- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How women mountaineers rose to the top

On March 16, Piyali Basak, a 32-year-old mountaineer based in Chandannagar, West Bengal, set out to conquer two peaks higher than 8,000 metres in the Himalayas. The first peak, Mt Annapurna (8,091m), the world’s 10th highest peak in north-central Nepal, is considered among the toughest to climb. The second one, Mt Makalu (8,485m), on the Nepal-China border is notorious for its...

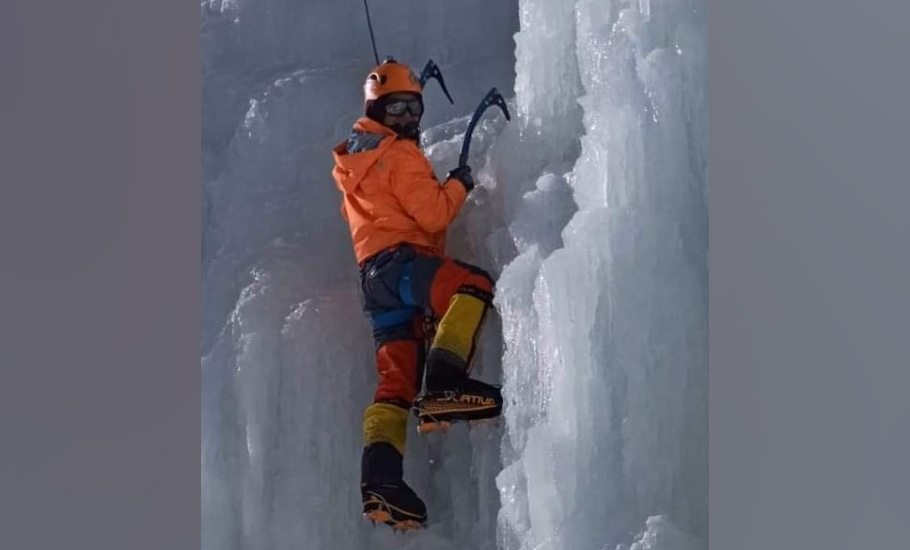

On March 16, Piyali Basak, a 32-year-old mountaineer based in Chandannagar, West Bengal, set out to conquer two peaks higher than 8,000 metres in the Himalayas.

The first peak, Mt Annapurna (8,091m), the world’s 10th highest peak in north-central Nepal, is considered among the toughest to climb. The second one, Mt Makalu (8,485m), on the Nepal-China border is notorious for its knife-edged ridges.

Notwithstanding the challenges of elements and the tough terrain, Piyali, following in the footsteps of her previous successful summits of Mt Everest (8,848 m; the highest), Mt Lhotse (8,516 m) and Mt Manaslu (8,163 m), is confident of conquering the two peaks. She won’t use supplemental oxygen that most mountaineers need in the thin air of the upper Himalayas. She once said, “I can survive fine without oxygen just like Sherpas who have grown up in the thin air environment.”

For the gutsy mountaineer the stiffest challenge, however, is an acute financial crunch. As a primary school teacher near her home, she earns just enough to feed her family, including an ailing father. Truly speaking, mountaineering is a sport beyond her means. Above all, she is a woman – a minority in the male-dominated adventure sport fraught with the risk of death and permanent disability.

Scaling high peaks in Nepal comes with hefty price tags. The Nepal government charges around $25,000 for an individual climber. In addition, the mountaineers must rent or buy expensive climbing equipment (such as ropes, tents and ice axes) and hire Sherpa guides.

Piyali, who has managed to raise just Rs 9 lakh out of the total Rs 31 lakh she is required to pay to the Kathmandu-based commercial adventure operator, expects to raise the remaining funds from various agencies, including sports clubs and philanthropists. Speaking to The Federal, she says, “I am sure people will extend their help as they have done during my previous trips.”

Scaling peaks costs women more.

Debasish Biswas, an accomplished mountaineer, who has scaled seven 8,000m-plus peaks in the Himalayas, explains, “The cost of climbing is higher for women because they are a minority.” Previously most women climbed in groups and they didn’t have to share tents with men.

“Nowadays, most women climbers go solo. For them, getting a female-only tent is difficult and expensive,” he points out. According to him, female climbers need privacy as they feel uncomfortable sharing a toilet with men or having to deal with issues like menstruation. “If a woman has periods along with an injury incurred during climbing it becomes extremely risky,” says Biswas.

Bachendri Pal, the first Indian woman to summit Mt Everest, says her journey to the top has not been an easy one for several other reasons, including gender discrimination.

Born in Nakuri, a small village in Uttarakhand, she had to fetch wood for cooking from the forest in her early days. In the interview Bachendri told this writer, “Then I’d walk five kms to reach school and also look after my younger siblings at home.”

Women’s education was a luxury in her village. She recalls, “The social perception in those days was that girls should get some amount of education, do a job if needed, preferably as a teacher, and then get married.”

Bachendri saw her elder brother working for the Border Security Force and got trained in mountaineering. She reminisces, “Although we lived in a hilly region, people didn’t get any formal training in mountaineering. When I saw my elder brother encouraging my younger brother to get this training I wondered why not I.”

Colonel Prem Chand, who had conquered Mt Kanchenjunga, India’s highest peak in 1977, used to visit the Nehru Institute of Mountaineering (NIM) near Bachendri’s home. “Once when he came to visit our village he motivated me to take a course in mountaineering.”

By then, she had completed MA and BEd and her family wanted her to get a “cushy teacher’s job”. But after she completed the basic mountaineering course at NIM, she was selected for pre-Everest expeditions. “I used to go to the jungles, carry weights, bring wood, grass and heavy loads during practice sessions despite resistance from my family and neighbours,” she says. Despite the lack of social support, she decided to carry on her training and practice.

In 1983, when she got a job offer from TATA Steel, it dawned on people that this is also a career that can bring you a job. A year later, the Indian Mountaineering Foundation sponsored and organised a Mt Everest expedition, inspired by the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. The team comprised 20 climbers including six women like her.

“During the expedition it was necessary to prove my climbing prowess as male members discriminated against us. Although, they did not let us carry our goods or do much work during the expedition, they later accused us of being inactive. ‘They carry cosmetic boxes and are incapable of hard work’, they ‘d say,” she reminisces.

After her Mt Everest summit, Bachendri got many job offers from several companies, but did not leave TATA Steel, which created an Adventure Foundation (TSAF) under her leadership to train mountaineers. “Using the TSAF platform, I started work on women empowerment and continued it till my retirement two years ago,” says Pal, who is still connected to this foundation.

Deepali Sinha, is a pioneer woman mountaineer in India now living in Calcutta. She was among the eight members of a team of women mountaineers from West Bengal who conquered Mt Ronti (6,029 m) in the Garhwal Himalayas in 1967.

She said, “In those days, women had a tough time in society. Girls or women were not even supposed to be seen on the terrace or balcony of the house after sundown.” However, her father, a doctor, always encouraged her to take up sports.

Deepali used to be a Girl Guide — originally designed in the early 20th century to encourage women to go camping and hiking in groups — in her school in south Calcutta. She had heard about the Mt Everest conquest of Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary but she had never seen a mountain. She was studying for a BA in English at Shri Shikshayatan College in Calcutta.

She reminisces, “One day during the National Cadets Corps (NCC) parade in our college campus, a subedar showed us a circular that NCC will provide scholarship for mountaineering training at the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute in Darjeeling.”

Women from all provinces were supposed to be selected for the training. “Three of us were initially selected, but I was rejected at the medical test because I was underweight (80 pounds, or 36 kgs). They said my light frame will blow me away during a strong blizzard,” she recalls. “I was terribly upset, but our NCC lady officer Anjali Sarkar took me to Darjeeling despite me being rejected,” she recounts.

In HMI, she had to prove her worth by passing all the fitness and endurance tests required for the mountaineering course to qualify for training under legendary mountaineer Tenzing Norgay. “He was my teacher, friend and neighbour,” she says, showing an album of pictures in her drawing room covered with various certificates, medals and framed pictures of world’s best known mountaineers. She completed her basic and advanced training by 1967.

Unlike Bachendri, Deepali did not face any family hurdles during training or expeditions. “My father was so progressive that he predicted women would soon rule the society. A few years later, Indira Gandhi became our Prime Minister,” she says. He convinced all her relatives, neighbours and parents of teammates for her first expedition.

Meanwhile, a group of male mountaineers from Calcutta scaled Nanda Ghunti, a 6,309 m peak in Garhwal, in 1960. The news got wide press coverage and created a frenzy among youngsters in Bengal.

“Inspired by their feat we – a group of women mountaineers – decided to launch a similar expedition,” Deepali recalls. They announced their intention in a press conference and collected funds for the trip. But just 10 days before the expedition, a letter arrived from Indian Mountaineering Foundation (IMF), the apex body based in Delhi that in any expedition above 20,000 feet height, at least 40 per cent of team members should have an advance training in mountaineering. “I was the only one in the team with such training,” she says. So, the all-women’s-team’s application for the expedition was rejected.

This irked Gandhian leader Prafulla Chandra Sen, the former chief minister of West Bengal. He immediately took up their cause saying this was “gender discrimination” and wrote a strong letter to Indira Gandhi.

Deepali says, “I, along with a teammate went to Delhi to deliver the letter in person to Mrs Gandhi. Sen suggested should Mrs Gandhi fail to organise the permission for the expedition, we sit for a dharna and fast – a Gandhian method of peaceful protest – and threaten to bring more people from Calcutta.”

“However, we didn’t have to resort to such protests,” she adds. “On the contrary, Mrs Gandhi welcomed us in a special visitor’s room.” Sen’s letter was so impactful that Mrs Gandhi immediately instructed the president of the IMF, who was also a defence secretary, to take necessary steps to enable our climbing. He relented and allowed us to scale Mt Ronti.

“The publicity helped us gather requisite funds and get equipment,” says Deepali. The press coverage also helped remove all social and family obstructions that some teammates faced. She says, “But there were other stumbling blocks. The transport infrastructure was not good and we had a hard time gathering climbing equipment and other essentials required for the expedition. By the time we reached the base camp we were quite exhausted,” she says.

Deepali participated in 12 expeditions ever since she conquered Mt Ronti leading various groups of women mountaineers. Many more young mountaineers followed in her footsteps to organise and lead teams of women mountaineers.

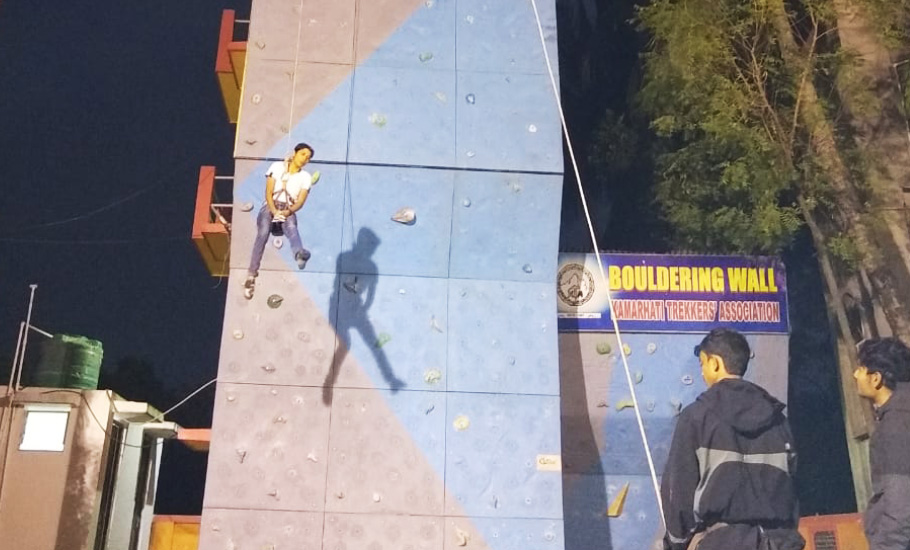

Mahua Biswas, a 35-year-old mountaineer, has been participating and leading various teams of women mountaineers for more than a decade. One of the teams, comprising nine other women climbers, conquered Mt Tenchenkhang (6,010 m) in the Sikkim Himalayas in 2015. She participated in 10 other expeditions, including conquering Mt Manirang, Mt Nanda Ghunt etc.

Mahua also has been facing quite a lot of social challenges in her way. After she lost her father in a fatal road accident when she was just three, she and her mother had to take refuge at her maternal grandmother’s home in Bangaon, a small town 80 kms north of Calcutta. Five years after her father’s death her mother, a former state-level athlete, kabaddi and kho kho player, got a job in a government bank through sports quota.

Later, they moved to Habra when she got admitted to Banipur Women’s College. A physical education teacher advised her to join a rock climbing course in the hills of western West Bengal in Purulia and Bankura. She followed this up with a basic course in HMI, Darjeeling, and an advanced course at NIM, Uttarkashi in 2011.

Her mountaineering skills helped her crack a job in the Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs, Calcutta, just after she graduated. She could have easily attempted to summit Mt Everest but did not want to leave her ailing mother alone at home in a suburb of Calcutta.

“What will happen to my mother if I lose my life in an avalanche? Who will take care of her?” she said. So, now she goes for shorter expeditions that are less expensive or sponsored by the state government.

Since longer expeditions are no longer feasible for Mahua, she’s shifted back to sport climbing – in which athletes climb through artificial walls embedded with anchors.

Inclusion of sport climbing in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics has turned it into a coveted sport. Mahua’s superior skills helped her win several gold medals at the state and national level sports climbing championships.

Despite many challenges, these women mountaineers carry on because of their passion for mountaineering, their love for the Himalayas and for the accolades that come their way. Also, many young women look up to them and consider them as their icons.