- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Kashmir to Kohima: The muddied pathway to peace talks

On August 14, 1947, a day before India made her tryst with destiny, the Naga National Council (NNC), then an omnipotent political organisation of the Naga people headed by Angami Zapu Phizo, declared Independence for the Nagas. However, the world outside did not immediately get to know about the development as the NNC’s telegram addressed to leading Indian newspapers informing about...

On August 14, 1947, a day before India made her tryst with destiny, the Naga National Council (NNC), then an omnipotent political organisation of the Naga people headed by Angami Zapu Phizo, declared Independence for the Nagas.

However, the world outside did not immediately get to know about the development as the NNC’s telegram addressed to leading Indian newspapers informing about its proclamation of independence was not dispatched by the postmaster of Kohima post office following an instruction from the then-deputy commissioner of the Naga Hills, Charles Pawsey.

Information blackout to suppress dissent has since then become a part of the Indian statecraft and has been used, as recently as in Kashmir. On August 5, the BJP-led Centre announced its decision to abrogate special status to the state under Article 370 of the Constitution and split it into two Union territories — Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh. Communication and travel restrictions imposed since then have been eased only selectively.

The action in Kashmir naturally has repercussions in India’s Northeast, particularly in Nagaland, as states in the region enjoy varied degrees of autonomy under various provisions of the Constitution on the basis of the principle of asymmetric federalism.

Union Home Minister Amit Shah tried to allay apprehensions in the region, assuring that special provisions under Article 371 series would not be touched. Despite the assertion, the apprehension remains.

“We have to understand the motive behind the scrapping of Article 370. The BJP wants to make India a homogenous country as far as possible. In its idea of India, where does Article 371 (A) or other such provision fit in?” asks Chubatemjen Ao, a leading Naga intellectual and former minister.

The suppression of dissent in Nagaland back in 1947, much like the scenes playing out in the Kashmir valley right now, did not prove to be much effective. In the unilateral plebiscite conducted by the NNC on self-determination in May 1951, a whopping 99.9 per cent Nagas reportedly opted for independence. A year after that Naga people boycotted the first general elections of 1952. Not a single vote was cast, former Nagaland chief minister late Hokishe Sema put on record in his book, Emergence of Nagaland: Socio-economic and Political Transformation and the Future.

In March 1953, when India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru visited Kohima with his Burmese counterpart U Nu, the gathering at a public reception turned its back and walked out as Nehru was about to begin his address. The Nagas were enraged as their representatives were not allowed to present a memorandum to the prime minister.

The jackboots

The Indian government did not take the affront lightly and launched a massive crackdown in the Naga Hills. As the NNC started collecting arms for its resistance and going underground, the government responded by mobilising the paramilitary Assam Rifles and subsequently promulgating the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958. The law later went on to become a major bone of contention between security forces and human rights activists wherever it was to be enforced, from Manipur to Jammu and Kashmir.

According to one estimate, nearly two divisions of the Army and 35 battalions of Assam Rifles and Assam Police were deployed in the tiny Naga Hills district of the then undivided Assam. Hundreds of villages were uprooted and shifted to a new location under a policy called “village grouping,” pioneered by the Japanese army in the 1930s.

“…and though there was nearly one security troop for every adult male in the Naga Hills, Tuensang Area, there never was a time when it could be claimed that the Naga guerrillas had been broken into submission. The Naga rebels till then had little training. They had a few arms of odd varieties often taken from dumped stock of the Second World War. Often their snipping was done with the help of muzzle loaders… and yet the Naga guerrillas carried on the fight relentlessly. They suffered terrible deprivations and casualties but did not give in,” recalled former IB chief BN Mullick in his memoir, My Years With Nehru.

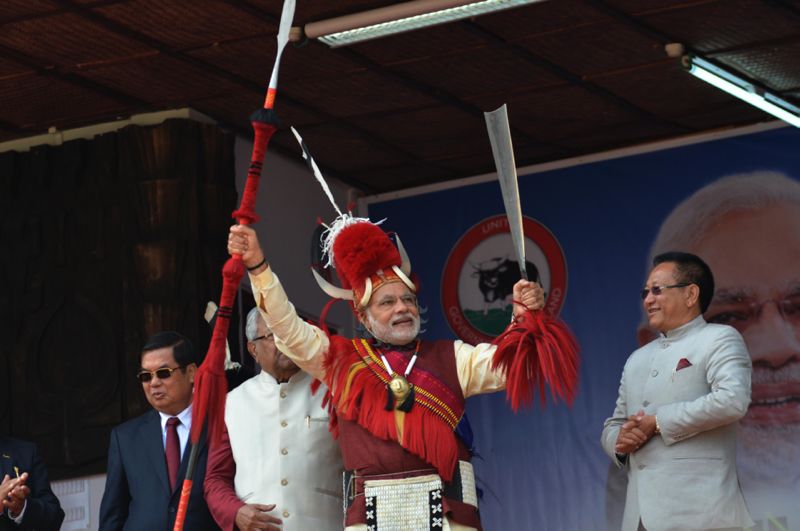

Almost six decades later, Narendra Modi, the most stringent critic of India’s first prime minister, perhaps unwittingly, emulated his bête noire’s Naga policy hoping to achieve in Kashmir what Nehru failed in Naga areas — emotional integration of people through military might.

Special status

To deal with the Nagas, Nehru, however, ultimately relied on his Kashmir model of greater autonomy as enshrined in the Article 370 of India’s Constitution. A 16-point agreement was signed with the Naga People’s Convention to create Nagaland as the 16th state of Indian Union on December 1, 1963, with special provision assured under Article 371(A). It has not only brought some degree of stability and peace in the hostile region, but also became a standard motif in dealing with minority nationalism in the country, particularly in its north-eastern region. A similar special protection has been given to Sikkim through Article 371(F) and to Mizoram through Article 371(G). Arunachal Pradesh is given special provisions under Article 371(H) while Assam and Manipur enjoy similar provisions under Article 371(B) and 371(C) respectively.

There is no denying that the statehood helped integration of Nagas with mainland India to a large extent even though insurgency remained a continuous source of violence despite several accords and peace attempts. Issues of sovereignty and integration of Naga areas left outside the territory of the nascent state, however, remained sore points.

Attempts to divide the Naga movement by signing the Shillong Accord in 1975 with a breakaway faction of the NNC, sidelining the “vanguards”, only proved counterproductive as, Nagaland plunged into another cycle of violence soon, with militants almost running a parallel government under the banner of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN), which was formed in 1980.

Even the subsequent split in the NSCN in 1988 into NSCN (Issack-Muivah) and NSCN (Khaplang) did not contain the spiraling violence. Rather, it spiked fratricidal killings.

The Shillong Accord experience is particularly relevant in today’s context as the main Naga militant group — NSCN (IM) — involved in the ongoing peace parleys with the Centre, recently hinted at the possibility of its efforts being sabotaged by others as the negotiations entered a crucial stage.

“…But, sadly, when the harvest time comes, the thieves, the animals and the birds come to the field to claim shares they have not labored for,” read a statement issued by the information and publicity wing of the NSCN(IM) on September 11.

Truce with NSCN (IM)

Another milestone in the Naga history was the signing of ceasefire agreement in 1997 by the NSCN (IM), an offshoot of the NNC which had by then grown into a major militant outfit of the region with an estimated strength of 5,000 armed cadres.

After 18 years of negotiations with five prime ministers, the NSCN (IM) leadership signed a framework agreement with the Modi government on August 3, 2015, to end what is probably the world’s oldest running insurgency. Both the negotiating parties remain tight-lipped about the content of the agreement, although they assured the Naga people that a solution was round the corner.

Since then, much water has flown down the Doyang, Dhansiri, Dikhu, Tizu and many more rivers and streams that meander through hills between upper Assam and northern Burma that form the natural habitat of more than 16 distinct tribes identified by a common nomenclature, ‘Nagas’.

Abrogation of Article 370 and introduction of new fears

The Modi-led NDA government at the Centre started its second term by trashing the very idea of providing greater autonomy to any ethnic group by abrogating the special status of Jammu and Kashmir under Article 370 of the Constitution. The ideology behind the move is to make a diverse India a unitary setup based on the RSS-BJP’s idea of ‘Ek Nishan, Ek Vidhan and Ek Pradhan’ (One constitution, one flag and one sovereign head).

According to Ao, it was only because of political exigency of the BJP that Article 371 (A) has not been tinkered with yet. “The spirit behind the provision, however, has already been trampled,” he tells The Federal over phone from his Dimapur residence.

This narrowing down of the idea of India is already rocking the ongoing peace talks between the NSCN (IM) and the Union government. The Naga militant group wants a solution, keeping with the principle of shared sovereignty. It has made it clear that a separate flag and a constitution for the Nagas are the core issues, which means they are non-negotiable.

Earlier, these demands would have been considered mere posturings by any Indian government just as Indira Gandhi had in the 1970s offered the Nagas “anything but sovereignty”. After all, the inherent flexibility of the Constitution of India allowed the state in the past to expand its framework to accommodate aspirations of self-determination of marginalised communities. Even Modi’s interlocutor in the Naga peace process RN Ravi had in March this year termed these outstanding issues as “symbolic in nature”.

But the rules of the game have since changed even as the Modi government has set a deadline to wrap up the Naga peace process by the year-end.

Emerging from its last meeting with Ravi on July 26, barely a week after former special director of the Intelligence Bureau was also appointed as the governor of Nagaland, the NSCN (IM) leadership stated that the huddle did not go well.

Later, it was known that the Centre has toughened its stand on the NSCN (IM)’s demands for a separate constitution and flag, expectedly so as the BJP’s ultra-nationalistic constituency would perceive it as dilution of national sovereignty.

“In the present context, this demand of separate flag and constitution is not pragmatic,” points out professor Xavier Mao of the North-Eastern Hill University (NEHU). In the RSS-BJP’s milieu of one homogenous India, Mao says, such a special provision has no place.

In the same breath, he adds that “give-and-take” should be the basis of any conflict resolution, suggesting that if the government did not find the Naga demands for flag and constitution concurrent with its idea of a nation-state, it should then make concessions to the Nagas in regards to bringing all Naga-inhabited areas under one administrative umbrella.

If Naga contiguous areas were integrated, he adds, then there could be some hope of a lasting solution without contradicting the BJP’s idea of homogeneity.

However, that is one Pandora’s box that even Modi, with all his tall claims of shaking the status quo, would not dare open.