- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Is a caste-riddled India ready to look beyond surnames?

Chandan Saroj, 32, a native of Azamgarh in Uttar Pradesh, holds two master’s degrees—in Sociology and Philosophy and a bachelor of education (BEd) degree. When he appeared in an interview for the post of an assistant professor in UP’s Higher Education Services Commission, he was surprised when the interviewers asked him about his beliefs on religion, what he thought of the...

Chandan Saroj, 32, a native of Azamgarh in Uttar Pradesh, holds two master’s degrees—in Sociology and Philosophy and a bachelor of education (BEd) degree.

When he appeared in an interview for the post of an assistant professor in UP’s Higher Education Services Commission, he was surprised when the interviewers asked him about his beliefs on religion, what he thought of the caste system and how many castes there were in India.

Initially, Saroj thought these questions were related to his domain as he was a sociology student. But as the interviewers went on to ask his full name, where he hailed from and whether he would rebel against the system if there’s injustice against certain caste groups, he not only got offended but also intimidated.

Saroj, a Dalit student belonging to the Pasi community, says people in UP often ask the surname to judge and value one’s achievements. Saroj feels although he had cleared the written test, his caste and surname seem to have acted as a baggage for the interviewers.

After the interview, Saroj never heard from the commission. Although he says he excelled in academics, he thinks he lost the job because he was a Dalit and his surname may have revealed the caste he belonged to.

“In my community, a lot of people keep Saroj as their second name. So one can easily recognise what caste I belonged to. But that should not be a criterion for my job selection,” he says. “Why can’t we get away with surnames in job interviews and in civil service exams. Can’t the interviewer go by one’s application number and not full name?” he asks.

Saroj is not the only one who has faced such a scenario. Brijesh Kumar, 29, an MA, BEd, from Uttar Pradesh, had a similar experience at the UP Public Service Commission (UPPSC) exam. He could not get a UPPSC job and ended up as a primary school teacher.

“Had I got a job through the public service commission, I would have been able to bring a change in people’s lives in a wider region,” Kumar says. Nevertheless, he has accepted what he got.

All in a name

Several job aspirants and students belonging to SC, ST and backward class communities often complain that their surnames are a deterrent for them.

Caste-revealing surnames result in ostracisation of Dalits and exclusion from certain jobs, education, businesses, temple entry, help from police among other things, owing to the prejudice many carry.

There are several instances of caste Hindus in Tamil Nadu humiliating Dalits bearing caste names such as Pallars, Paraiyars, Sakkiliars, among others. Casteist comments are made to discriminate against certain communities and perpetuate stereotypes.

To access mainstream society, some change their surnames.

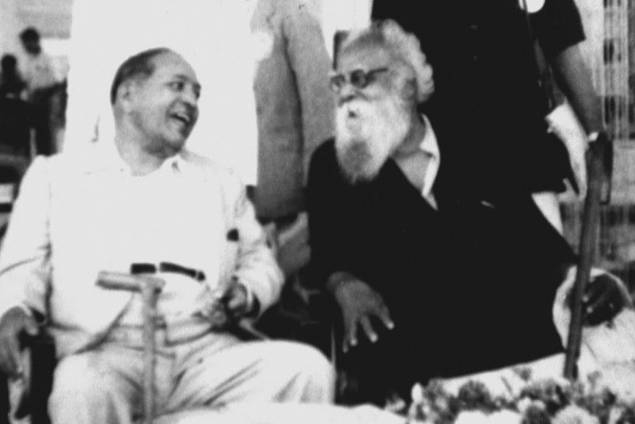

Notably, In Tamil Nadu, after self-respect rights leader Periyar dropped his caste surname ‘Naicker’ from his original name EV Ramasamy in 1929, the culture of dropping caste surnames spread in Tamil Nadu.

Several people who followed Periyar’s ideology, followed suit. Today, it’s difficult to guess a political leader’s caste as many do not carry caste as surnames.

Upper caste people including Brahmins too dropped caste implying surnames. Many took to the practice of using initials of the head of the family member or carried names of their village or place where they hailed from.

The practice is prevalent across India, though it is gaining acceptance in the north only recently.

Narendra Jadhav, a nominated Rajya Sabha member, has long been advocating people to drop surnames. He’s even proposed to bring a bill to drop caste implying surnames.

In recent days, Malayalam actor Suresh Gopi dropped Nair from his surname to set an example.

Considering that several communities in Kerala traditionally do not use their surnames, the Kerala High Court asked the CBSE to consider providing an additional column in the registration form of classes 9 and 11 for providing the full name of initials of father, mother and guardians and not force people to fill in the surname section.

The case with the govt

In February 2021, the Dalit Chamber of Commerce in India and Industries (DICCI), an association that promotes business enterprises for Dalits, submitted a draft report to the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, seeking their response to the demand that caste surnames or details of religious or social background of candidates should not be revealed at the interview stage in civil services and government job-related exams. The report was prepared to understand the progress of Dalits since Independence.

Ravi Kumar Narra of DICCI says the report was prepared to highlight the discrimination seen at the stage of personality tests and interviews in government jobs, both at the Centre and states.

“We have sent them a report seeking their response. But so far they haven’t replied yet,” Narra says.

Narra did not want the report to be made public until they got a response from the government.

It is not just Dalits and OBCs who have caste names as surnames, even upper caste people use surnames.

“While it acts against us, the same works in favour of the upper caste people as the interviewer tends to carry a different perception about their candidature,” says Saroj.

The draft report accessed by The Print, indicates that despite reservation, seats reserved for SCs, STs and OBCs in government jobs and education haven’t been duly filled.

“It took 40 years to fill 50% of the ‘Group A’ reserved vacancies and 30 years for ‘Group B’,” The Print quoted from the report. In ‘Group C’, it took 45 years to reach full scale of reservation.” It also said Scheduled Castes have lost 3,18,969 jobs due to privatisation.

Although the Constitution provides equal rights to all citizens, oppressed communities have often been ignored and despite reservation benefits, various governments have failed to give requisite representation and continued with graded inequality. And even in jobs, say in group C and D categories, Scheduled Caste people are unfairly distributed.

Some, who are politically empowered, took to fighting the system by changing their names. For instance, Chandrashekar Azad of the Bhim Army in UP calls himself Ravan.

In Telangana, some communities are using “Swaero” as their surname to move away from regular names like Harijan, Baduga and others. SW to indicate social welfare and ‘aero’, meaning sky, to say that sky’s the limit.

“To an extent, we can all fight. And some students continue to fight the system deviating from the main purpose of life, attaining excellence in education and job. In the end, they get branded as rebels and will be looked at differently by others,” Vikash Anand, a student at Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, says.

Following his harrowing experience, Saroj initially joined a private institution in Kanpur that offered him a salary in the range of ₹3,000-5,000. But after some time, he joined a PhD programme in Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi Vishwavidyalaya, Wardha, where he got a scholarship of ₹8,000 per month.

Coming from a Dalit social background, his efforts into getting his degrees were double to that of those from the ‘privileged’ castes. But even after being well qualified, not getting a job he’s eligible for is obviously frustrating.

One’s caste should never be a judging factor, Saroj says.

That, of course, is far from the reality of everyday life in India.