- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How the humble PCO booth saved many a job and heartbreak

When Chennai-based banker Aparna Bera was growing up in her hometown Kolkata, there were many small booths painted in bright yellow that randomly dotted the lane leading to her house. She had often seen people cramming the booths as they waited for their turn. There also used to be one ‘lucky’ caller inside a tiny cabin, almost always lost in a deep conversation, with just a...

When Chennai-based banker Aparna Bera was growing up in her hometown Kolkata, there were many small booths painted in bright yellow that randomly dotted the lane leading to her house. She had often seen people cramming the booths as they waited for their turn. There also used to be one ‘lucky’ caller inside a tiny cabin, almost always lost in a deep conversation, with just a glass door separating his world from the rest.

By the time Aparna was a grown woman, the booths were no longer crowded, the glass-fronted cabin mostly vacant. Rather, everyone started carrying their own PCO in the pocket — the much-prized mobile phone. Both handsets and mobile tariffs had become dirt cheap.

It wasn’t until the summer of 2015 that Aparna thought she would ever miss the sight of those booths. Then a 33-year-old, Aparna was travelling from Chennai to the Union Bank of India’s regional office in Bibikulam, Madurai, on a bus for an important meeting. She suddenly realised her smartphone had ran out of battery. Aparna had spent the roughly eight-hour bus journey working on a presentation so even her laptop’s battery had drained out. To top things off, the bus was delayed. With no phone, no laptop, she started panicking. “We are so dependent on our smartphone for directions and booking cabs that we cannot imagine travelling to a new location without it,” Aparna recalls the incident.

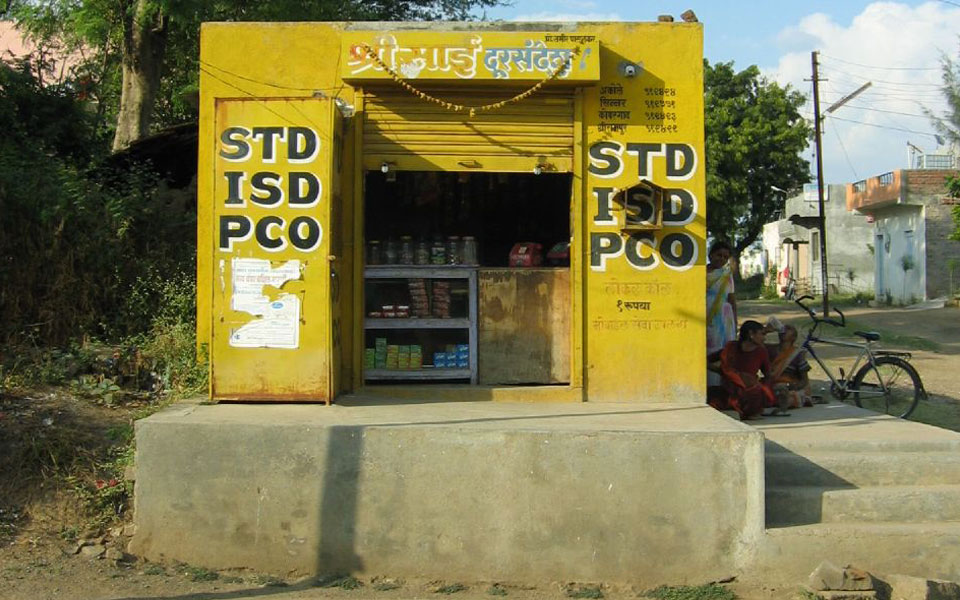

As the bus stopped at its destination, a nervous Aparna didn’t know who to reach out to and how until her eyes saw a yellow wall with ‘ISD, STD, PCO’ written in bold black letters. “The sight of the yellow walls brought me immediate relief. I informed the manager about my delay and the meeting was postponed by a couple of hours,” says Aparna.

Aparna’s moment of relief, in a way, defines the success of Sam Pitroda’s vision to paint PCOs in bright yellow so that people know that a public phone is around. Pitroda, who is credited for transforming the face of India’s telecom sector, was the brains behind the Centre for Development of Telematics (C Dot), established in 1984. C Dot ensured that STD/PCO/ISD booths were present in every nook and corner of the country.

Recalling his experience in his book, Dreaming Big: My Journey to Connect India, Pitroda writes that the yellow booth was designed to stand out in the same way the red British telephone booths did.

The STD booths/PCOs have now become a last resort for people stuck in situations similar to Aparna’s. However, nearly three decades ago, these ubiquitous booths were witness to many a reunion of friends and families, budding romances — bridging all geographical distances through the wires. But most importantly, the idea of PCOs/STD booths also meant jobs to many unemployed youths.

“The idea was not just to make phones accessible but also to employ a large number of people. We instituted a policy that gave job preference to people with disabilities,” Pitroda writes in his book. During its peak days, around two lakh disabled people were employed in nearly 60,000 STD/PCOs booths across the country, as per government data.

In the early 1990s, 44-year-old Suresh Padmanabhan and his family of four stepped out for a walk every weekend after dinner. The destination was always the same — an STD booth.

The entire family scooched inside the narrow booth and called their relatives one after the other. “In the first couple of minutes, our parents would speak to their relatives about their whereabouts and then pass the receiver to us to quickly say ‘hello’ to our aunts, uncles and cousins,” Padmanabhan says.

Nowadays, you can speak to people over a call for hours, but it was not the case back then, says Padmanabhan, who is now a Railways employee in Chennai. “Our parents used to keep track of time when speaking to people as calls were an expensive affair. We usually went to the booth late at night as the charges were halved after 10 pm,” he adds.

One had to pay ₹2 for a one-minute call within India for the first five minutes. The charge doubled after that.

“The PCO booths, which are often deserted now, used to be a popular destination. Every now and then, you could spot a long queue outside booths, often yelling at the person inside for taking so much time,” Padmanabhan recalls.

Padmanabhan is not alone who now talks of PCOs in the past tense. But are these booths really dead?

The 20-year-old STD/PCO booth at the Dadar railway station in Mumbai tells as different tale. The booth continues to attract 800-900 customers every day, according to an Indian Express report published in 2018. The customers include long-distance commuters who may be without a mobile phone, regulars who call their families, and lovers who talk for nearly an hour.

The public call office (PCO), subscriber trunk dialling (STD) and international subscriber dialling (ISD) booths, introduced in the early 1990s, changed the lives of millions of Indians. The booths connected people across India and overseas giving them relief and an opportunity to contact their families back home.

Growing up, Naseeb Khan spent most of his summer holidays at his grandmother’s place in Beleghata, a village in Kolkata. His parents worked at an auto company in Bengaluru, and STDs were the fastest mode of communication.

Recalling one such summer vacation in 1996, the 45-year-old says that back then the PCO owner of his street would come to his grandmother’s house and inform her to come to the shop at a particular time when his father would call. The owner charged an additional ₹10 for informing them.

Khan and his grandmother would get ready and wait outside the PCO for the call. Sometimes the wait was long but it was the only way for his grandmother to talk to her son. “I still remember the sigh of relief that covered my grandmother’s face every time she heard her son on the other end of the phone,” he says.

In just a few years, the public phones made inroads into almost every street across India. Government data shows that PCOs grew from 1.97 lakh in 1994 to a peak of nearly 60 lakh in 2008. And the more streets it invaded, the more imprints it left behind in the lives of people.

Deepak Bhagat of Bano, a village roughly 100 km from Ranchi in Jharkhand, is one of the many who grew up with phone booths as an essential part of their lives.

The 28-year-old, now an electrical engineer, grew up dialling phone numbers for older and uneducated people who walked into the small STD booth that housed two receivers and a billing machine. The shop became a means of earning a living for the family.

In a couple of years, the demand increased and Bhagat’s family installed a payphone where you could just enter a ₹1 coin and talk for a minute. “I used to do my homework and manage all the callers. Sometimes, I used to talk to customers while a phone gets free,” he says.

As the number of booths increased, people also started using it to make prank calls. With time, some started using PCOs for extortion and threats. As a result, in 2012, the police issued instructions to all STD and PCO operators to check the identity of callers before allowing them to make phone calls.

“We maintained daily call logs of the people in a register in hopes that we could provide the identity of the caller if ever the police came for enquiry. It contained the phone number to which the call was made, the duration and the amount,” Bhagat says.

The yellow revolution or the PCO boom, however, was short-lived as mobile phones came in between 2005 and 2010. The number of PCOs across the country started declining for the first time in 2009. The PCO count across the country dipped by 4.6 lakh from 59.8 lakh in 2008 to 55.2 lakh in 2009, according to the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India.

As a result, the number of customers who came to Bhagat’s shop declined. “After mobile phones came in, there were hardly 10 to 15 customers throughout the day.” Bhagat, and many like him, slowly cleared receivers from their shops and started selling SIM cards, chargers and stationery.

In 2013, the government officially permitted the existing STD/PCO booth holders to sell mobile phone recharge coupons, new SIM cards (new connections), mobile phones and related accessories against an additional license fee to enhance the viability of the shops.

As mobile phones became cheaper, the number of STD/PCO booths across the country recorded a sharp dip. There were just 5.6 lakh public call booths across India, the minister of Communications and Information Technology Ravi Shankar Prasad informed the Parliament in August 2015.

Some owners, however, continue to run STD/PCO booths so that they can come to the rescue of commuters like Aparna, whose phone battery died in an unknown city.

“Nowadays people come here only when their phone switches off, or when they don’t have balance. I keep my shop open because I know it helps people when there is no other way to communicate,” says Mohan Sundararam, who has a STD/PCO booth in Kasturba Nagar, Adyar, in Chennai.

But what Sundararam finds amusing is that many people who come to his shop now don’t remember phone numbers. In the age of technology where people have smartphones, the need to remember phone numbers has come down drastically.

In the 1990s, Aparna says that her parents made her memorise their contact numbers so that she could call them in case of an emergency. “I still remember my parents’ contact numbers. It is because I had memorised them when I was young and they still use the same numbers.”

Over the past decade, it has become harder to spot public booths but shopkeepers like Sundararam still hold the ISD, STD, PCO banner high, offering us a chance to take a walk down memory lane.