- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How the Chalukyas and Rashtrakutas shaped south India

The medieval Deccan is a region of geopolitical wonders. Over nearly 500 years, the region undertook some of the world’s most stupendous architectural achievements and traded with the world to the point where it was considered among the global great superpowers. But only a few know about the history of the region and its rulers. Anirudh Kanisetti, author of the recently released book, Lords...

The medieval Deccan is a region of geopolitical wonders. Over nearly 500 years, the region undertook some of the world’s most stupendous architectural achievements and traded with the world to the point where it was considered among the global great superpowers. But only a few know about the history of the region and its rulers. Anirudh Kanisetti, author of the recently released book, Lords of the Deccan: Southern India from the Chalukyas to the Cholas, uses a range of historical and archaeological sources to show that the Chalukya and Rashtrakuta dynasties of the Deccan had a profound impact on shaping the history of the subcontinent.

The story begins in the 6th Century — decades after the collapse of the western Roman empire in Europe and only a few years after the disintegration of the Gupta empire in northern India — when the clan of Pulakeshin-1, the founder of Chalukya line, had set up their primary capital at the great fortified citadel of Vatapi (today’s Badami in Karnataka) by 543 CE. In Lords of the Deccan, Kanisetti discusses how the Deccan innovated in the fields of culture, art, language, and trade, and how it influenced the trajectories of many modern Indian states. “The Deccan is a vast, unique and fascinating landmass that doesn’t get its due in either Indian or global history. My interest in it started because I am Deccani myself and barely knew anything about it: I wanted to learn more about my motherland, and as I did, I wanted to tell its stories to the world,” said Anirudh, while speaking about why he brought out a 471-page well-researched book on Deccan, the entire southern peninsula of India, south of the Narmada River.

This region is very often thought of only as a bridge between north and south India but nothing could be farther from the truth. The Deccan is two-thirds the size of Iran and roughly the size of Germany, and is many times more populous. “It (Deccan) has been home to some of the most influential religions in human history, such as Virashaivism, as well as mighty empires such as those of the Chalukyas and Rashtrakutas, who were the direct predecessors of the Kakatiyas and other dynasties who are better known today. It has been deeply connected to global movements of people and ideas and has shaped India’s history on its own terms. Between the 6th and the 12th century AD, it was the dominant power of the Indian subcontinent and directly influenced the way we all live today,” he said.

Anirudh’s Lords of the Deccan, published by Juggernaut Books, is focused on telling the story of the medieval Deccan to those who may have no familiarity with it, especially younger people. “In an age where misconceptions about history are commonplace, I wanted my narrative to be based on hard historical facts and critical research, while simultaneously showing the reader how the process of history writing works and giving them an insight into the workings of political power. I wanted to do all this while making sure the vibrant reality of history — the drama, the violence, the opulence, sophistication, and humanity of my protagonists — shone through and kept the reader hooked as they explored this world with me,” he said.

Anirudh said it has been very heart-warming to see that many readers, including senior scholars and academics, appreciate the book for all these reasons. “Younger people especially have been very excited to learn more about Deccan and South Indian history and I’m excited because there are so many more stories to bring to life for them,” he added.

Since KA Nilakantha Sastri’s A History of South India, first published in the 1930s, there have been very few scholarly books written for a general audience. Academics have made some remarkable advances in the decades since, though these discoveries have been mostly written for and focused on a scholarly audience. “I critically fused the work of Prof Sastri and others with the research of more recent scholars, all while experimenting with various narrative forms. I also spent considerable time looking through archival materials, especially epigraphical sources, to try and build the narrative and obtain details about the culture and minds of the rulers of the time — this research helped bring to life their devastating wars, especially those of the Chalukyas and Cholas in the 11th century CE,” said Anirudh, who is an editor at the Museum of Art of Photography, Bengaluru.

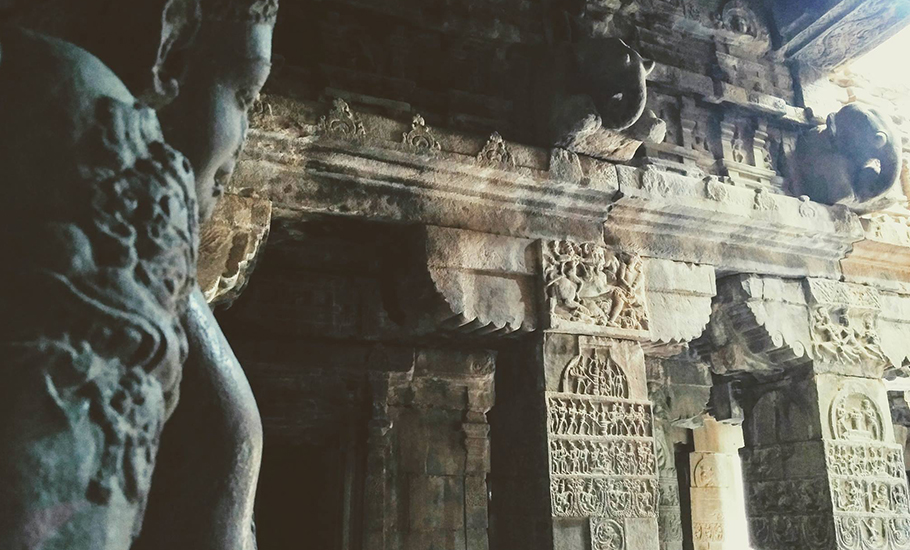

The history of Deccan is nothing without its temples. However, there is a story behind these architectural marvels. “Today, it is difficult to imagine Hinduism without temples. That was not the case during the time of the early Chalukyas. Then the idea of building permanent shrines for ‘Hindu’ gods was somewhat of an innovation. Buddhists, on the other hand, were used to worshipping idols and congregating around permanent religious institutions such as monasteries or stupas, and folk religion in the subcontinent always had a strong idol-based aspect to its worship of yakshas and other fertility deities. But orthodox Hinduism, even up to the early centuries CE, had still relied primarily on vedic rituals. These rituals were performed in temporary altars, built specifically to perform a sacrifice and destroyed after,” writes Anirudh.

However, the practice changed during the 4th Century AD. Aided by the patronage of the Gupta emperors of northern India, Hindu cults adopted permanent iconic representations of gods and introduced radical technological innovations in a bid to increase popularity and capture patronage. “In the new, temple-based, Puranic Hinduism, gods such as Shiva and Vishnu were embodied as idols and were declared supreme. They no longer needed sacrifices to help them order the cosmos, but went about their business according to a plan that mortals could not hope to understand. Mortals could also bring them to earth as permanent residents in temples, not just as temporary visitors to sacrifices. There, they could propitiate these mighty deities with new rituals that were presented as reworked versions of Vedic sacrifices: periodic daily offerings of animals, food, flowers, and so on. This innovation proved popular with rich and poor alike. Royals across northern India soon started to build shrines for Hindu gods, while continuing their patronage of existing Buddhist and Jain institutions,” he added.

Orthodox Hinduism, even up to the early centuries CE, had still relied primarily on vedic rituals. These rituals were performed in temporary altars, built specifically to perform a sacrifice and destroyed after. — Anirudh Kanisetti

“The popularity of temple-based Hinduism also led to the gradual creation of new religious communities, more amenable to supporting the activities of warlike aristocrats who claimed a special relationship with the gods– all of which were in stark contrast to what Buddhists in south India were willing or able to offer,” writes Anirudh. Early Chalukya temples, in particular, according to Anirudh, show us how medieval kings used these buildings as a crucial aspect of their power. Chalukya temples are replete with subtle and not-so-subtle political messages.

The Chalukya emperors also adapted and reworked north Indian Sanskrit political propaganda to suit the Deccan, sparking off generations of imitations and a feverish era of Sanskrit literary production across southern India, he said. “The successors of the Chalukyas, the Rashtrakuta emperors, took a south Indian Sanskrit grammatical treatise and used it to create a grammar for Kannada, the language of the people of Karnataka, the heart of their empire. In doing so, they set off an explosion of regional literature that lasted off and on for a thousand years – the first time any vernacular language successfully challenged Sanskrit’s dominance of court culture. If not for their activity, it is doubtful that many south Indian languages (with the exception of Tamil) would have the hallowed literary tradition they now do,” he said.

It was a long and difficult process to polish the facts into a single cohesive narrative because the scope of the book was very ambitious — it took nearly four years from beginning to end, but it taught Anirudh a great deal as a historian and a writer. “It was truly awe-inspiring to see how deeply India influenced the world through my period of interest — I came across Buddhist bronzes which had been exported all the way to Sweden, references to Deccan kings in Arab texts, and so on. I’m glad I was able to weave all this together to show readers what an extraordinary time the medieval period really was,” said Anirudh.