- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Zia Hind! The irony of calling Faiz’s poetry anti-Hindu

The late Pakistani dictator General Zia ul-Haq would be so proud of Indians. All his life he wanted to ban Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s poetry, calling it anti-national, anti-Islamic, and almost anti-everything. General Zia failed miserably. But he would be ecstatic his ideological scions in India have taken up the challenge of banning the poet’s work, branding it anti-Hindu. We can already hear...

The late Pakistani dictator General Zia ul-Haq would be so proud of Indians. All his life he wanted to ban Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s poetry, calling it anti-national, anti-Islamic, and almost anti-everything.

General Zia failed miserably. But he would be ecstatic his ideological scions in India have taken up the challenge of banning the poet’s work, branding it anti-Hindu. We can already hear the late dictator trying to scream (more about it later) in his grave (which, as if in deference to Faiz’s iconic poem Hum Dekhenge, doesn’t exist): “Zia Hind!”

The poetry of Faiz has always inspired rebels and humanitarians because of its stirring anti-establishment sentiments and lines that read like war cries. For decades, his revolutionary couplets have acted as rallying calls for people to rise against oppression, tyranny and injustice. Naturally, his words have scared dictators, despots and authoritarian regimes.

Book burning isn’t a typical Nazi trait. All despots, bigots and fascists are really scared of new ideas and the written word, even though they themselves love writing them. They are afraid that independent thoughts (other than their own) can open the doors of perception (though not in the way Aldous Huxley recommended), inculcate critical thinking and make masses immune to propaganda and empty rhetoric. In short, dictators and bigots, being the insecure nutcases they are, fear literature will liberate people from the tyranny of politics, religion, fundamentalism or whatever –ism they plan to deploy to subjugate their subjects.

But, calling the iconic Faiz poem anti-Hindu, as IIT-Kanpur has in a fit of mental squalor, only to back down later, is a new low, even by the standards of book-burning cabals.

Faiz: The poet of the East

Three great Urdu poets were born on the Indian soil before the Partition—Mirza Ghalib, Muhammad Iqbal and Faiz Ahmed Faiz. The three of them could easily be called the Milton, Yeats and Wordsworth of Urdu poetry.

But, there is a fundamental difference between their poetry. Ghalib, struggled with debt, vices, alcoholism, personal tragedies and lack of recognition all his life. So, he wrote mainly about his own travails and troubles, and the will to survive the challenges he faced. Although he chronicled the events that unfolded in 1857, Ghalib never dabbled in anti-establishment writing. He, instead, was not averse to writing qaseedas in praise of the British in the hope of securing a pension.

Iqbal started out as a secular, progressive poet, penning, among others, the famous ‘Saare Jahan Se Achcha’ before he succumbed to the lure of politics and the idea of a country based on religion. During this phase, he wrote extensively on the Ummah, its plight and even wrote a litany of complaint against God (Shikwa). Yet, most of his poetry retained its revolutionary zeal, the appetite for exhorting humanity to strive for greatness.

Also read | Never underestimate power of Faiz’s poetry, says daughter Saleema

Faiz was a communist, a romantic, and a progressive writer who stayed away from theology. He was more a Lenin-ist than an Islamist, dabbling in free thought, romanticism and academia. His father, Sultan Mohammad Khan, was a poor shepherd boy, who taught himself Persian, English and Urdu. In later life, he became a minister in the Afghan kingdom of Kabul. Faiz had an eclectic childhood because of his father, who, instead of sending him to an Islamic seminary, as was the fashion then, asked Faiz to study in a Scottish mission school.

In 1935, Faiz took up a job in Amritsar and became part of a literary circuit that changed his life completely. Some of his friends in Amritsar wrote stirring literature that was banned by the British, an experience that was to inspire Faiz later. While in Amritsar, he became part of the progressive writers association, whose members included some of the best names of the generation—Sahir Ludhianvi, Ismat Chugtai, Krishen Chander, Upindranath Ashk, Sibte Hassan and many others.

After the Partition, which he described in poignant words, Faiz stayed in Pakistan, where he was arrested by the Liaqat Ali Khan government on charges—denied by him–of participating in a conspiracy to overthrow the government. (Readers might be interested in knowing that the leader of this planned coup was Major General Akbar Khan, the man who led the tribal invasion of Kashmir in October 1947 under the pseudonym Brigadier Tariq). After his initial incarceration, Faiz remained in and out both of jail, and Pakistan. All his life, he was seen with suspicion by the Pakistani establishment.

The “anti-Hindu” poem

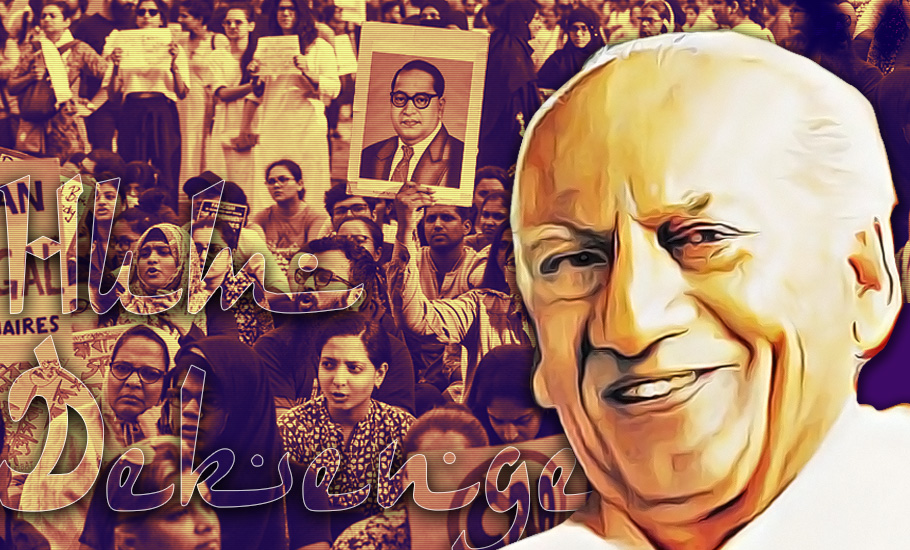

Faiz wrote his most iconic poem Hum Dekhenge to criticise Pakistani dictator General Zia and remind him of the will of the public and his own mortality. Some of its lines were so sharp that General Zia banned his poetry and its rendition. This ban was defied most famously by Iqbal Bano at a performance that has passed into folklore as a clarion call for resistance.

Defying General Zia’s ban on Indian attire and Faiz, Bano, an Indian who married a Pakistani in 1952, appeared on a stage in Lahore wearing a black saree. To the rapturous applause of the audience, amidst non-stop sloganeering and cheers, she sang Hum Dekhenge in her trademark voice that reached a crescendo with every verse, acting as a cue for louder slogans and theka of the tabla.

If you happen to listen to the recording that was smuggled out of Pakistan, the applause that erupts as she sings ‘Sab taj uchchale jayenge, sab takht giraye jayenge (all crowns will be tossed, all thrones will be upturned)’ will give you goosebumps— provided you are not a bigot or buy the “anti-Hindu” argument.

In an ode to the collective heritage of the sub-continent—Faiz is as much Indian as he was Pakistani—Hum Dekhenge has become the anthem of people protesting the new citizenship law passed by the Narendra Modi government. In tandem with Rahat Indori’s famous assertion, Kisi ke baap ka Hindustan thodi hai, it has become the background score of the protests.

Controversy erupted over the poem when some students protested its recital on the IIT-Kanpur campus, calling it “anti-Hindu.” In response, the administration announced a panel to look into the “anti-Hinduness” of the poem, a decision it later revoked.

So, what’s “anti-Hindu” about Hum Dekhenge? Well, if the rightwing can call the Taj Mahal anti-Hindu, this isn’t much by their bigoted standards. But, what is more surprising is that such ignorance, bigotry and intellectual poverty pervades a premier institution like the IIT. Next, they might call Othello and Hamlet Christian and seek a ban on Saare Jahan Se Achcha, because it was written by Iqbal.

Perhaps their bigoted brains have been tickled by two lines in the poem. Faiz wrote, ‘Bas naam rahega Allah ka’ (only the name of Allah will survive). Here, Faiz uses Allah as the Supreme Being who is witnessing everything. In this context, the critics need to be reminded what Sahir Ludhianvi wrote: Allah tero naam, Ishwar tero naam (both Allah and Ishwar are the same).

In another line, Faiz wrote: Uthega ‘Anal Haq’ ka naara (people will proclaim ‘I am the truth’). Those calling it anti-Hindu would bury their head in shame if they knew its history and philosophical similarities with the Hindu literature. ‘Anal Haq (I am truth)’ was first proclaimed by a 9th century Sufi mystic Mansur al-Hallaj. Finding his assertion anti-Islamic (which it wasn’t), the then Abbasid Caliph ordered the Sufi scholar’s execution on the banks of the Tigris. Many Indian scholars argue that ‘Anal Haq’ is similar to the Sanskrit aphorism ‘Ahm Brahmasmi’. Calling an idea rooted in Hindu philosophy as “anti-Hindu” is just laughable.

The hallmark of great revolutionary poetry is that its appeal transcends all divides, it scares tyrants of all ages, religions and geographies. It shames bigots of all faiths. Hum Dekhenge passes this test with flying colours. It terrified the Pakistani dictator then, it scares his ideological followers in India now. It was called anti-Islamic then, it is being labelled anti-Hindu now.

General Zia would be smiling, if he still had the ability to do so. And therein lies a lesson for all fascists and bigots.

In Hum Dekhenge, Faiz had warned that lightening would fall on tyrants and dictators (aur ahle-hakam ke sir upar bijli kad-kad kadkegi). A few years later, the subject of his wrath, General Zia-ul-Haq, died when a plane carrying him exploded mid-air over Bahawalpur. Such was the impact that only the General’s dentures were found, immortalising the place where they fell forever as Jabra (dentures) Chowk (square).

If only he had the luxury of a jaw and grave, General Zia would be smiling over the madness over Hum Dekhenge in the neighbourhood.