- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

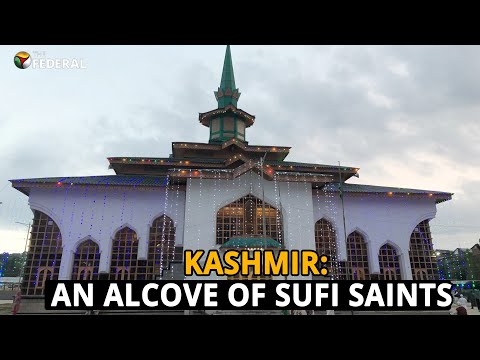

Inside a Kashmir that is also an alcove of Sufi saints

A profound verse by Lal Ded, a well-known Kashmiri Sufi mystic poetess of the 14th century, defines the Sufi conviction in her vaakh (verse): Shiv chhui thali thali rozaan Mo zaan hyond te musalman [Do not distinguish between a Hindu and a Muslim. For, he (Shiv, the creator), who created them all, is watching you ubiquitously.] There is a reason Kashmir is referred to as an alcove of...

A profound verse by Lal Ded, a well-known Kashmiri Sufi mystic poetess of the 14th century, defines the Sufi conviction in her vaakh (verse):

Shiv chhui thali thali rozaan

Mo zaan hyond te musalman

[Do not distinguish between a Hindu and a Muslim.

For, he (Shiv, the creator), who created them all, is watching you ubiquitously.]

There is a reason Kashmir is referred to as an alcove of Sufi Saints. In local parlance, Kashmir is called Pir Vaer or Resh Vaer. Sacred shrines of saints dotting every nook and cranny of the Kashmir Valley besides being architectural marvels also provide an irrefutable evidence of Kashmir’s past that is packed with tales of tragedies and triumphs.

The region of Kashmir has witnessed three major religions gaining dominance throughout its history. There are accounts of conflict as well as confluence among Buddhism, Islam and Hinduism.

Noted historian and legal luminary Abdul Ghafoor Noorani is of the view that “In the entire subcontinent, Jammu and Kashmir has the richest reservoir of the Sufi tradition, a tradition which is an integral part of the people’s ethos and which informs their lives.”

But what is Sufism? How has Sufism shaped Kashmir? Who can be described a Sufi? What are the important Sufi practices and beliefs? And what do these mean to Kashmir and Kashmiris?

Scholars define Sufism as a form of Islamic mysticism that started developing in the 7th century. Some argue that “Sufism dates back to the time of the Prophet of Islam”, and it has been present in Muslim societies for more than 12 centuries.” The term Sufi (in Arabic refers to a ‘man of wool’) was coined around the 9th century to describe mystics, wearing long woollen cloaks.

In public perception, Sufis are mystic men and women who renounce the materialistic world. They are on a mission to discover God within. A true Sufi is a person on a pilgrimage or journey that consists of seven stages: Renunciation, repentance, patience, hardship, abstinence, complete faith and trust in God, and submission before the ultimate will of God.

In its essence, Sufism is the colour blind humanism and selfless love for fellow beings irrespective of their caste, creed, and colour of skin, faith, ethnicity or nationality. It is also a belief system that sees humans as humans while indefatigably working to become a better version of oneself.

“Sufism represents the inward-looking, mystical dimension of Islam. Often thought erroneously to be its own sect or denomination—such as Sunni Islam—Sufism is better understood as an approach that mixes mainstream religious observances, such as prescribed daily prayers, with a range of supplementary spiritual practices like the ritual chanting of God’s attributes (zhikr or dhikr) or the veneration of saints,” according to Pew Research Center.

In the case of Kashmir, scholarly works produced by the late Dr Mohammad Ishaq Khan, former Dean at University of Kashmir’s Faculty of Arts, Mohammad Ashraf Wani, former head of the Department of History, University of Kashmir, and Khalid Bashir Ahmad, a former civil servant and noted author, dispel the fog over the facts in relation to the transformation of Kashmir during the 14th-15th century AD.

So, how did Sufism reach Kashmir?

‘Bulbul Shah’

The first Sufi Muslim saint from Central Asia to have travelled to Kashmir is said to be Hazrat Syed Sharif-ud-Din Abdur Rehman, popularly known to the native Kashmiris as ‘Bulbul Shah Saeb’. The Srinagar-based cultural commentator and satirist-poet Zareef Ahmad Zareef tells The Federal that Sufi Abdur Rehman became popular as ‘Bulbul Shah’. “He arrived in Kashmir during the reign of the Buddhist ruler, Ranchan Shah (Rinchana). Abdur Rehman – believed to have travelled all the way from Turkistan – settled in Kashmir roughly around 1324 AD (725 A.H).”

A shrine in Bulbul Shah’s name is located in Srinagar at a place called Bulbul Langar (now Bulbul Lankar). An interesting myth about the saint goes like this: More often the saint would be engrossed in meditation so much so that a nightingale (bulbul) would sit on his head, undisturbed. This is perhaps why the saint came to be called ‘Bulbul Shah’, Zareef added.

One of the popular mythological accounts says that the earliest people of the land (Kashmir) were known as Nagas (snake worshippers). Historians record that Buddhism gained ascendancy and remained the leading religion of the region for more than a millennium followed by Hindusim till the 12th century AD. The dominance of Hinduism, according to author and historian Khalid Bashir Ahmad, “dominated the scene through its indigenous form Shaivism. However, by the 12th century AD, it was on decline due to rampant corrupt practices by its followers. By then, Islamic influence had made inroads into the otherwise landlocked country”.

Ahmad adds: “By the 14th century, Muslim preachers from Central Asia were also attracted to Kashmir. They gradually earned mass conversion of local people to Islam. Notably, one of the earliest converts was the ruler of the day himself—Rinchana.”

‘Shah-e-Hamdan’ Mir Syed Ali Hamadani

Many saints have arrived in Kashmir to preach and to propagate Islam. They include Syed Sharif-ud-Din Abdur Rehman, Syed Hussain Samnani, Syed Taj-ud-Din and Syed Jalal-ud-Din Bukhari besides many others. “The most influential saint to have travelled from Iran’s Hamadan to Kashmir is none other than Hazrat Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani, popularly known by his honorary titles such as ‘Amir-e-Kabir’, ‘Shah-e-Hamadan’ and ‘Ali Sa’ani’ etc.,” Kashmir’s well-known preacher Showkat Hussain Keng tells The Federal.

According to Keng, ‘Ameer-e-Kabeer’ Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani was a scholar, poet and saint of the Kubrawiya order who came to Kashmir along with his spiritual companions and disciples. “He came along with his 700 companions known as Saadat (Sayyids or Syeds who trace their lineage to the family of Prophet of Islam). Ameer-e-Kabeer transformed Kashmir in multiple ways.” Keng adds: “Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani’s Saadats (700 companions) trained people in various arts and crafts, which include shawl weaving, cloth weaving, pottery and calligraphy. It was because of the saint that Kashmir became a prototype of Iran (Iran-e-Sagheer).”

During his lifetime Ali Hamadani visited Kashmir at least thrice. Born in Iran as Ali in 1313 or 1314 AD to an educated and well-respected family, Ali Hamadani was quick to learn Quranic teachings and receive spiritual training under the guidance of his maternal uncle Hazrat Ala-ud-Din. The saint passed away in a place called Hazara at Pakhli (now in Pakistan) but, as per the saint’s will, his body was laid to rest at Kolab in Tajikistan.

Ali Hamadani represented the Kubrawiya Sufi order or Silsila. There are many Sufi orders which include Qadiriyya, Kubrawiya, Suharwardy, and Naqshbandi etc.

On the other hand, another influential saint Abdul Qadir Jilani, popularly called ‘Gous-ul-Azam’ or ‘Dastgeer Sahib’, never visited Kashmir. A shrine built in the memory of Abdul Qadir Gilani or Jilani, a revered saint and scholar from Iran’s Gilan province, is situated in Srinagar’s Khanyar area. Jilani’s is Qadiriyya Silsila.

Nund Reshi

A saint by the name Sheikh Noor-ud-Din Noorani aka Nund Reshi is widely admired in Kashmir. The Sheikh is also known by the honorary title ‘Alamdar-e-Kashmir’. People belonging to various faiths, including Kashmiri Pandits, revere Nund Reshi. Muslims lovingly call the saint as Sheikh-ul-Alam while Pandits refer to him as Nund Laal or Nund Reshi.

Sheikh Noor-ud-Din was born in 1375 AD in Qaimoh hamlet in south Kashmir’s Kulgam district. His short poetic verses, known as Shrueik, are quoted by the young and elderly alike. More than 700 years ago, the saint cared about the environment and climate change. Sample this: Ann poshe telli, yelli wann poshe (food will be obtainable only when forests are preserved). His final resting place is in Chrar-e-Shareef area in central Kashmir’s Budgam district.

There are many legends that shed light on the spiritual association between Nund Reshi and Lal Ded. They were contemporaries. Ded was born before Reshi, though. As a Sufi, preacher and mystic poet, Sheikh-ul-Alam wields remarkable influence on the Kashmiri psyche besides being one of the symbols of cultural confluence between Muslims and Pandits. The saint spent about 12 years in different caves for spiritual contemplation.

Experts argue that Kashmiri poetry is incomplete without crediting Nund Reshi for his contribution in a special poetic genre – Shrueik. According to one of the legends, Noor-ud-Din, as an infant, would not drink milk from his mother’s breasts and it was only due to Ded’s intervention that the former consented to be breastfed. Lal Ded is supposed to have said this to the child (Nund Reshi): Che maali che, zen yeli ne mandchoakh, chene kath chukh mandchan? (Drink, hey drink (milk), when you were not embarrassed to take birth, why this shyness while you are being breastfed?)

Some credit Nund Reshi for explaining the essence of Quranic teachings through his effortless poetic verses.

Lal Ded

Also known as Lalleshwari and Lalla Arifa, this Kashmiri mystic merged spiritual longing in her poetry. Born around 1320 AD, Lal Ded became famous for her vaakh (verses, sayings). It is said that her mother-in-law treated her with contempt and cruelty. During early mornings she would cross a nearby river for her spiritual reflections, but her mother-in-law, noticing her long absences, suspected her of infidelity. Both Islamic scholars and Hindu chroniclers own her and record the saint’s encounters with their revered personalities. Kashmiris of all faiths religiously quote Lal Ded’s vaakh and Sheikh-ul-Alam’s shrueik during conversations.

Faith is the healer

Inside many shrines in Kashmir, devotees (women, men and children) can be seen chanting Naatiya Kalam, Manqabat and Khatmaat in Persian, Arabic, Urdu and Kashmiri languages. People belonging to different faiths are present at shrines like Sheikh-ul-Alam’s at Chrar-e-Shareef and Dastgeer Sahib’s in Srinagar.

Most Kashmiris do not feel comfortable with the puritanical practices that dominate the scene in the Middle East. That is perhaps why no one could thrust upon them orthodox lifestyle. Early years of armed militancy in the 1990s were, therefore, frustrating for the people of Kashmir. On the one hand, government soldiers would humiliate common people in the name of frisking, ordering them to get down from the local buses for identification parade and make them walk long distances before they could take their respective seats in the buses again. Elderly people, too, were not spared.

On the other hand, some armed militants would conduct their own random checks in public buses and private vehicles to ensure that women had put on veils or covered their faces adequately with scarves or burqas. The militant groups that were trying to enforce a particular dress code for women soon retracted from such undemocratic practices because of the lack of social acceptability and social sanction for the same.

According to one of Kashmir’s leading psychiatrists, “In Kashmir, faith (aqeeda) is the real doctor.” This aqeeda unites people. Before 1989, women from the Kashmiri Muslim and Kashmiri Pandit communities would visit the shrines together. Before the outbreak of a deadly conflict, there were many spaces like Srinagar downtown’s waane pyaend (shopfront) which would act both as intellectual and cathartic space during the continued battle for existence and identity. The practice of visiting shrines in Kashmir has actually been a liberating, cathartic and therapeutic exercise for many.

The Sufi beliefs and practices remain a vital part of the lives of the people living in Kashmir. At various shrines one witnesses large crowds during the annual Urs gatherings. Many Kashmiri women are shrine-goers. During Urs, devotees in numbers could be seen tying votive threads on the decorated windows near the mausoleums, some planting kisses over the outside walls of the saint’s burial place, and even rubbing the walls with their right hand and then dabbing the blessing onto their faces with conviction and faith.

Earlier, women would also visit yarbals (ghats) where they would wash their clothes and talk. And many Kashmiri families would visit famous alcoves of almonds like Badamwari in Srinagar to spend time with their spouses, kids, parents and grandparents. Shrines dedicated to revered saints are an intrinsic part of Kashmir’s culture, social fabric and vibrant tradition of harmony.