- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

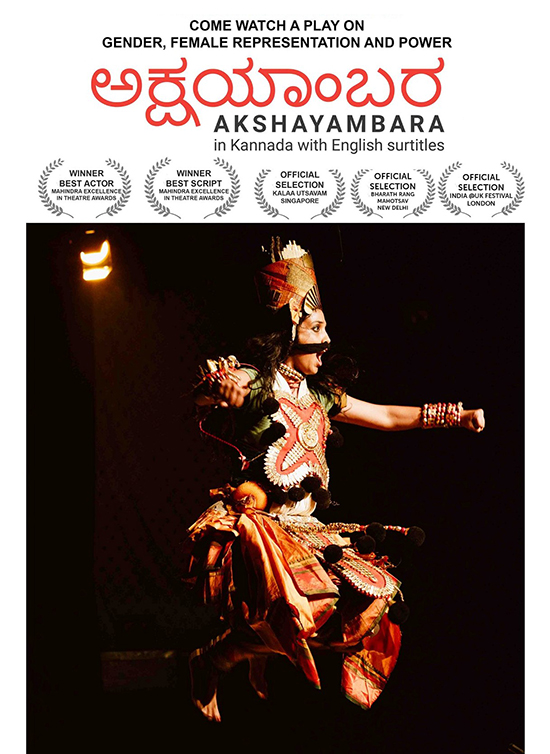

How Yakshagana art is keeping with the times, even in a Covid-19 world

In Akshayambara, an experimental Kannada play, the director uses contemporary theatre art and Yakshagana, the traditional multi-dimensional folk art of Karnataka, to weave in a story of gender role reversal. For long, men have played women characters in movies and plays. But how would people take it if a woman played the role of a man? Akshayambara revolves around this central question...

In Akshayambara, an experimental Kannada play, the director uses contemporary theatre art and Yakshagana, the traditional multi-dimensional folk art of Karnataka, to weave in a story of gender role reversal.

For long, men have played women characters in movies and plays. But how would people take it if a woman played the role of a man? Akshayambara revolves around this central question and operates between the binaries of a man and woman.

While the director Sharanya Ramprakash plays the epic character Dushasana (Kaurava king) and Prasad Cherkady, 32, a theatre and film personality in Karnataka, dons the role of Draupadi.

Throughout, the show travels between the stage and the green room, and explores the opposing realities.

From tradition to modernity, urban and rural, masculinity and feminism, and more. The play won two awards—for the ‘best original script’ and ‘best actor’ (male) at the Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards in 2016 and received accolades for its progressive thought-provoking concept.

Ever since, it’s widely played across theatres in India, the UK, and Singapore.

The play takes Yakshagana, a male-dominated art that existed for over 800 years, and questions the conventional wisdom narrated through the epic tales. The folk art is a mix of dance, music (though percussion instruments), drama and costume and make it’s a strong medium of communication with a high-pitched voice of the narrators and stage performers.

Traditionally, the themes in Yakshagana were based on folklore, mythologies like Ramayana and Mahabarata and moved as a temple art for generations. But over the years, it’s changing and artists are adapting to modern themes and interests.

Cherkady, 32, a theatre and film personality who’s been practicing Yakshagana since the age of seven, takes us through the changing tales of Yakshagana and how the artform is taking new turns with Covid-19 forcing people dependent on it to look for alternative arrangements with theatres being shut for long (now reopened across cities).

Evolving with progressive themes

“When I read historical books, I see varied responses to the changes and evolution in the art. Some went with the flow, some artists expressed anxiousness and some resorted to blaming the new concepts for deviating from traditions,” Cherkady says.

With Akshayambara, he says it was a role he always wanted to play and challenge the popular concept. The play gave him that platform and allowed him to ask uncomfortable questions with gender reversal by meddling with the tradition where the actors fight, understand each other and also find a common ground to settle. “Every time we have new adaptations, we should welcome it,” he adds.

The artform explored topics beyond Indian mythologies and broke the religious barricades with plays on Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, on preachings of Basavanna and Akkamahadevi among others. Later, novelists like BV Karanth and Shivaram Karanth even adapted Macbeth and other works of William Shakespeare.

“A play titled ‘Papanna Vijaya Gunasundari’ is based on Shakespeare’s King Lear. It was adapted five decades ago. It’s Indianised so much that we feel it’s ours,” he says. Adaptations have been happening for long and experimental theatre existed even before.

Considering that coastal Karnataka, where Yakshagana flourished, has a strong presence of the Bharatiya Janata Party, some artists even dabbled with political themes. One such play was titled Narendra Vijaya that deals with the life and exploits of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. And in recent months, certain troops also performed Yakshagana with Corona awareness as the theme.

Transition to online

With Covid-19 making theatres go online, the artform also attracted new audiences across the globe and evoked the interest of Yakshagana enthusiasts.

Prof Mahabala Hegde of Yakshagana Academy in Bengaluru says close to 3,000 Yakshagana artists and nearly 10,000 support artists are dependent on this profession.

“With online, we are able to attract the new audience and reach worldwide. But it cannot be a platform for all. Only some famous ones are able to attract clicks,” he says.

Hegde says some even tried to do shows in the English language with limited success. It’s difficult to match the beat and maintain the same tone while doing in a different language,” he adds.

In the urban centres, shows catered to the new audience with songs and drama in Kannada and the narration in English. Artists are looking at newer avenues to learn and showcase talent.

Ujire Askhok Bhat, another senior artist from coastal Karnataka, says, “People have given good encouragement to at least Thalamaddale, one of the forms of Yakshagana.”

But, he adds, as online viewers mostly watch it for free with live shows or YouTube videos, it’s not economically viable for the drama troupe. It only promotes the art.”

His group, Kuriya Vittal Shastri Yakshagana Prathistana, a Trust based in Ujire, Belthangady taluk, experimented with a week-long programme with one character playing multiple roles so that the audience can get to experience the variations an actor can produce.

Not just shows, even Yakshagana teaching went online. Cherkady, who’s been teaching the art for 12 years, took to the online mode and has been regularly conducting classes every weekend since May last year.

“Although I used to teach online on ad-hoc basis, it became organised after the lockdown because we were compelled to do it. For some, it was a question of survival,” he says.

“We had artists and Yakshagana enthusiasts from remote places and from abroad joining us to learn new ways. In the Initial days, 60-70 students came to learn,” Cherkady says. His team conducts three months courses and he says one can learn the basics of Yakshagana in nine months.

“Going online taught us to be more organised as we had to record videos in advance, have more supportive material to suit the syllabus and good gadgets to present,” he adds.

What (teaching Yakshagana) started as a means to earn his pocket money during college days has become his profession today.

Cherkady, who’s also into acting in movies, shuffles between the two platforms. His enthusiasm for Yakshagana started young as he got exposed to the art as a kid in Coastal Karnataka. He says his grandfather used to listen to ‘Akashvani’ (radio) and make him dance to Yakshagana songs.

Unlike in Kerala or Odisha where Kathakali and Odissi are used in movies widely, Yakshagana did not find the same place in Kannada films. Also, like the Mysore-based art form Veera gathe or Kamsale, Yakshagana did not feature much in Kannada movies. Cherkady is now trying to bridge that gap. He’s now all set to incorporate Yakshagana in at least four upcoming movies.

Ujire Bhat, however, says Yakshagana is restricted to four of the 30 districts in Karnataka—Dakshina Kannada, Udupi, Uttara Kannada, and Shivamogga (Malnad region).

But Academy director (Mahavala Hegde) disagrees, saying it’s not restricted to coastal Karnataka as other forms like Moodalapaya and Ghattadakore are popular in 14 southern districts around Kolar, Chikkaballapur and Tumakuru region.

The fact that the Academy was set up in Bengaluru was to encourage the art state-wide and respect all forms. Instead of setting it up in coastal Karnataka — which has a rich culture of Yakshagana — having the academy in Bengaluru helped garner political support for the art, he adds.

“From the administration point of view, Bengaluru helps us lobby for funds to promote the art. The academy has close to 1,500 registered members with 10 years of experience who were all provided with Rs 2,000 as financial aid to cope with the Covid crisis during the lockdown period.”

But Bhat begs to differ. “It (Yakshagana) is not widely known beyond four districts. So our voices are not being heard and our concerns don’t become a political issue,” Bhat says.

The government, he adds, needs to allocate more funds and organise more shows to promote the art and support the artists. “It should also be taught in schools and colleges so that the art is popularised.”