- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

It’s a novel, it’s a play, now a film – the many legends of Ponniyin Selvan

When Tamil writer-journalist Kalki Krishnamurthy set out to write a historical fiction, little did he know that Ponniyin Selvan would change the course of history of Tamil literature. Or, maybe he did. For, many of his readers still believe the epic novel – spread in five volumes running over more than 2,000 pages – is a true account of the history of the Chola dynasty. The...

When Tamil writer-journalist Kalki Krishnamurthy set out to write a historical fiction, little did he know that Ponniyin Selvan would change the course of history of Tamil literature. Or, maybe he did. For, many of his readers still believe the epic novel – spread in five volumes running over more than 2,000 pages – is a true account of the history of the Chola dynasty.

The historical fiction, Ponniyin Selvan, is a vivid depiction of the mighty Cholas, particularly the medieval (848 CE to 1010 CE) and the later Cholas (1070 CE to 1279 CE), which captures the landscape and culture of the times with a realistic touch.

The Cholas of southern India were one of the longest-ruling dynasties — between 300 BCE and 1279 CE — in world history. Historians claim that the Cholas laid the foundations for modern public administration and theirs was a golden period in the history of Tamil Nadu. The Cholas also took care to document their history and achievements by building temples with a lot of stone inscriptions. Huge stocks of copper plates dating back to the Chola period are also rich in inscriptions dishing out details of the lives and times of the Chola dynasty. That is also possibly the reason why literature related to Tamil Nadu history often has a large number of references to the Cholas.

Given the rich wealth of history, many historians such as KA Nilakanta Sastri, Tamil scholars like Ma Rasamanikkanar and writers such as Sandilyan and Balakumaran produced seminal works on the Chola dynasty. No wonder then Krishnamurthy was also fascinated by it and penned Ponniyin Selvan.

The novel was first serialised in a magazine Kalki Krishnamurthy ran under his first name between October 29, 1950, and May 16, 1954. It was received well and owning the hardbound volumes of the series was seen as a matter of pride at the time. The five-volume book has taken many forms over the years. It has been adapted on stage, turned into audio books, an animation film and comics. On September 30, it will be released in the form of a film directed by Mani Ratnam with an ensemble cast of Vikram, Aishwarya Rai Bachchan, Jayam Ravi, Karthi, Trisha, Aishwarya Lekshmi, Sobhita Dhulipala and Prabhu among others.

Ahead of the movie’s release, The Federal tried to track the story of the adaptation of Ponniyin Selvan to theatre by Chennai-based Magic Lantern in 1999. This in itself is an epic story of camaraderie among various artistes and theatre groups to overcome challenges.

Looking for a successor

The novel, Ponniyin Selvan, basically revolves around the hunt for a worthy successor to run the empire. After Parantaka Chola’s death, his younger son Gandaradithan takes over the reins because the elder son, Rajadithan, dies in a battle. A few years later, Gandaradithan also dies in a war, leaving behind a two-year-old son Madurantaka. This leads to a major succession crisis. So, instead of Madurantaka, Gandaradithan’s younger brother Arinjaya comes to power. After Arinjaya’s death, his son Sundara Chola gets the throne. But when Sundara Cholan turns old and is bedridden, a discussion ensues again on the rightful successor.

While Sundara Cholan is blessed with two sons Aditha Karikalan and Arulmozhi Varman, Gandaradithan’s son Madurantaka by the time is old enough to claim the throne and joins the race. While some of the smaller chieftains, who were close to Sundara Cholan, want either Aditha Karikalan or Arulmozhi Varman as the successor to the king, others close to Gandaradithan believe Madurantaka to be the rightful successor.

Even as the discussions and debates over the successor go on, Aditha Karikalan gets killed by unknown people. What happens next forms the rest of the plot which has 55 characters with some memorable ones such as Vandhiya Devan, Kundavai, Azhwarkadiyaan, Periya Pazhuvettaraiyar, Nandhini, Poonguzhali and Senthan Amuthan.

Kalki’s writing style was so vivid that many people even today tend to believe that the novel is a historical account of the Chola kingdom. It had all the elements – romance, action, comedy and emotions – that make a good cinema.

Back in the day, when the Tamil film industry was mostly churning out mythological and historical films, yesteryear superstar MG Ramachandran tried to adapt the novel to screen. But for reasons unknown, the project never took off. Similarly, next generation actor Kamal Haasan also tried to adapt the novel onscreen but eventually gave up. Mani Ratnam himself attempted to make the film in the 1990s, but budget proved to be a constraint. Shankar, another filmmaker in the Tamil industry who is known for onscreen grandeur, expressed a desire to turn the novel into a film. He too didn’t succeed.

Now that Mani Ratnam is finally ready with a film based on Kalki’s novel, as expected, it has generated a lot of interest among people. Even the Tamil Nadu Tourism Development Corporation (TTDC) has decided to cash in on the Ponniyin Selvan fever. Ahead of the film’s release, the TTDC has come up with a three-day tour package called ‘Ponniyin Selvan trail’. The tour aims to explore places where Ponniyin Selvan events took place, in the land of the Cholas.

Bringing the Cholas on stage

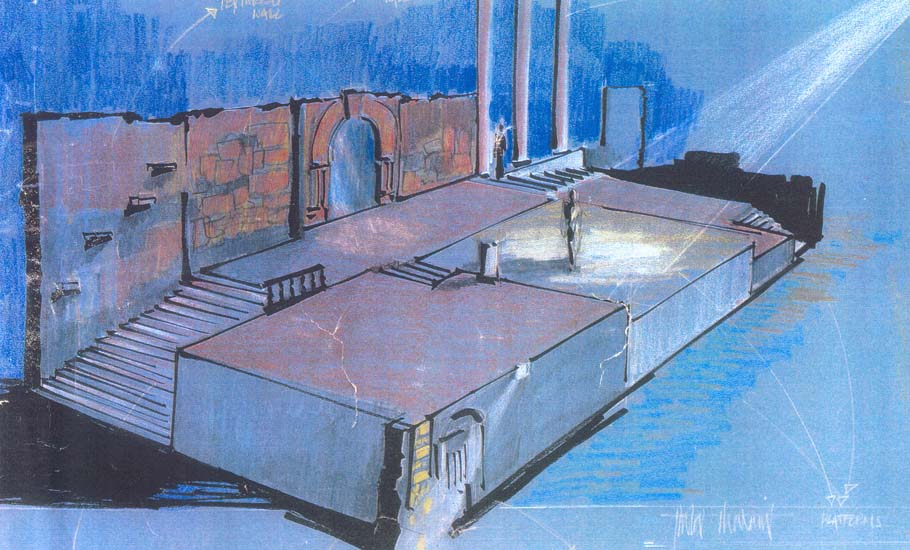

“Ponniyin Selvan was first staged in 1999 at the amphitheatre in YMCA, Nandanam, Chennai. Although this was a Magic Lantern production, it was a collaboration of various theatre organisations, film technicians, academicians, cultural organisations, actors, and Kalki fans,” Pravin Kannanur, one of the cofounders of Magic Lantern and the director of Ponniyin Selvan, told The Federal.

“In 1990, I came to Chennai after undergoing training at Strasbourg School of Theatre in France for one year. Along with my friends like actors Pasupathy and Jayakumar in Koothu-P-Pattarai, I worked on many plays. With funding from the French embassy, we staged French playwright Moliere’s Don Juan. Then we staged Albert Camus’s Caligula. In 1992, I, along with Hans Kaushik and E Kumaravel, co-founded the Magic Lantern,” he said.

“Once while we were staging Veshakkaran in one of the villages named Akhoor, film scholar and currently professor at Michigan State University, Swarnavel Eswaran, was also in the audience. After the performance, he asked why we don’t adapt Tamil literary works like Ponniyin Selvan to the stage. That’s how the idea of adapting the novel came to us,” Pravin shared.

While Kumaravel took care of the writing process, Pasupathy trained the actors in physical and martial arts, and choreography. Academician Punithavathi Elangovan was entrusted with the responsibility of teaching language nuances to the actors. The core team of the play also met historian Kalaikovan for an understanding of the Chola kingdom and some readers of the novel to get a sense of their idea of the novel’s characters.

“We started working on the play in September 1998 and spent six months practicing and rehearsing. Rehearsals require a huge space. So, we sought the help of Na Muthusamy [founder of Koothu-P-Pattarai] to provide us a space. He was generous to the extent that he stopped all his productions for those six months so that we could use the space. He also gave us some of his actors for the play. In order to raise funds for the production, we staged some five-six scenes from the novel in Chennai. As an add on, we got 32 review articles in major publications praising our work,” said Pravin.

The publicity brought people from different walks of life to join this effort. Art director Thotta Tharani, who is handling the direction of Ponniyin Selvan (film), did the stage background work. Many theatre groups such as Marapachi run by A Mangai, Gnani’s Pareeksha, KA Gunasekaran’s Thannane became a part of this project.

Actor Nasser provided wigs and weapons such as swords from his collections. Actor Mariam George, a much sought-after comedian now, took the narration work. Well-known photographer G Venkatram did photography for publicity materials. Filmmaker Rajiv Menon supported the group with a soundproof power generator so that the dialogues could be heard clearly. “All these people contributed free of cost,” Pravin told The Federal.

“The running time of the play was 4.5 hours. The length of the stage was 120 feet. For an actor, even to enter and exit the stage would take at least a minute. If we gave 15 minutes intermission, the time of the play would have extended further. So, we didn’t have any breaks. Our actors sacrificed their time, family and even their own health for the play.”

Pravin goes on to narrate an instance when one of the actors, Lawrence, who played the character of Chinna Pazhuvettaraiyar, was required to jump from a height of 14 feet in one of the scenes. “During the time of rehearsal, he was down with typhoid. But he didn’t tell us that. Every night after the rehearsal, he would go to the hospital and get IV [intravenous] drips.”

The play became such a huge success that it was staged again in 2014 and 2017 by SS International Live.

“In the 1980s and the 1990s, contemporary Tamil theatre basically followed lyrical tradition, which means the plays had more songs, whereas Parsi and English theatre were more about dialogues. It was during that time we staged Ponniyin Selvan which had songs, dance and action sequences. It was received well by the audience,” Pravin said.

‘Fiction, not history’

Talking to The Federal, scriptwriter-actor E Kumaravel aka Elango Kumaravel, one of the founders of Magic Lantern who has now worked with Mani Ratnam on the film’s script and screenplay, said the writing process was never difficult but adapting the writing to stage was.

“The writing took six months. The novel’s plot is simple, ‘Who will be the next king?’. I wrote the script that has a ‘five-act structure’ [a formula that divides the story into five parts like exposition, rising action, climax, falling action and resolution]. Theatre is a visual medium. It is the execution, that is, acting is adaptation, not the writing part. Our actors understood that and acted accordingly. They at least know what they should not do on the stage. That became one of the reasons for the success of the play,” he said.

Kumaravel, by assisting his father Ma Ra Elangovan, a journalist, in his research activities, developed the habit of reading at a young age. In his student days, he got introduced to Ponniyin Selvan. After completing his formal training in theatre at Pondicherry University’s Sankaradas Swamigal School of Drama under the aegis of Indira Parthasarathy, a renowned writer and dramatist, Kumaravel was in Koothu-P-Pattarai for eight years. While simultaneously working in theatre, he also continued to act in movies.

When the team started working on this project, they kept three types of audience in mind — first-time audience experiencing a stage play, another set of audience who would say that this could be their last play they are seeing, and the readers of the novel.

“While the first two sets of audience receive the play as it is, the third set tries to find faults. This is because most of the readers believe that what Kalki wrote was true history. Of course, Kalki has taken some real life characters and incidents to weave a plot. But that doesn’t mean Ponniyin Selvan is history. It’s just historical fiction. If the readers understand this, they can enjoy both the play and the film,” Kumaravel told The Federal.

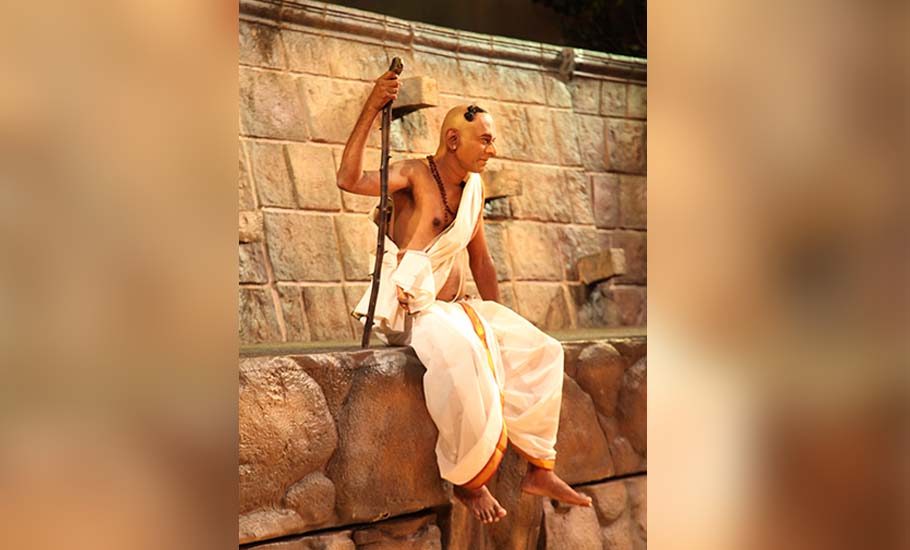

“For example, there is no detail found about Vandhiya Devan, one of the lead characters of the novel, in Chola history except a single line that he was the husband of Kundhavai, the Chola princess. Similarly, in our play the character Periya Pazhuvettaraiyar was played by Mu Ramasamy with a bald head. But in the paintings of Maniam, who drew images for the Ponniyin Selvan serial, the character was seen with a lot of hair. Interestingly, most never questioned that because the actor had embellished his character with his acting skills and the audience forgot if Pazhuvettaraiyar had hair or not. However, when the stills of Ponniyin Selvan released, many raised questions comparing the images with Maniam’s paintings. When readers mistake historical fiction for history itself, such questions will arise,” Kumaravel said.

Adapting a novel to the stage does not just mean captivating the audience but taking the audience along with you. On screen, one can go to real places and shoot the scenes, but on stage, we have to create a world. And that is the beauty of theatre, Kumaravel added.

While Ponniyin Selvan received a lot of love on stage, whether the same adulation will be showered on Mani Ratnam’s upcoming film will be known only on September 30.