- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How this Tamil Nadu village became a refuge for intercaste couples

In their 60s, P Dhanabagyam and Shanmugam look far from the besotted couple which once bravely fought caste barriers and parents’ anger to make a home together. But their love is every bit young even after more than 40 years of marriage. In the late 1970s, Dhanabagyam committed the “mistake” of falling in love with a Dalit boy. Her Vanniyar family (an influential intermediate caste)...

In their 60s, P Dhanabagyam and Shanmugam look far from the besotted couple which once bravely fought caste barriers and parents’ anger to make a home together. But their love is every bit young even after more than 40 years of marriage.

In the late 1970s, Dhanabagyam committed the “mistake” of falling in love with a Dalit boy. Her Vanniyar family (an influential intermediate caste) was vehemently against the union. With no other solution in sight, Dhanabagyam eloped with Shanmugam and came his village — S Patti — in Tamil Nadu’s Dharampuri district. Back in her village in neighbouring Veppampatti, her parents were baying for the couple’s blood. “They wanted me dead, mostly because of the humiliation they had to face from village elders since their daughter ran away with a Dalit boy. My parents were ostracised and even barred from drawing water from the village well,” she recalls the ugly aftermath.

Today, Dhanabagyam has no regrets about her decision and happily stands by other such intercaste couples taking refuge in S Patti, which by now has made a name for itself for coming to the rescue of such distressed couples. “I can’t forget how the villagers helped me cope with the situation when I was expecting our first child. Even though I was an outsider who was not just new to the village, but also belonged to a different caste, this became my home and the villagers my family,” she says.

Dhanabagyam and Shanmugam see their own reflection in young Vasuki and Gopal (names changed). Interestingly, both Vasuki and Gopal don’t belong to S Pattii village. “But fate brought us here,” says Gopal. The couple has been blessed with a baby boy six months ago.

Gopal and Vasuki landed in the village after a tumultuous journey and a failed attempt to run away to Mumbai.

Love bloomed between the young couple from two different villages in Kallakurichi district seven years back as their paths crossed at the common bus stop at Kallakurichi town every day on their way to their respective colleges. Gopal’s father, a clerk in the office of the Village Administrative Officer (VAO), and Vasuki’s father, a local AIADMK functionary, were old friends. The families knew each other for years, but both Vasuki and Gopal were not aware of the fact that they belong to different castes.

“Almost two years into the relationship, one day Vasuki asked me about my caste. It was only then I came to know that she was a Vanniyar. And I belonged to the Adi Dravidar community [Scheduled Caste]. Fearing that her family would never accept our relationship, she stopped speaking with me almost immediately. But that didn’t continue for long and we were back together within a few months,” Gopal says.

In November 2020, Vasuki informed Gopal that her family was looking for a groom for her. Notwithstanding the friendship between the fathers, Vasuki and Gopal both knew her family would never agree to their marriage. The couple soon decided to elope as one of Gopal’s relatives in Mumbai extended support.

On December 1, 2020, they decided to take a car to Bengaluru airport and board a flight from there to Mumbai. “On the night of December 1, I picked her up from her house without anyone noticing us. When we thought that everything was going as per plan, we were stopped by the police at the Hanumantheertham checkpost in Dharmapuri district on our way to the Bengaluru airport. On enquiring, the police found out that we were planning to get married without our parents’ consent and immediately rang them up. We were then taken to the nearby police station,” he narrates.

“We were scared of what awaited us when a few villagers from S Patti landed at the police station and reasoned with the police that we should be let off. We only learnt later that while the police stopped us at the checkpost, a resident of S Patti was passing by [Hanumantheertham checkpost is barely 1 km away from S Patti village]. He immediately reached his village and informed others who rushed to our rescue.”

The S Patti villagers asked the police officers why the couple was being held against the law. “The villagers argued that it was our right to marry the person of our choice with or without parents’ consent once we are of marriageable age. The officials then asked Vasuki whether she was doing all this of her own volition. Once she expressed her desire to be with me, they let us go,” Gopal recalls.

But before the two could leave, Vasuki’s parents reached the police station. The male members of the family asked her to return with them but when she refused, they threatened to kill them. Back in the village, Gopal’s family had to flee their house after a few members of the Vanniyar community, along with Vasuki’s family, reached Gopal’s house and threatened to kill them.

“Sensing the seriousness of the situation, the villagers from S Patti suggested that we stay with them in their village, promising to do everything in their capacity to support us. With no other option, we agreed to move here,” Gopal says.

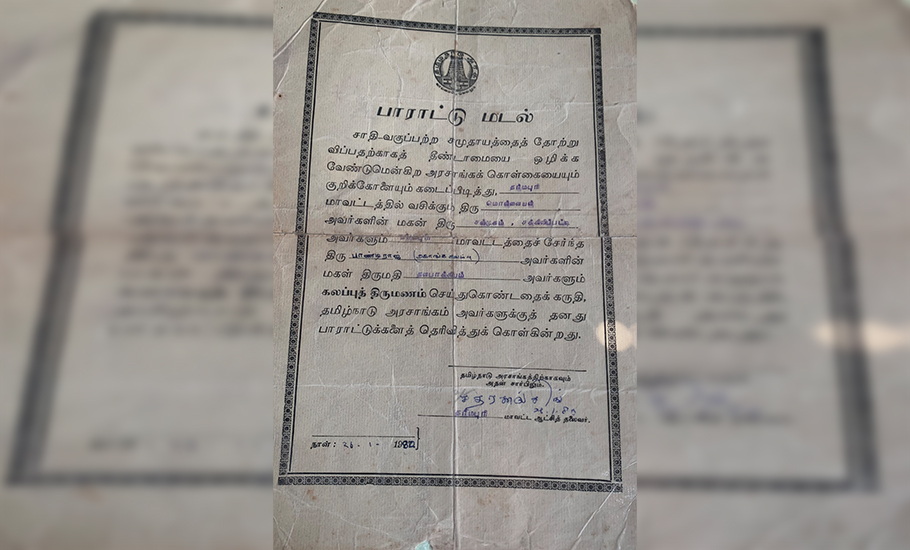

On December 2, the villagers organised a wedding for the couple at a nearby temple and almost everyone from the village participated in the ceremony. The marriage was registered immediately. The couple began to stay in the house of K Sakthivel, a villager who also married outside his caste.

“Even though it was just a single-bedroom house, they accommodated us and took care of all our expenses. After two months, as we did not want to bother them any longer, we expressed our desire to move out. The villagers then accommodated us in one of the vacant houses in S Patti. We thought they were renting out the house. But till date they have not accepted any rent money, not even electricity bill,” Gopal says.

Around six months after the wedding, Gopal adds, Vasuki’s family again forced her to return home and marry a person from their caste. “Her father tried to emotionally blackmail her saying he had lost respect in his community because she married a person from the Scheduled Caste. When she refused, they told us we can never enter our villages ever again as they would kill us if we were seen around.”

Whenever Gopal and Vasuki see other intercaste couples reuniting with their parents, it breaks their hearts. “It’s sad, why did that never happen to us?” Gopal wonders. But the love showered by the villagers of S Patti fills the void. “They keep us motivated and make us feel like a family. This village is our home now,” he adds.

The feeling is shared by most intercaste couples living in the village. “Marrying Parameshwari is one of the best decisions I made in life. Even though her family opposed it, my family and the villagers supported us,” says K Thiruvenkatam, 36, a Dalit villager from S Patti.

Parameshwari, originally from a nearby village in Kanchipuram district, goes on to explain how her father, who used to treat Thiruvenkatam like a son, stopped talking to both of them after knowing that the two were in love.

“It has been 10 years since we married and have two children,” she says. Her father is still angry with her for marrying a Dalit boy. “Unlike the S Patti villagers who invite us to all events, we are never invited by her family for any of the functions, including her sister’s wedding. We expect nothing but their love,” Thiruvenkatam adds.

The year that changed the village

Like most villages in Dharmapuri district, which is infamous for being highly polarised on caste lines, S Patti is dotted with symbols and flags attesting to its socio-political credentials. A plaque with the images of BR Ambedkar, Periyar (EV Ramasamy) and Thol Thirumavalavan (Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi, also famous as VCK, leader) guards the village entrance. Atop it flutters a VCK flag high in air, almost touching the electric wires. The lane leading to the village takes one to a statue of Ambedkar, coloured in a golden hue, within a wire mesh enclosure.

The village, which accepts and embraces those shunned by their own families, has about 3,500 voters with most hailing from Scheduled Castes, especially the Adi Dravidar community. S Patti now has over 100 intercaste couples, and in most cases, at least one of them belongs to an SC community while the other belongs to ‘upper’ or ‘intermediate’ castes such as Vanniyar, Chettiar or Viswakarma.

The economic conditions of Vaniyars are almost the same as the Dalits as about 230 people in the village are in government jobs, while more than 1,000 people are in private jobs, which mostly involve teaching. The rest either work as farm labourers in neighbouring villages, or travel to Coimbatore and Tirupur to work at construction sites.

While the village never was averse to intercaste alliances, it was in 1982 that S Patti first made headlines.

“There was an incident in 1982 when a villager, Parithiammal, married Vijaya from the 24 Manai Chettiar caste. Shortly after the wedding, the woman’s family, along with their supporters, entered the village and attempted to attack us. That was when the S Patti villagers came together and chased them away,” says A Vasu, 54, one of the villagers.

Shortly after the incident, the then district collector V Manivannan, along with social activist Sadayappan, conducted an awareness programme to eradicate caste discrimination across the district. As a part of the efforts, several cultural programmes and dramas were staged in villages to spread the message.

“But the political awakening dates back to the pre-independence period of 1940s when Appadurai (a school teacher), Deivam (a doctor) and Ramanujam (a tehsildar) camped at the village for years. They often conducted political classes for the villagers and instilled the ideologies of communist leaders and Periyar,” Vasu says.

It was these teachings that made the villagers mount a struggle to change the original name of their village–Sakkilipatti. They found it offensive since it originated from Sakkiliyar, a caste name.

“In the 1990s, we staged multiple protests to change the name to Stalin Puram after Joseph Stalin. But as there was not enough support, it was changed to S Patti,” Vasu adds.

According to Vasu, he and others don’t just extend help to someone from their own village marrying outside their caste, but anyone and everyone irrespective of their caste, social status, or the village and district they come from.

“There are several instances when we have crowdfunded to support intercaste couples who sought refuge here in the village and provided them legal assistance to deal with cases filed against them by their parents. If the couples are willing to live together and it is within the limits of the law, we are ready to go to any extent to support them,” he smiles.

However, the bonhomie that comes naturally to Vasu and others in S Patti is missing from another village not too far away.

A story of hate, 40 km away

Just 40 km from S Patti is Natham Colony, infamous for the 2012 Dharmapuri violence that started after a Dalit youth, E Ilavarasan, married a Vanniyar girl, N Divya. In the aftermath, Divya’s father committed suicide. Seeking revenge, Vanniyar community members burnt down 268 Dalit houses in Natham Colony and two adjoining villages in the district. A few months after her father’s suicide, Divya returned to her family and disowned her marriage. Ilavarasan, on the other hand, was found dead near a railway track a day after Divya’s return. At the time it was alleged to be a case of death by suicide, which his family contested.

However, things were not so grim always.

“Earlier, there were quite a few intercaste couples living in our village. As our colony is surrounded by people belonging to other castes, especially Vanniyars, we used to work in their fields as helpers. In fact, we used to share a good rapport with them. They used to visit our houses and have food with us. When we would go to their place, they would give us water in their utensils… we were treated like equals,” says S Kanaka, 39, a Dalit villager.

But everything changed after the 2012 incident. “These days, even though they walk through our lanes, most of them do not look at us. On rare occasions, a few of them, who were very close to us and not involved in the incident, exchange pleasantries. But nothing more than that,” Kanaka says.

Until a few years ago, she adds, they had completely stopped giving work to the Dalits choosing instead to do it all on their own. “It is only now that they are calling a handful of us for work under unavoidable situations. Even then, they don’t speak to us beyond a word or two.”

That [Ilavaran and Divya’s] was the last intercaste marriage in the village, says another villager, Saraswathi, 42. “We have strictly told our children not to fall in love with anyone outside our caste. We constantly remind them of that horror and how the entire community was punished for no fault of ours.”

After the 2012 violence, she adds, no one dared to fall in love with people from other castes.

Back in S Patti, young couples like Vasuki and Gopal can’t thank their stars enough. “It sometimes gets lonely and depressing… the realisation that they no longer accept your existence,” Gopal says.

It is during such lonely hours that the couple looks for support from the village elders in their new home. “To make us feel comfortable, they often visit our house and share their love stories.” Gopal hopes to share their story someday with some other young couple to make them believe that “love eventually finds a way”.