- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How the poor and backward battle a skewed higher education system

Thousands of youths from backward and marginalised communities are waging many battles on the financial, social and political fronts to access higher education.

Kaushal Kumar, 24, a second-year MPhil student at a deemed university in Mumbai, runs the risk of discontinuing his studies. For, he has to pay ₹61,000 fees for this year and ₹25,000 dues of last year before August 31. Although the university may give him some time and he can avail a concession of ₹4,000 available for the economically weaker section, he still has to pay the...

Kaushal Kumar, 24, a second-year MPhil student at a deemed university in Mumbai, runs the risk of discontinuing his studies. For, he has to pay ₹61,000 fees for this year and ₹25,000 dues of last year before August 31.

Although the university may give him some time and he can avail a concession of ₹4,000 available for the economically weaker section, he still has to pay the rest.

Hailing from a small village, Har Singh Pur in Etah, about 280 km from Uttar Pradesh’s capital, Lucknow, Kumar has come a long way in his career. In his village, higher studies are considered a waste of time, and not many study beyond class 12 or at the most graduation.

“After finishing graduation, many prepare for the police or army jobs. They do not aim higher, not because they lack ambition, but because of lack of information and financial constraints,” Kumar says. “They never think beyond graduation. People share newspapers in the village but it is common to miss out on university ads that appear in some corner of it.”

Kaushal’s father worked as a security guard in Noida and sold some odd items on a bicycle. Kumar, in his early years, took to selling milk in bottles. “When other kids from affluent families were out playing, we studied at home during day time as we had no lights to study at night. And when the village got electrified, we ran the risk of being falsely charged by upper caste people (Yadavs-OBC) with power thefts,” he says. It was only when he was in college that they got continuous electricity supply.

Later, he and his brother, who has two MA degrees, worked in a newspaper as ad agents. When he wanted to pursue Masters, getting into top universities in the country was an impossibility as he could not speak good English. In fact, the MPhil in women’s studies that he got admitted into and is pursuing now, is because the interviewers agreed to his speaking in Hindi, he says.

Widening gap

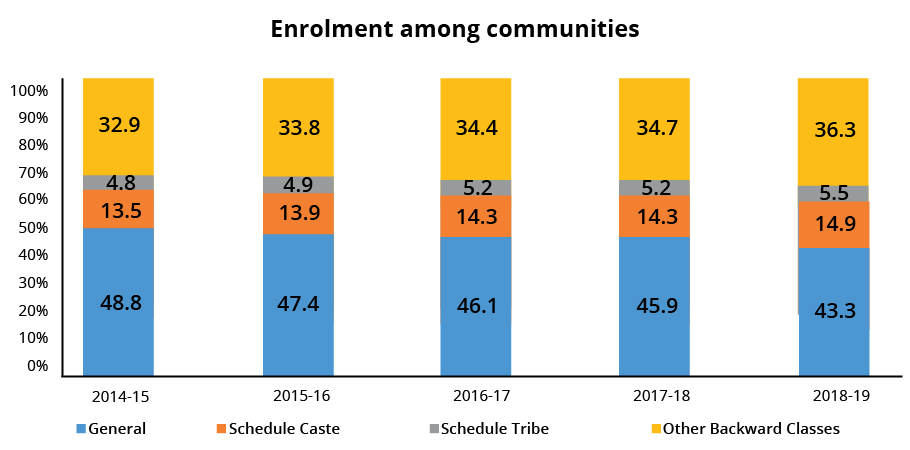

Kaushal is among the thousands of youths from backward and marginalised communities who are waging many battles on the financial, social and political fronts to access higher education despite a massive government funding, which is largely seen to be benefiting students from well-off, urban middle class families.

A 2019 report on the status of higher education based on income and regional profile by the Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC), Bangalore, indicates that the government’s higher education expenditure has extensively benefitted the richest income group compared to the poorest in the country. Similarly, the benefits were skewed towards students from urban areas than rural places.

“Income appears to be one of the important factors influencing the decision of rural households in pursuing higher education. There is an unwillingness of rural poor to afford the burden of direct and indirect cost of higher education. On the contrary, the urban population is willing to spend. It is mainly led by the urban middle class,” the report, which covers data (NSSO and higher education expenditure) for two decades between 1994 and 2014, said.

Uneven socio-economic conditions and the absence of concrete policy measures have in a way caused unequal participation of various segments of the population in higher education.

Despite the skewed participation, India, which has the second-largest higher educational system in the world after China — with 993 universities, 39,931 colleges and 10,725 standalone institutions — does not have even one institution in the top 300 universities in the world, as per UK-based Times Higher Education (THE).

The country’s top-ranked university, Bangalore’s Indian Institute of Science (IISc), which used to be in the 251-300 bracket for several years, dropped by 50 ranks to the 301-350 cohort.

A personal battle

The country’s expenditure on higher education as a percentage of its total budget has remained largely stagnant for nearly a decade at around 1.47%. This, despite the fact that India has the world’s largest population of young people aged 15 to 24, (241 million estimated).

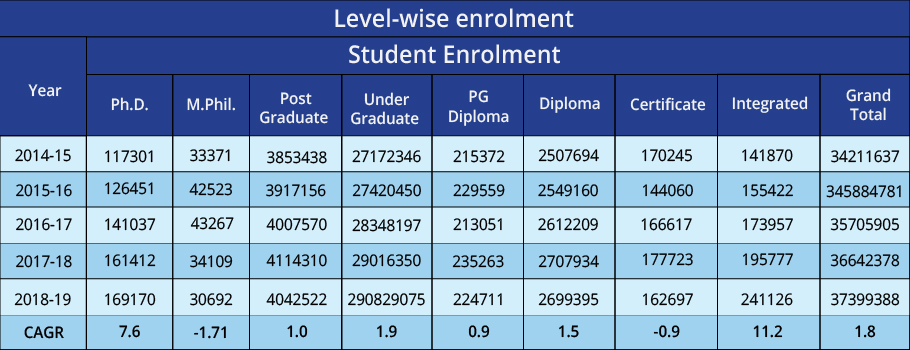

Even though India recorded a gross enrolment ratio (GER) of 26.3% in 2018-19, the share of Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe communities was quite low.

The current education system puts undue pressure on students to depend on parents or take up part-time work, which sometimes takes away their research or study time. With some of the prestigious educational institutions located in prime cities, the rent and food cost is an added burden, especially for students from rural areas.

Besides the financial constraint, many claim, mental harassment and suppression of dissent are other pressures that students from poor and backward communities are made to face.

A PhD scholar at Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi Vishwavidyalaya (MGAHV), who hails from a Scheduled Tribe and is also a gold medallist in MPhil, says he applied for transfer to Allahabad University after the college administration mounted pressure on him to transfer some of his research and scholarships funds for college activities, which he declined. He had posted a video on Facebook and shot letters to higher authorities, which angered the administration.

Coming from a tribal community, such hurdles weakened his interest. “For how long will one keep struggling and fighting? The administration should respect and offer equal opportunity for the rural poor,” says the student who wished to remain anonymous because the university hasn’t granted him a transfer certificate yet.

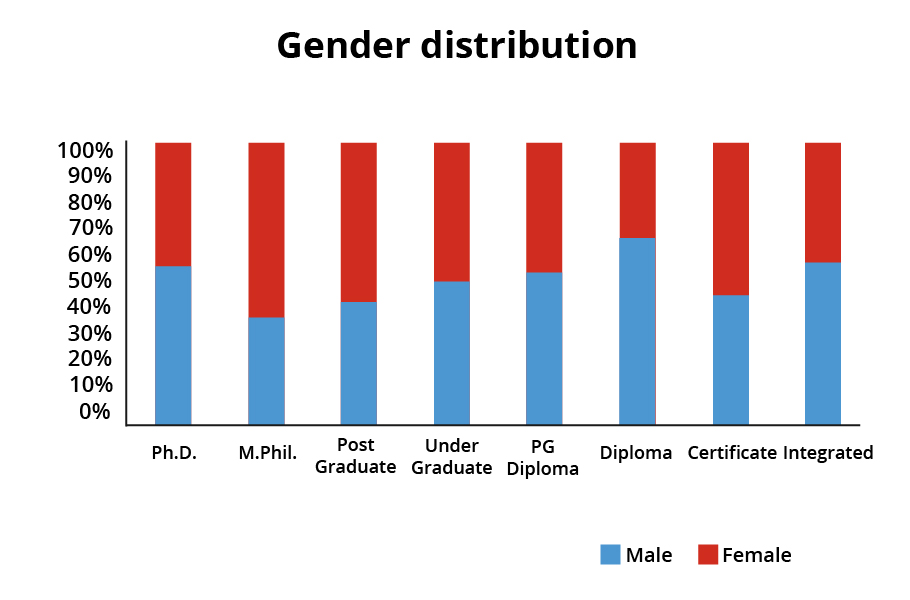

Gender disparity

The ISEC report highlights that access to higher education is biased towards male, with the gap more prominent among the poorest income groups. In urban India, however, it presents a different picture, where a fair degree of encouragement is shown towards female education among the middle class, indicating a shift from stereotypical thinking.

Further, Prof Karnam Gayithri of ISEC who co-authored the paper, notes that the gender disparity in higher education campuses is unfavourably skewed against rural women.

While educating girls, particularly for higher studies, is accorded a lower priority in Indian families, girls passionate about it are largely left to fend for themselves, even while battling societal norms.

Dipti, 27, a performing arts (theatre) student belonging to Scheduled Caste, is hoping to enrol for a PhD in Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi Vishwavidyalaya (MGAHV), Wardha, to do research on theatre.

She prefers the college as it is an overnight journey from her hometown in Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh, and anything further away would attract strong disapproval from her family members.

Managing home, assuring parents of her safety, dealing with her finances, juggling part-time jobs and studying, are just everyday problems for her.

At her age, the pressure of marriage is yet another concern. “My parents wonder sometimes that if I study more, I may not get a good groom. So they mildly put it that I should stop studying further,” she says.

And yet, she’s the first in her family to scale this height. “Being a woman belonging to SC, and coming from a place like Chhattisgarh, I feel it’s been a long struggle to reach this level,” she says.

Although she lost a year after her MPhil, having failed to enrol in a private institution, she aims to get into a government university so that her education expenditure isn’t high. For her, asking for money from her parents, at the age of 27, is not a situation she would like to put herself in.

Dipti, whose father is a lower rung employee in the municipal corporation, is now saving for her higher studies by selling her artwork, besides looking for financial aid.

Free higher education?

She feels that if the government provides free (higher) education, it would certainly help a lot of women, particularly those coming from poor socio-economic backgrounds, to study further.

But initiatives in this direction are lacking on the government’s part. The HRD ministry too has said in the Lok Sabha that the University Grants Commission (UGC) has no plans to launch any new scholarship scheme to promote higher education.

For many students who depend on fellowships and aid for higher education, taking a bank loan is not an option. They fear getting into a debt trap.

Again, there is little help from the government. The National Backward Classes Finance & Development Corporation (NBCFDC) and National Scheduled Castes Finance and Development Corporation (NSFDC) — a government undertaking under the aegis of the Ministry of Social Justice — do not provide higher education loans at zero interest to SC and OBC students.

Prof Ram Shankar Kureel, former founder vice-chancellor of Baba Saheb Ambedkar University of Social Sciences in Madhya Pradesh says while free higher education will benefit students coming from poor backgrounds, he’s not sure if the present government would do that. Also, he says regulating fee structure of private universities will be difficult.

Kureel, who was part of the K Kasturirangan committee on National Education Policy says several recommendations to that effect has already been submitted to the authorities and it is up to the proposed National Higher Education Regulatory Authority (NHERA) — to be headed by the Prime Minister and three others — to decide.

Prof Gayithri of ISEC, however, notes that the expansion of public higher education has begun to provide egalitarian opportunities to the poor, though rather slowly. “Any effort towards curtailing its expansion would lead to a humongous loss for the poor,” she adds.

Fighting their way out amid COVID

The COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown has only worsened the condition of students like Dipti and Kaushal as they face difficulty in paying fees. With the crisis affecting the job markets, even students who wish to go for paid-internships, summer-jobs, part-time works, struggle to find a footing. With parents losing jobs or facing pay cuts, students dependent on them to continue higher studies, too, are facing hardships.

But for people like Kaushal, who took up women’s studies that looks at gender atrocities over the years, higher education is not just an avenue to get a better job, but also a means to wriggle out of backwardness.

“Going up the ladder in education taught me to fight for my rights. But if the financial pressure is not eased on students, many will lose out,” Kaushal says.

Providing free higher education, he adds, should not be seen (by the government) as a burden.