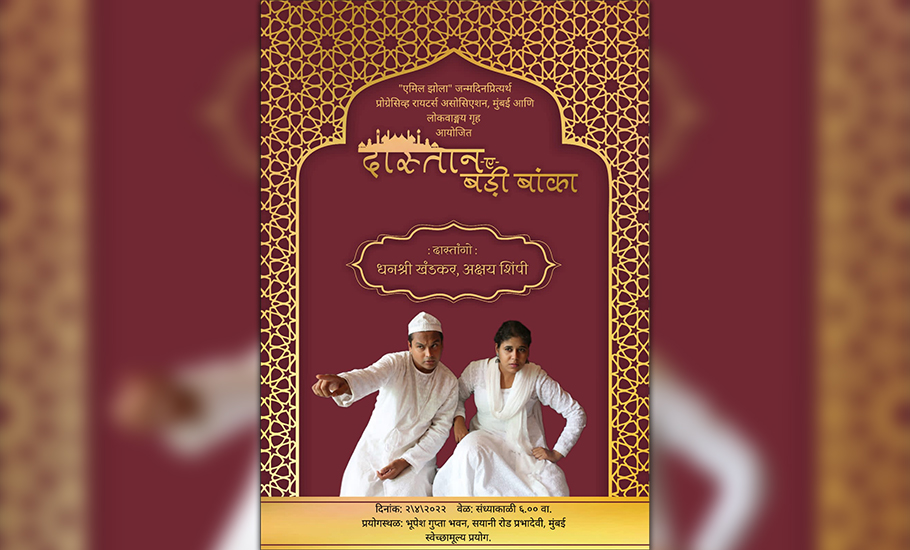

Lights, silence, narration: The enchanting world of dastangoi

The lights are dimmed. The spotlight draws the audience’s focus on the performers. Dressed in traditional white angarakhas, chauri mohri ka (wide-cut) pyajamas and topis, the dastangos (storytellers) sit on an elevated platform side by side, with their knees folded. Two dainty silver bowls, filled with water, are kept on their sides. After their performance is announced, the hubbub of...

The lights are dimmed. The spotlight draws the audience’s focus on the performers. Dressed in traditional white angarakhas, chauri mohri ka (wide-cut) pyajamas and topis, the dastangos (storytellers) sit on an elevated platform side by side, with their knees folded. Two dainty silver bowls, filled with water, are kept on their sides. After their performance is announced, the hubbub of the audience gets shushed. The tellers of tales start regaling the audience with stories of valour and vice, of razm (fight), bazm (feast), tilism (magic) and ayyari (trickery). It’s a mesmerizing journey; the performers hold the audience in a trance through their ornate language, the well-orchestrated modulation of their voices, and vivid expressions. This is how a typical performance of dastangoi, the oral storytelling tradition dating back to the times of Mughal Emperor Akbar which was revived in 2005, unfolds.

Seventeen years after ‘the lost art of storytelling’ was given a new breath of life by eminent Urdu scholar and author Shamsur Rahman Faruqi and his nephew, author and performer Mahmood Farooqui, the storytelling tradition is in the throes of innovation, raring to be in sync with a changing world. In recent years, dastangoi has found favour with people of all hues, cutting across the barriers of language, religion and culture. Originally performed in chaste Urdu, with distinct flavours of Persian, there are now dastangos in Gujarati, Marathi, Punjabi and Bengali, who draw on their own storytelling traditions.

The contemporary dastangos are attracted to dastangoi because of its inherent beauty and mysticism, suspense and magic; they romance the form to bring several worlds into being: the worlds of djinns, jaadugars (wizards) and paris (fairies) as they have been chronicled in Dastan-e Amir Hamza, which arrived in the Indian subcontinent via Persia, and Tilism-e-Hoshruba, the region’s first wholly indigenous Indo-Islamic fantasy epic. The medieval tales of Hamza and Hoshruba, filled with the elements of the occult, fantasy, adventure, and romance, have been reinterpreted by performers across time, and changed form with every telling and retelling.

Tracing the history of the tradition

The original version of Dastan-e Amir Hamza (1883-1917) existed in 46 volumes, each of them approximately a thousand pages long. However, it exists only in one or two special collections and can no longer be found easily. The most popular one-volume version of Dastan-e Amir Hamza was first published by Ghalib Lakhnavi in 1855; it was amended by Abdullah Bilgrami, a compiler of oral dastan like Lakhnavi, in 1871. Both of them rewrote and expanded the story in their own ways. The gist of the story: Amir Hamza, an adventurer in the service of the Persian emperor Naushervan, defeats many enemies, loves several women, and converts hundreds of infidels to the ‘true faith’ before finding his way back to his first love, Mehr-Nigar, the daughter of the emperor.

The complete version of the magical fantasy epic had never been translated into English or any other Western language till Pakistani author Musharraf Ali Farooqi undertook the arduous task. The Adventures of Amir Hamza: Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction, translated by Farooqi, which was published by Modern Library in 2007, captures the epic in all its colourful action and fantastic elements.

The tradition of dastangoi can be traced back to the late 15th century India. According to MA Farooqi, Mughal Emperor Akbar, who suffered from dyslexia, had commissioned a monumental illustration of Hamza-Nama (The Story of Hamza). It was narrated to him in an interesting way; large paintings were held up for him while the story, depicted in those paintings, was narrated to him by a professional standing on the other side of the painting. It is believed that the scriptoriums built for the execution of this project also influenced the course of Indian miniature painting.

MA Farooqi tells us that Emperor Akbar took a particular liking to the tales of Hamza. “He not only enjoyed its narration, but in 1562, he also commissioned an illustrated album of the legend. It took fifteen years to complete and is considered the most ambitious project ever undertaken by the royal Mughal studio. Each of its fourteen hundred, large-sized illustrations depicted one episode and was accompanied by mnemonic text in Persian — the court language — to aid the storyteller. Only ten per cent of these illustrations survived, but the royal patronage popularized the story and the Indian storytellers developed it into an oral tale franchise,” writes Farooqi.

The art travelled across the country for centuries before it almost faded from the social consciousness in the late 19th and early 20th century; the last professional dastango Mir Baqar Ali died in 1928. When it was revived in the cultural spheres of Delhi as a performative art steeped in oral traditions, the idea was to dip into the richness of the storytelling tradition, an exercise in nostalgia. But with contemporary themes woven into it, these dastans bristle with the contemporariness of their themes.

According to MA Farooqi, it was in the late 19th century Lucknow that two rival story-tellers, Syed Muhammad Husain Jah and Ahmed Husain Qamar, wrote a fantasy in the Urdu language, which has never been rivalled since: Tilism-e Hoshruba. “The writers claimed that the tale had been passed down to them from story-tellers going back centuries: it was a part of the beloved oral epic, The Adventures of Amir Hamza which had come to the Indian subcontinent via Persia and had gained in popularity during the reign of Akbar, the Mughal emperor,” writes MA Farooqi in Hoshruba The Land And the Tilism-e Hoshruba: Book 1 (2011).

The Tilism-e-Hoshruba tells the stories of Amir Hamza’s military forces, his grandson and his loyal band of tricksters (masters of wit and disguise) as they go to war with Afrasiyab, the sorcerer who rules the magical land of Hoshruba.

The contemporary touch

Today’s dastangos go beyond performing the traditional dastans of Hamza and Hoshruba to talk about causes close to them through their own dastans woven around contemporary themes. They have simplified these tales and made them more relevant to the contemporary audience. Dastangoi is being enacted today differently by different storytellers: many do so to articulate their social and political concerns or to promote the causes close to their hearts. There are performers with roots in literature, theatre, music and Sufism, who have embraced the form in order to tell the stories that are linked with their craft and lived experience. Dastangos, both men and women, have made the form shine like burnished gold, captivating viewers wherever they have performed. The tribe of storytellers committed to the craft of dastangoi has only been growing in recent years.

Mahmood Farooqui, artist and creator of Dastangoi Collective, is known for giving the form a contemporary touch by drawing on modern literary texts, as well as scripting his own dastans. His recent tales include Dastan-e-Chouboli, adapted from a Rajasthan folk tale, which he has performed with Darain Shahid; Dastaan-e-Partition, performed by Pratap Sen and Rohan Chopra; and Dastan-e-Raza, based on the life and times of the artist, SH Raza.

Farooqui says that while the traditional Dastan-e Amir Hamza contains narratives that remain unsurpassed in their imagination, creativity, drama, suspense and plot turns — all contained in beautiful Shakespearean language — when the audience enjoy them in our time, they become both “relevant and topical”. Along with the traditional dastan, he is also seized by the urge to tell a thousand other stories that need to be told.

“Nobody else is telling the stories from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana the way we do. Dastan-e-Partition, the Dastan-e-Sedition, the Dastan-e-Gandhi, Dastan-e Jalian and Bhagat Singh — all address themes that show our pluralistic tradition and past. It is important to let both Muslims and Hindus know that Muslims have written hundreds of poems, narratives and other works based on Hindu mythology, the Gita and the Upanishads, and vice versa,” he says, underlining that the main imperative of his work is to excavate layers of our past that speak to the contemporary mind. “It is an attempt to wrest back the narrative of divisiveness and enmity and rancour and instead spread the message of peace and reconciliation, drawing from our past,” he says.

Today, as the word dastan is back in circulation in popular culture and dastangoi performances are de rigeur at cultural festivals, Farooqui says that it is this “taken-for-granted existence” which is the greatest success of the Collective and the people associated with it. Spelling out his debt to SR Faruqi, he says: “Dastangoi is now a natural part of our cultural landscape and there is no doubt that it is the barkat, the grace of all the enormous hard work lasting decades that the great Faruqi put into his study of the tradition. His five-volume magnum opus of the study of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza is one of the most outstanding scholarly and literary achievements of post-independent India. It will require more than my lifetime to repay his debt and the debt to the traditional stories and the dastangos of yore.”

The core audience: urban youth

The core audience for dastangoi in this age of distraction is the urban youth. Farooqui’s audience usually comprises the bourgeoisie, the upper middle-classes who do not fully understand Urdu, but are hungry for something new — “for tradition, for learning, for stories that only dastangoi can tell”. He says: “Nobody can tell Kabir or Khusrau or Gandhi or Karna the way we do because dastnagoi is now a performative essay, which comprises storytelling, lecture, research as well as performance. It is a unique form, a new genre of presentation, in a new language”

Dastangoi Collective’s efforts have played a key role in the efflorescence of this ‘lost tradition’. “It is the main body spearheading the revival. There are very few dastangos who have not emerged from the collective, whether they acknowledge it or not,” says Farooqui. The collective organises workshops in schools and colleges and help, guide and counsel anyone who wants to do dastangoi. “We are a study centre, a repertory, an academy all rolled into one,” Farooqui says.

Udit Yadav, one of the performers who learnt the art of dastangoi at the collective, says he was awestruck when he watched Farooqui and Darain perform ‘Dastan Hussam Jaadu Ki” for the first time. “I couldn’t understand a single word for the first 15 minutes. However, the dastan soon took me in its grip and took me on the magical journey; such is the power of the art form. The imagery, drama and flavour of all dastans, particularly of the dastans from ‘Tilism-e Hoshruba’, is astounding,” he says.

Yadav’s interest in literature, culture and heritage led him to discover the world of dastangoi. When he was growing up, his grandfather would narrate stories from the Mahabharata, Ramayana and Panchatantra — as well as poems of Kabir and Tulsi Das — with voice modulation, facial and body movements, often artistically explaining the inherent meanings. “This led to my inclination towards stories and storytelling,” he says. He became an active member of Asmita theatre group and developed a taste for Hindi and Urdu literature during his graduation from Delhi University.

Echoing Farooqui, Yadav says that a major chunk of his audience base is the youth. It may be, he says, because there is an increasing inclination of those in the younger years of their life towards art forms. The romanticization of Urdu, too, has played a role in the popularisation of dastangoi. “We have observed that people now can understand the difficult language of Tilism-e-Hoshruba as they applaud at the right time,” says Yadav.

Weaving in socio-political concerns

Lucknow-based poet and author Himanshu Bajpai, who was brought to dastangoi by the late colossus Ankit Chadha, likes to weave his stories around social and political themes. His musical dastan, Ganga Gaatha, depicts the plight of river Gomti, a tributary of Ganga. In the narrative structure of a dastan, he contrasts the glory accorded to the Ganga in the mythology with the city’s apathy towards keeping it clean. “Kahani sunana apne aap mein ek fun hai (telling a story is an art in itself). But there are some concerns that we have to put out there as thinking individuals,” he tells The Federal. This art acquires a different purpose when it’s combined with a political message. In the age of shrinking space for resistance and dissent, Bajpai is aware that telling the truth can make an artist suffer.

“However, if an artist knows his art, he can use it to register his protest,” says Bajpai, whose other dastans draw on the Kakori conspiracy and the friendship between Ram Prasad Bismil and Ashfaq Ullah Khan; the love for mangoes; the dangers of plastic; and the valour of Rani Lakshmibai. “We are all connected through stories,” says Bajpai, who is currently working on a dastan on Kanwar Digvijay Singh ‘Bapu’, India’s best-known hockey player believed by many to be comparable to Dhayan Chand; 2022 marks his 100th birth anniversary.

Sanchi Peswani, the actor who has worked in films, television and theatre, held the audience enraptured with her rendition of ‘Kholki’, a story of the Gujarati canon, at Kathakar: International Storytellers Festival held in Delhi in May. Written by Tribhuvandas Purushottamdas Luhar (1908-1991), better known by his pen name Sundaram, the story is about a child widow who is married to an older man with three children. “To him, she is only means to an end. To her, however, he is her future, and her life,” says Peswani, who has earlier performed under ‘Dastangoi Gujarati’, an initiative conceived by thespian Hiten Anandpara and run by theatre director Pritesh Sodha and actor Alpana Buch. It was formed in 2018, with an aim to popularise Gujarati writers among the new generation.

“We decided that we must revive the stories that are slowly disappearing from our literary spaces,” says Sanchi, who finds ample scope to emote in a dastan. “You create several worlds in front of the audience. As an actor, you have to be connected with all the voices you bring into being through your story. When you narrate, you try to inhabit the places which are not shown on the stage, as well as the minds of other characters. This means that you keep constantly flitting between different time zones, eras and locations.”

The rhythm of words

Dastango Poonam Girdhani was drawn to the form by its distinctive beauty, philosophy and humour. She was held captive by alfaaz ki khanak (the rhythm of words) when she watched a performance for the first time: “Oral storytelling has its own beauty. But dastangoi goes one step further in form and style. It weaves a rich tapestry of unrestrained imagination.” Moving beyond the stories of Hamza and Hoshruba, Girdhani has prepared and performed ‘Daastan-e-Irfaan-e-Buddh,’ the story of Gautam Buddha’s enlightenment. When she was working on the dastan, she started with a single line of thought: Buddha’s appeal to people not to make him God. She dipped into Jataka tales and the biographies of Buddha to show him as a human being with flaws, someone who acknowledged the right and the wrong when he saw it happening. As a woman working on the dastan, she also brought in Amrapali and Yashodhara, the women in Buddha’s life, into the narrative.

Language is the main aspect of dastans. In Girdhani’s telling, Urdu gets blended with Pali and Sanskrit. “That’s how a dastan acquires jaah-o-jalal (grandeur). You have to find parallels to create a world in which things enter organically,” says Girdhani, who believes that dastans should be the subaltern documentation of our time. Dastangos can’t go on reciting stories that have already been written. “To get a grip on the form, we have to document the present. Unless we do that, we remain incomplete storytellers. We have many shades of voices in the society. Capturing the times is lazmi (essential). A story, ultimately, is about lived experiences. We have a collective pool of memories and we must dive and bring stuff from that pool.” It is with the “dust particles” of society that she wants to create the larger-than-life world of dastans. Girdhani is currently exploring the form through the lived experiences of women dastangos of the past. “Dastangoi was a male-centric activity, but there must have been many women who performed this. Since it has not been documented, I would very much like to explore it.”

As a performer, dastangos create pictures in the mind of the viewers. While in theatre, there is a fourth wall between the performer and the viewers, in dastangoi that wall goes away. A dastango must welcome the engagement of the audience. Girdhani says: “What gives you a kick is the strength of the storytelling, which moves your audience and makes them a part of the performance.”