- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Lights out: The dark truth behind coal mine accidents

Considering that miners work in hazardous working conditions in a high-risk sector, safety is always a concern, say experts and activists.

Late on September 2, a detonator misfired deep inside an underground coal mine in Srirampur area of Telangana’s Mancherial district. Four miners were injured; three of them survived. The fourth one, Ratnam Lingaiah, 54, a coal cutter, had suffered a head injury. After being taken to a local hospital, he was being shifted to a bigger hospital in Hyderabad when he breathed his last. It was...

Late on September 2, a detonator misfired deep inside an underground coal mine in Srirampur area of Telangana’s Mancherial district. Four miners were injured; three of them survived. The fourth one, Ratnam Lingaiah, 54, a coal cutter, had suffered a head injury. After being taken to a local hospital, he was being shifted to a bigger hospital in Hyderabad when he breathed his last.

It was the second incident in recent times. In June, an explosion at an opencast coal mine in Ramugundam in Telangana’s Pedapalli district killed four contract workers. The four deceased were identified as B Rajesh, Arjaiah, Rakesh and B Praveen. The place has nearly 50,000 workers engaged in coal mining operations. located across a 350-km stretch of the Pranhita-Godavari Valley.

Both the mines belonged to state-run Singareni Collieries Company (SCCL). Perhaps due to the recurring incidents, Lingaiah’s family didn’t have to run around for compensation. In fact, the day after the accident the company Singareni Collieries Company (SCCL) gave his family ₹15 lakh as compensation, which had been increased by the government in 2019 from ₹5 lakh.

But the trade unions and employee associations had demanded a judicial probe into the June incident and sought an ex-gratia of ₹1 crore to the families of the deceased and ₹50 lakh to the injured. Even as they were fighting for it, the September accident occurred, claiming the life of Lingaiah.

The two accidents highlighted the poor safety standards in mines run by SCCL, which currently operates 18 open cast and 30 underground mines spread across four Telangana districts.

Telangana, Singareni’s worsening record

The unions and activists highlight the same and accuse the company of procedural lapses.

In June, when the accident occurred in Singareni, The Federal had highlighted the lapses. Company workers had alleged that Singareni’s practice of hiring inexperienced and untrained private contractors in hazardous operations led to such accidents.

The company encouraged private participation in the mining operations to increase profits and production capacity, but neglected the safety of coal miners.

An email sent to the company did not elicit response on the reasons for the accidents and what measures the company took to ensure such cases aren’t repeated.

The SCCL extracts 67 million tonnes of coal every year for power generation in Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra. Besides, coal from the local fields is also supplied to pharmaceutical companies, ceramic, iron and steel industries.

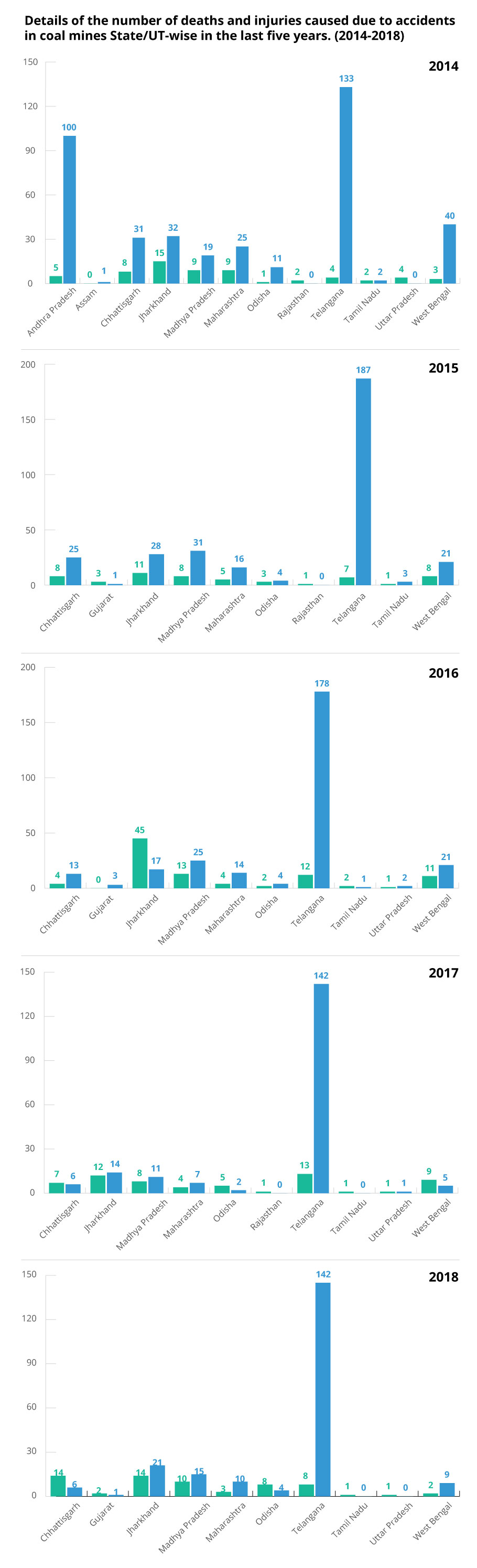

Interestingly, since 2017, about 65% of all the accidents in various legally run coal mines across the country came from one company — SCCL. Also, one in two injured in coal accidents in the country were reported to be from Singareni mines.

This has resulted in Telangana topping the list of states with most accidents, as against its figure of 13% in 2014-18.

In a reply to a question in the Lok Sabha during the monsoon session of the Parliament, the Ministry of Labour and Employment noted that the number of accidents in coal mines in the country was higher than the number of accidents occurring in non-coal mines in the last three years. Historical data also suggests the same — about 50-60% of the accidents occur in coal mines compared to other minerals extractions.

Miners don’t matter

In most of the mines across the country, workers are hired on a contract basis and paid ₹2,000-3000 weekly, and in case of accidents, their families have to run from pillar to post to claim the compensation amount. Some barely get any compensation.

Kengarla Mallaiah of Sinagareni coal mining workers’ association says the company was not doing safety audits rightly and also utilised less money for the safety equipment at the worksites.

As per the government data, only 64% of earmarked budget for safety has been utilised by subsidiaries of Coal India Limited in 2017-18 and 2018-19. It is estimated to be even lower for other mines.

“Considering that miners work in hazardous working conditions in a high-risk sector, safety is always a concern. Let the management conduct independent safety audits and impart safety training to even private contractors in a strict manner,” Mallaiah said.

He further said that the blasting work should not be given to private contractors. “Let an expert team manage and supervise it; why bring in untrained personnel at low cost?” he asked.

He also demanded the company to submit an action taken report, alleging that those responsible for the accidents were let off without any penalty or punishment.

With the government amending the labour laws on Wednesday, which makes it difficult for labour unions to go on a strike without giving prior notice (14 days), mine workers further fear exploitation in the hands of mining companies.

Government turns a blind eye

India is largely dependent on coal for thermal power which accounts for nearly 63% of the overall power generation in the country. Renewable energy stands at just about 22%, with the target to double by 2030.

States like Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha and Madhya Pradesh are heavily dependent on coal, employing a large number of people. Coal-rich states also rank low in social index and economists caution a slow but planned transition to renewable.

Several analyses indicate the lack of adequate and effective standard operating procedures for safety measures, ineffective supervision, shortage of manpower and lack of proper risk assessment as the main reasons.

A large number of mobile mining equipment such as haul trucks, dumpers, tractors, tankers are used for different operations; they reportedly contribute to a significant percentage of fatal and serious accidents.

An analysis of 40-year data (1973-2013) on the causes of fatal accident in coal mines since nationalization of coal mines, by the Department of Mining Engineering, Indian School of Mines, Dhanbad, India, indicates five major causes, such as ground movement, roof fall, use of heavy machinery and usage of explosives contributing almost 91% of the total accidents. The report warned of more accidents if the mining companies didn’t learn from its mistakes.

In the 43rd meeting of the Standing Committee on Safety in Coal Mines, Ministry of Coal, held in August 2018, (under Piyush Goyal,), several issues including shortage and poor of mining shoes and gumboots for workers, shortage of competent manpower, diminishing stature of mine managers (key person for ensuring mine safety), continued practice of manual drilling in most underground mines and the need for increased use of blast free mining technology for enhancing safety and production, were brought up by the trade unions.

Even as 33 countries in the world ratified the International Labour Organisation’s convention 176 on the safety and health in mines, the government of India is yet to ratify the recommendations to protect miners.

Much of these were concerns in the government-owned legally operating mines. The problems were aplenty in illegal mines operating in the country.

The case of Meghalaya

The data above does not reflect the accidents in the Northeast as many were reported from the illegal mines. For instance, despite a ban imposed by the National Green Tribunal (NGT) in Meghalaya on rat-hole mining, digging of small vertical pits to mine minerals, about 17 miners were buried in a rathole mine at Ksan in East Jaintia Hills in December 2018 after it was flooded suddenly due to heavy rains.

After nearly 100 days of rescue operation, the Indian Army and Navy, which were called in after the crisis hit, decided to cease rescue operations on March 2, 2019. By then, only two bodies had been recovered. The operation was one of the longest efforts to rescue miners in India.

In July 2012, a similar accident had led to 15 miners’ deaths in South Garo Hills. Their bodies were never recovered.

In Meghalaya, most of the lands being mined are either privately owned or community owned and had both the surface right and sub-soil right. So the state had little control.

The NGT, which had imposed a fine of ₹100 crore on the state government last year for failing to curb illegal mining, on September 2 issued a notice to the Meghayala government asking them to submit a report within four weeks on the action taken to stop illegal mining, transportation in the state.

Unending misery

Of those who died in the 2018 accident in Meghalaya, three of them — Chaher (Shahir), Amir Hussain and Monirul Islam (18), the youngest of the mine workers in Ksan, were from Assam’s Chirang district. Their families barely got about ₹3 lakh compensation and as reported by The Wire, much of it was spent on commission to get the interim relief, and to pay off the debts taken by the deceased.

One of the villagers, Mustakim says the families are now struggling to make their ends meet and the suspension of the mine operations has worsened the livelihood options for the villagers.

He says even now, many of his villagers are engaged in illegal mining works as they find no other jobs and even the construction labour work pays only half of what they usually get (₹3,000 weekly).

He said rat hole mining continues unabated without much safety precautions amid ban by NGT. The apex court had lifted the scientific method mining ban in Meghalaya last August.

Lingaiah’s 20-year-old son Vishnuvardhan says the welfare officer orally assured him of a job in the mines. A diploma holder in mining engineering, Vishnuvardhan says his dad never spoke of the risks at job despite several accidents being reported in Singareni mines in the past. He is eager to take up the job as the responsibility of his mother and two sisters has now fallen on him.

But they still haven’t got the death certificate nor the post-mortem report from the concerned authorities. The company, police and the health officials are passing the buck on each other and delaying the process.

What needs to be done

Vincent Pala, a mine owner and Member of Parliament who has been vocal about regularising the mining operations in the state, said “regularising” these mines was the only way to make them fall in line to follow the rules.

“The sector has potential to create jobs in the state and by way of regularising, the state can have better control. But with the NGT ban, we do not see it opening anytime soon even as several mine owners have applied to the government seeking permission,” Pala said.

Dilip Kumbhakar of Central Institute of Mining and Fuel Research, Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), says the death rate however has come down over the years and it’s perhaps at the industry’s best, though there’s scope for improvement if the companies follow the SOPs laid down.

“All they have to do is to follow the best practices and standard operating procedures which are laid down. Today, India has about 2 deaths per 1,000 workers employed (0.2 percent) and that’s a good progress compared to three decades before,” he says.