- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Menstrual cups: Why India is so uncomfortable with this bloody brilliant idea

When American actor Leona Chalmers invented the menstrual cup in the 1920s, most Indian women hadn’t even heard of disposable sanitary napkins, let alone used them. Almost a century later, more than 336 million girls, women, transgender and intersex people in India are still trying to come to terms with the idea of inserting a budget- and eco-friendly silicone cup into their body. Despite...

When American actor Leona Chalmers invented the menstrual cup in the 1920s, most Indian women hadn’t even heard of disposable sanitary napkins, let alone used them. Almost a century later, more than 336 million girls, women, transgender and intersex people in India are still trying to come to terms with the idea of inserting a budget- and eco-friendly silicone cup into their body.

Despite their long history, menstrual cups are hardly known in India, compared to the widespread acceptance and use of disposable sanitary napkins, especially in the developing countries. Made of medical-grade silicone, menstrual cups are usually reusable.

In her book, The Intimate Side of a Women’s Life, Chalmers included the first diagrammatic instructional description of how to insert menstrual cups.

These cups, ranging from ₹500 to ₹2,000, work on the radical principle of ‘collection’ of menstrual blood, instead of the standard ‘absorption’ method used in pads and tampons. Just like tampons, and unlike sanitary napkins, the cup is placed inside the vagina, where it creates a suction that holds it firmly in place. Each cup can carry 10-38 ml of blood and needs to be emptied every 4-12 hours, depending on the menstrual flow. One only has to ‘pinch’ the bottom of the bell-shaped cup to release the suction and remove it. Instead of placing a new sanitary napkin, menstrual cup users just have to empty and wash their cup before putting it back inside. There you go! No rashes, no scratches.

Women are always wary of menstrual blood leaking from pads. Advertisements of standard menstrual products almost always feature a chirpy woman, wearing white pants no less, jumping over fences as she advocates for the ‘leak-proof’ brand in question. But that’s hardly the case. Cups, on the other hand, don’t leak if inserted correctly and cause any irritation or rashes.

One can see why many women find cups an appealing option. Thara Srinivasan, a 36-year old entrepreneur, says, “If not for cramps in the first couple of days, I’d forget I’m on my period. The thought of (going back to) wearing pads or tampons just seems plain uncomfortable now.”

Empowerment and environment

Attempts at menstrual management have gone beyond urban areas, even if the cup has not. A couple of years ago, #ThePadEffect campaign started a meaningful conversation on sustainable menstruation. It was a two-fold empowerment approach for women, especially in rural areas, who now have access to cheap and good quality pads, and money-making avenues such as community-owned pad making units.

While such empowerment is long overdue, we are quietly ignoring the environmental cost of making sure every menstruating woman has access to pads. Sanitary napkins can take up to 800 years to decompose in our landfills. An average woman uses 5-8 pads per cycle and can create up to 125-150 kg of sanitary waste in her lifetime. That’s a lot of pads. The Swachh Bharat Abhiyan has failed to address the unintended consequences of increasing access to pads for our monthly needs.

Surely, then, menstrual cups should be a game-changer. So, why aren’t they more widespread?

The greatest barrier is who and what our society considers as pure or impure.

The who: virgin.

The concern of ‘losing one’s virginity’ if you use a ‘penetrative’ device such as a menstrual cup is hard to combat. Quora has multiple threads on questions such as ‘Can menstrual cups break a hymen?’ and ‘Is it safe for a virgin to use menstrual cups?’.

The concept of virginity is a prized possession in Indian families and the thought of a woman ‘inserting’ something inside her vagina, month after month, is quite scandalous in a largely conservative country like ours. Inserting a finger inside your vagina is considered taboo, let alone a seemingly large object like a cup.

The what: periods.

Culturally, periods are considered ‘impure’. Women are not allowed in certain areas of the house and are given separate clothes and utensils to use during their period days. For many, touching the blood is considered impure. While removing a pad and putting on another one doesn’t leave ‘impure’ blood on your hands, cups are a different area. Since menstrual cups are based on a ‘collection’ approach instead of an ‘absorption’ method, cup users invariably end up touching their own blood in the process of removing and inserting the cup.

Aside from taboo, concerns of Indian women range from comfort, hygiene and pain to the mess it may create. Cups are not readily available in local shops, and there’s a steep learning curve. Finding the correct size is often a challenge for many first-time users.

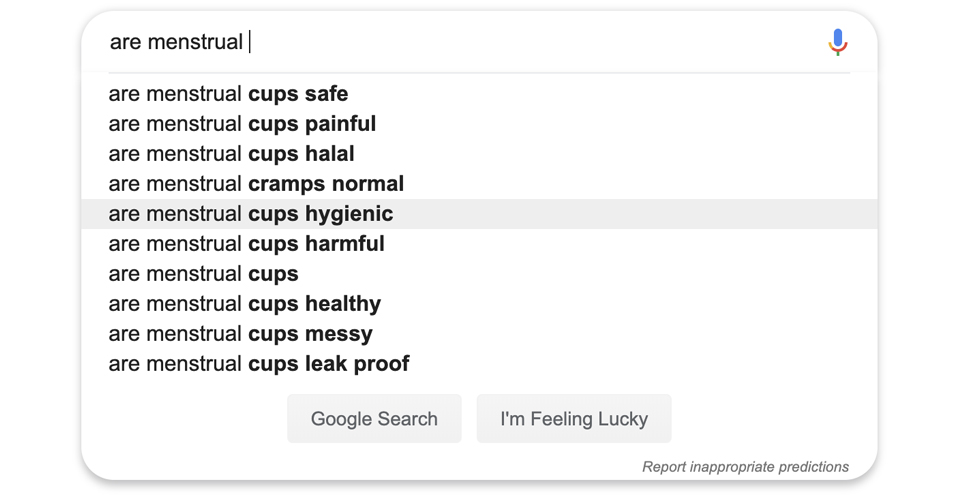

Google shows a glimpse of the common fears:

One of the biggest concerns include the fear of inserting a ‘foreign’ object in the body. Devika Kapoor, a 25-year-old psychologist in Mumbai, overcame her fears while switching to the cup early this year. “It wasn’t about any social taboos for me. I was just scared of penetrative objects,” she says. Such a fear is not without reason. Sanitary napkins are always on the outside, unlike tampons and cups, which are placed inside your vagina.

Nayonika Roy, a 24-year old project officer for SoCh for Social Change from Hyderabad, is an advocate for menstrual cups. “I recommend (cups) to every other person I meet. Reactions range from the discomfort of seeing blood to discomfort in inserting fingers into the vagina,” she says.

Lack of water and access to safe bathrooms are significant barriers for women to switch to cups. Perhaps that is why many cup users are predominantly urban middle-class women who have 24/7 water supply and easy access to clean bathrooms.

Several firms are lining up sustainable products for menstruation. It’s largely a women movement for women.

Still, these urban women have found cups to be greatly ‘empowering’. Naturally, one wonders if we can uplift rural women too by making them adopt cups over napkins. Apart from this being an isolated beneficiary based thinking, we are entirely erasing rural women’s choice to use cloth as an effective medium for menstrual management. Notwithstanding the concerns of using a cloth (mainly hygiene based), we assume that women who use cloth instead of napkins are ‘oppressed’. That’s not always the case.

‘Date Batte’, used in rural Karnataka, is red coloured soft cloth available at local grocery stores. Women here, by large, do not wish to shift to pads because their current method is extremely comfortable.

But, of course, we must see the usage of cloth for menstrual management in its broader context. In a research study called ‘Menstrual cup use, leakage, acceptability, safety, and availability’, published in The Lancet, the authors of what might be the first-ever study on menstrual cups, highlight how single-use products are preferred choice for many agencies. Menstrual cups are lesser known as an alternative in ‘resource-poor settings.’

Advertisements have a considerable role to play in increasing the adoption of menstrual cups. It was radical when actor Courtney Cox of ‘Friends’ fame featured in a commercial for tampons.

Why haven’t we seen any radical ads on menstrual cups? Because almost all makers and suppliers of menstrual cups are social entrepreneurs and start-ups. Unlike profitable multinational companies, these organisations rely heavily on digital medium to promote their products. Naturally, urban women are the first consumers.

Sirona Cup has recently released, perhaps for the first time in India, an advertisement on menstrual cups. Featuring social media influencer and actor Shibani Bedi, this wholesome ad talks about the problems of using pads and how cups are the solution to all of our collective period woes.

In the ad, Bedi touched upon a part of the reason why women take a long time to try cups. We follow the practices laid down by our mothers and their mothers.

This is a stark contrast to how most cup users are introduced to the product — by their friends, offline or online. Thirty five-year-old Suman (name changed) from Chennai first heard about menstrual cups back in 2016 through an online parenting group on Facebook.

Twenty five-year-old anthropologist Akshatha Nayak, based in Udupi, first heard about menstrual cups in 2010, when she was searching online for alternatives to sanitary napkins. She bought her first cup in 2015, only to give up after being unable to insert it properly. Like many others, she too relied on the collective wisdom of long-time cup users to get through the learning curve. Akshatha joined the Facebook group Sustainable Menstruation India and found support to help her move past her challenges. She’s been a happy cup user since 2017.

She believes that many women are now educated about cups and are more likely to try it. Hearing positive reviews from friends has been an effective way to get past fears.

The study published in The Lancet recommends that information on cups must be included in educational materials and menstrual health programmes. Until we make sustainable changes in the way we approach menstruation in India, the cup will, unfortunately, remain what it is now — an alternative.

Challenges and steep learning curve aside, menstrual cups are the safest and the best option till date. Period.