- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Kallars are paying the price for a century-old crime that was never committed

By branding and constantly calling Kallars thieves, over a period of time, these people themselves started to believe that their ancestry was into robbing.

A couple of years ago, a 24-year-old from Kalappanpatti village in Madurai was picked up by the local police. His father, Mayandi (name changed), was told that the young man was detained on suspicion of robbing a couple of their jewellery while they were returning to the village after attending a marriage ceremony in the town. The father though claims that his son was held for being a member...

A couple of years ago, a 24-year-old from Kalappanpatti village in Madurai was picked up by the local police. His father, Mayandi (name changed), was told that the young man was detained on suspicion of robbing a couple of their jewellery while they were returning to the village after attending a marriage ceremony in the town.

The father though claims that his son was held for being a member of the Kallar community.

“My son had gone to the town to purchase agricultural products and was picked up by the police while returning home that night. There were many others who were coming back to the village, but the police picked up only my son. When asked about it, they [the police] called us names and said only Kallars would rob people. The police though didn’t give any evidence,” says Mayandi.

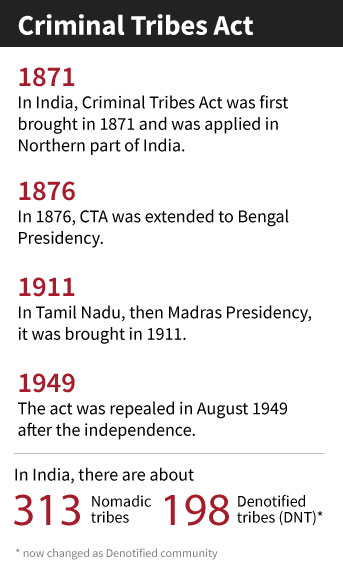

Kallars like Mayandi and his son are among nearly 150 communities across India that were labelled as “criminal tribes” by the British colonial government under the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871. It was repealed in 1949 and the communities were ‘denotified’ on August 31, 1952.

“Such random police action has been a regular affair since the social stigma attached to our caste continues to haunt us,” Mayandi laments.

- The Mukkulathor, a cluster of Kallars, Maravars and Agamudaiyars, are believed to have originated from Indra, the Hindu warrior god

- Historically, Kallars were part of the armies of Tamil kings

- Maravars and Agamudaiyars were engaged in farming

- A small group of Kallars was into guarding kings and chiefs

- When the British came, the Kallars lost their jobs as guards

- This reportedly forced them into robbing, being skilled in fighting with sticks and weapons

- Kallars are also believed to be one of the earliest Dravidian tribes

Resisting the stigma

Back in 1920, one April morning, hundreds of Kallars had gathered at Kathandamman temple near Perungamanallur village in Madurai to resist the inhuman Criminal Tribes Act brought in by the British.

Anticipating the resistance, the colonial administration had posted a battalion of police force armed with guns. The Kallar tribesmen from Kumarampatti, Alligundam, Kammalapatti and Kalappanpatti too had gathered with country-made weapons, including firecrackers, sticks, sickles and knives to face any action from the British.

When the police marched towards Perungamanallur, the protestors burst two firecrackers. Alarmed by the size of the crowd gathered at Perungamanallur, revenue officials issued a firing order and about 16 villagers, including a woman, were shot dead in the incident. According to Perungamanallur villagers, the woman, Mayakkal, had gone to the spot only to give water to the injured men in the crowd and was not part of the protest.

While 16 were shot dead, hundreds of people were arrested and dragged by iron chains to a nearby town.

“The denotified tribes continue to face the stigma and repression,” says Mayandi, who happens to be a descendant of Mayakkal.

Quest for financial well-being

A memorial of the 1920 massacre — a pillar with the names of the 16 people engraved on it stands tall in Perungamanallur. The Kallars, Maravars and Agamudaiyars, all Tamil-speaking communities, in the state are collectively called Thevar or Mukkulathor (a politically powerful OBC group).

Even though the Thevars are regarded as politically influential, the Kallars among them living in and around Perungamanallur village claim their political significance hasn’t been able to erase the stigma attached to them. “Some of our community members have managed to gain a foothold in politics and a few others made use of the government’s reclamation policy. But that hasn’t made our life easier,” says Mayandi.

It is not just Mayandi’s son who was picked up by the police and questioned in connection with a robbery case. “People from our community are often charged with goat and cow thefts,” says Mookkaiya Thevar, a resident of Perungamanallur.

Mookkaiya believes even though they are part of the Thevar community, the poor among them haven’t been able to get rid of the casteist slurs and discrimination. “We can do that only if we are economically well off,” he adds.

To be economically well off and on a par with the other caste Hindus, including the two other groups within the Mukkulathor clan — Maravars and Agamudaiyars — most of the Kallar youths choose to work in their farms. Very few opt for government jobs.

“If the Maravars own cars, so should we. If they wear jewellery to functions, we too must. It is only then that we will be respected and considered equals among the Thevars,” believes Periyannan.

The quest for ‘financial equality’ has led many villagers to take their wards out of schools and instead encourage them to help add to the family income. Although under the Kallar Reclamation Act, there are about 260 Kallar Reclamation Schools — including primary, middle, high and higher secondary schools — the number of students enrolled in the primary and middle schools has dwindled sharply in the past few years.

According to Democratic Youth Federation India (DYFI) functionary Karthik, in a recent survey by the DYFI, there were about 20 schools in and around the Usilampatti, where the strength of the students dropped below 10 and the schools were about to shut.

“We initially thought that they were admitted to private schools, but later came to know that the villagers could not ‘afford’ to send their children to schools. They instead preferred making use of the manpower in their farms,” he says.

Tamil Nadu Primary School Teachers Federation (Kallar School branch) president P Theenan from Dindigul district, however, says the enrolment in these schools has dropped not only because the parents want their children to work, but also because of the quality of education.

“There are so many teaching posts lying vacant in the Kallar Reclamation schools, which the government is not ready to fill up,” alleges Theenan. This, he says, is because most teachers just after recruitment manage to get a transfer and leave the village. “Also, while recruiting primary-level teachers, priority has to be given to candidates from the Kallar community. But the Teachers Recruitment Board hardly follows this.”

A controversy over Kallar Reclamation schools had erupted earlier after state Education Minister KA Sengottaiyan declared government plans to merge these schools with regular government schools. However, the plan was put on the backburner following objections by several Kallar outfits.

Interestingly, most of those who studied in these reclamation schools — making use of financial assistance through Kallar Reclamation Act — chose to join either the police force or the Army after completion of school. This, the villagers claim, is because of the desire to associate themselves with their ‘ancestral profession’.

“Kallars originally served as soldiers to kings and fort guards in the region. So, we either have to do farming or have to be a soldier. Also, we find it easier to land such jobs rather than getting into a professional course and waiting for a job in the cities,” says Veeranan.

From oppressed to oppressors

Even though the Kallars in Madurai are struggling financially, this doesn’t stop them from discriminating against Dalits along caste lines. It was also evident during the same DYFI survey mentioned above.

“In some villages, school dropouts mostly included Dalits. Villagers said that they took their children out of schools because of the prejudiced treatment meted out to them by the Kallars in the reclamation schools,” Karthik adds.

While the Kallar community continues to battle the century-old stigma (of belonging to a ‘criminal tribe’), which often results in persecution and unwarranted police action, it is difficult to understand what makes them discriminate against the Dalits.

A cross-section of villagers The Federal spoke to claim they do so in order to maintain their own ‘social status. “If we treat them [Dalits] equally, we will be further looked down upon by the caste Hindus as well as other groups within our own Mukkulathor clan,” says a villager who doesn’t want to be named.

An IAS officer from the community laments that the Kallars have been denied economic and social development. “Despite facing repression for no reason, Kallars are being denied their basic rights, including reservation. At least earlier Kallars were considered a Denotified Tribe and given reservation and financial assistance that were given to the Scheduled Tribes,” the officer tells The Federal on condition of anonymity.

“But after it was changed to Denotified Community (in 1979), all these benefits were pared down. Now we have to share everything with the other Backward Class people who enjoy a much better position in society.”

Last year, the state government had issued an order to restore the Denotified Tribes status to 68 communities in Tamil Nadu that were classified as Denotified Communities (DNCs) in 1979. Kallars were one of the 68 communities. But the order, many among the DNCs claim, failed to correct the anomaly.

Interestingly, according to the new order, these communities would still be called Denotified Communities in Tamil Nadu for the purpose of availing caste-based reservation in state and benefits under state welfare schemes. However, they would be called Denotified Tribes for the purpose of availing central government welfare schemes.

Notwithstanding the nomenclature, the labelling of Kallars as thieves and robbers, the officer adds, has been normalised over the years. “So much so that even the Kallars themselves started to believe that their ancestral job was to rob people or steal from them. This is not true.”