- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

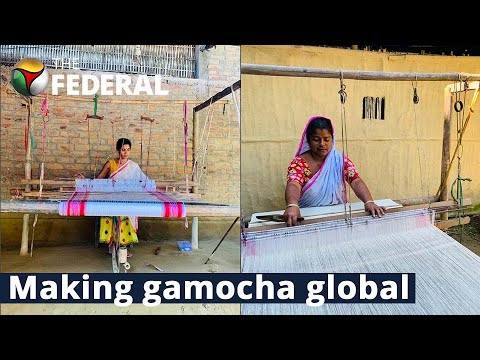

How wrapping in the traditional art of gamocha-making is infusing life in an Assam village

Phulmoni Das was at her wit’s end living in a picturesque, but off the map village called Sagolikota under Lahowal development block. With an especially-abled husband, she didn’t know how to send her three daughters to school. To meet the daily expenses of running a household, Phulmoni worked at the tea garden in Assam’s Dibrugarh district, where work remained inconsistent and...

Phulmoni Das was at her wit’s end living in a picturesque, but off the map village called Sagolikota under Lahowal development block. With an especially-abled husband, she didn’t know how to send her three daughters to school. To meet the daily expenses of running a household, Phulmoni worked at the tea garden in Assam’s Dibrugarh district, where work remained inconsistent and wages low.

Though Sagolikota has seen some development in the form of pucca houses, a patchy network of roads and water connectivity, with no real livelihood opportunities, the plight of Phulmoni’s family is a shared one. Women of the village work at tea gardens and the men work as farm labourers. Only a few own land. Both men and women are forced to venture out of the village to find work.

None thought there was any other way to live and meet expenses until Sewa, a Dibrugarh-based NGO, came to the village with an order to make 500 traditional hand-woven gamochas, also known as gamusa. The village wasn’t unfamiliar with gamocha-making. No village in Assam is. But to the surprise of the villagers of Sagolikota, the order had come neither from Assam, nor any other part of India. Instead it came from the UK and the US.

To ready the order in time, Sewa delegated the work to 30-odd women of Sagolikota.

Phulmoni was among the 30 picked up for the job. The women get Rs 5,000 per month for the work. As part of their work arrangement with Sewa, the women will get the same amount to make gamochas from October to April which is when the demand for gamochas peaks due the festive season. They will also get Rs 2,000 to Rs 2,500 every month during the lean business phase from May to September.

“We never thought that our handmade gamochas will one day be able to go beyond the state, or the country,” says an elated Phulmoni.

People of Assamese origin settled in the US and the UK have ordered the gamochas to gift them to their near and dear ones during festivals and weddings. Phulmoni, Snehalata, Bhadrawati, Madhumita and Nirmali are among the women who have already prepared 400 of the gamochas that were ordered and are working hard to complete the rest of the order by this month-end.

“Sewa has informed us that we will earn more money now. I could not pursue studies because of various financial and social constraints, but now I think I will be able to educate my daughters,” Phulmoni said with tears welling up in her eyes.

Bhadrawati, whose husband is a daily wage earner, said that the development will infuse a lot of confidence in the women. “This is a more dignified work and we are putting in more hard work because this work makes us happy. Everyone is happy,” she said.

Gamocha-making as an art is common to villages in Assam and Sewa had been working with women of Sagolikota earlier too but those were domestic orders that came with little money as the traditional art of gamocha making took a hit in recent years in the face of competition from power-loom gamochas taking over the market.

“We provided the women of Sagolikota knowledge in the traditional art. They have been making gamochas on and off when they find work in power-looms but our foreign clients want gamochas made in traditional form,” said Jyoti Bhagat, programme coordinator at Sewa.

Threat to the traditional art

The Assamese traditional scarf, or gamocha, which in many ways is the most easily recognisable markers of Assamese identity, received the Geographical Indication (GI) tag from the Geographical Indications (GI) Registry in December 2022, becoming the 10th product from Assam to get the tag.

While it is unclear when actually gamochas seamlessly became a part of Assamese daily life, there are records dating back to the 14th century mentioning its usage by the Ahom kings who ruled Assam for 600 years. Gamocha is so neatly wrapped around Assamese culture that it is gifted to elders as an expression of respect, affection for the young, and love between men and women. It also enjoys a sacred significance and so is used on the Thapona (altar). Known as God’s cloth, gamocha is richly decorated with designs.

According to the Handloom census of 2009-2010, second only to agriculture, Assam’s handloom sector provides livelihood to more than 25 lakh weavers. Handloom weaving has a significant presence in the socio-economic life of Assam since ages. The loom is a ubiquitous possession in almost every household. The tradition of weaving is passed on from one generation to another, allusions to which are available in Assamese scriptures and literature.

But with imported Chinese items dominating the markets, traditional weavers have been increasingly facing hardships over the years.

The word gamusa is derived from two Assamese words — ga, which means body and musa, which means wipe. Put together, gamusa quite literally means a towel. The standard size of a handloom-woven phulam (floral print) gamusa is 150 cm in length and 70 cm in width so that when draped around the neck its ends fall a few inches below the navel.

While the cotton textile was traditionally hand-woven in white with red borders, over the years the traditional art suffered a setback with Indian markets getting flooded with Chinese gamochas. While the average price of a hand-woven gamocha is between Rs 100 to Rs 150, where the weaver earns Rs 75 to Rs 80, the cost of a traditional designer gamocha can also climb from Rs 300 to Rs 1,500. Chinese manufacture it on a power-loom selling it in acrylic and polyester, which are unable to soak water, for Rs 50 to Rs 60.

In the traditional way of warping, it takes a long time for artisans to warp the yarn. And so when it comes to mass production, traditional methods lag because the process is time consuming, requires more space, and more manpower. Put together these factors make traditional gamochas costlier.

Making a traditional gamocha takes about 1.5 days of 5-inch design as the motif designs are handmade. In comparison, 2-3 gamochas of 5-inch design can be made using power-looms, which uses a jacquard machine for designs.

Given that it is not easy to differentiate between the two, consumers opt for the cheaper gamochas. Even the Regional Office of Textiles in Kolkata, a recognised laboratory for testing samples of clothes, failed to make the distinction. This prompted the Directorate of Handloom and Textiles to seek a GI tagging for the product.

Interestingly, according to the Handloom Reservation Act of 2010, the Assamese gamochas are reserved items in the handloom sector, which means manufacturing them on power-loom is a violation of the Handloom Reservation Act.

In the January-March quarter of 2017, the Union Commerce Ministry reported a trade deficit of $51 billion with China. In March 2018, the district level enforcement squad of Darrang district in Assam conducted a drive in Mangaldai and Kharupetia markets as part of an effort to assess the impact of Chinese imports on India’s domestic production. The raids that reportedly covered seven textile commercial establishments led to seizures of a nearly 3,535 power-loom gamochas estimated to be worth Rs 4,92,300.

Cultural alteration

The power-loom production hasn’t just hit domestic production but also altered the cultural meaning of the floral motifs that are weaved on the borders of gamochas.

The power-loom gamochas place two-sided flowers on every variety. Traditionally, however, only gamochas given during wedding ceremonies, called dora boron gamusa, carry two-sided flower motifs.

“This is because it is believed that the body of lord Bhisnu had both the characteristics of a man and a woman. The right side is for a man and the left for a woman. Floral designs with borders mean the lives of a boy and a girl merging together,” Deepak Boarah, a researcher explained.

The size of a dora boron gamusa is 175 cm× 70 cm. The clothes sent by a bride’s family to the groom’s house must include dora boron or jor gamusa.

There are similar specifications and customs attached with various types of gamusas made for specific occasions. For instance, the aanakata gamusa is woven for special rituals such as weddings. Only a single piece is weaved at one time and is separated from the loom without cutting the warp yarns. Again, Bihuwan gamusa is used during Bihu and gifted as a token of respect. Its size should ideally be 150cm× 70cm. The tioni gamusa is worn as a wraparound or lungi by males. The size of this plain weave is 200cm×100 cm.

Ray of hope

With the Assamese gamocha winning a GI tag, which acknowledges that the gamocha has a specific geographical origin in Assam and possess qualities that are due to its origin in the state, the handloom weavers may find a fresh lease of life.

Overseas orders are may also act as a catalyst to boost the demand for traditional gamochas which can, in turn, give a fresh impetus to those engaged like Phulmoni, in the work since generations, forced to look for work in tea gardens and farms to eke a living.

“The response from our overseas clients has been very encouraging and many have expressed a desire to place bigger orders and also let others know about the availability of authentic Assamese gamochas in faraway countries to help boost business. We are working on capitalising on this so that we are able to help more women and their families like we did in Sagolikota,” said Jyoti Bhagat.