- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

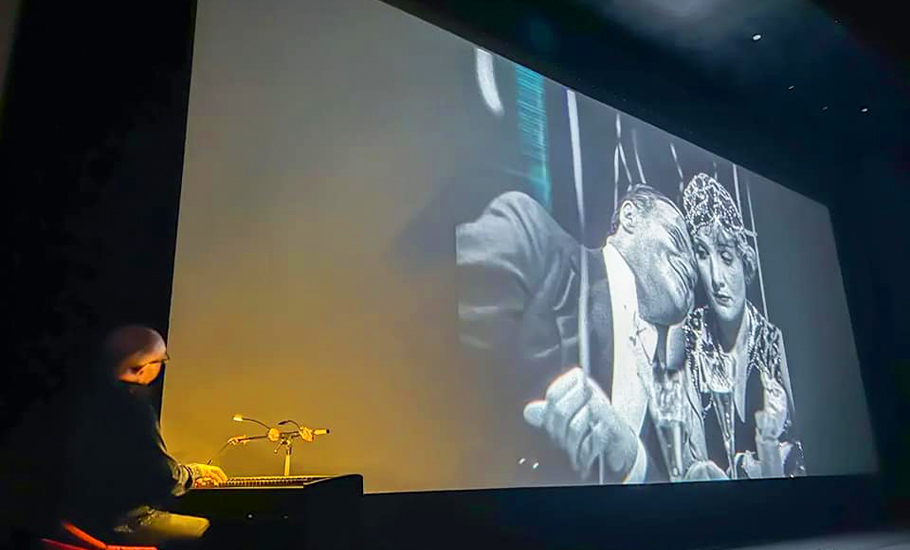

How silent films found a voice at the 27th International Film Festival of Kerala

In 1913, India’s first full-length feature film Raja Harishchandra was released in Mumbai. Directed by Dadasaheb Phalke, the silent film was based on the story of an honest king of the Ikshvaku dynasty. The country’s first talkie Alam Ara, directed by Ardeshir Irani, was released in 1931. More than 1,500 silent films were made between 1913 and 1931. However, the prints of only 31...

In 1913, India’s first full-length feature film Raja Harishchandra was released in Mumbai. Directed by Dadasaheb Phalke, the silent film was based on the story of an honest king of the Ikshvaku dynasty. The country’s first talkie Alam Ara, directed by Ardeshir Irani, was released in 1931. More than 1,500 silent films were made between 1913 and 1931. However, the prints of only 31 silent films survive today as the rest were lost to lack of care and maintenance.

Having once played an important role in the social and cultural spaces across the world, silent movies have been relegated to a silent oblivion today. However, renowned pianist Jonny Best recently showed how silent movies cannot only be revived but can also be given a voice of their own.

Jonny Best played his piano while watching five 100-year-old year old silent films with the audience, screened on consecutive days as part of the recently held 27th International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK) at Tagore Theatre in Thiruvananthapuram. The silent movies include FW Murnau’s Nosferatu, Erich von Stroheim’s Foolish Wives, Curtis Bernhardt’s The Woman Men Yearn For, Victor Sjöström’s The Phantom Carriage and Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Parson’s Widow.

As a pianist, Best specialises in improvisation and silent film accompaniment, working solo and with a variety of collaborators. “I am giving music to the scenes instantly, looking at the facial expression and actions of the characters in the movie. The challenging part is that the notations are instant. I have to create them based on the scenes. I know it is difficult but I love to do it as a tribute to these silent films,” said Best, who is the resident pianist at British Film Institute’s Southbank.

Best studied piano with veteran Polish pianist Ryszard Bakst at Chetham’s School of Music, and drama at University of London. But why does he provide live music to silent films?

“Most silent films don’t have accompanying music. So, my idea is to bring the film alive by providing music to it. Even though the notations are instant, I always try to get an idea of the film before I play live music with it,” he said. “The combination of music and storytelling has run through my career ever since as I’ve moved between working in theatre, musical theatre, opera, orchestral music, arts festivals and film,” he said.

In 2022, Best completed his PhD research at University of Huddersfield Music Department, which focuses on silent film piano improvisation. “I am interested in the pedagogies of improvisation. As well as teaching the improvisation module at University of Huddersfield for three years, I regularly lead practical improvisation projects with young musicians, and masterclasses with improvisers at all levels. I also have a collaborative artistic research practice with violinist and fellow PhD researcher, Irine Rosnes, with whom I regularly perform improvised silent film accompaniments,” he said.

The experiment evoked tremendous response, particularly when Best played piano during the screening of FW Murnau’s horror silent movie Nosferatu (1922). “Live music gives a sense of liberation. I have to change the music according to the situations. The music varies from comedy to horror. Playing tunes to the changing emotions is challenging,” said Best.

Those who got a treat of Best’s unique experiment thoroughly enjoyed it. “I have watched silent films before but this is the first time I could watch it with live music. It’s a great experience,” said S Krishna Kumar, a delegate at the IFFK.

While Best focused on the improvisation of silent film viewing, renowned German filmmaker-writer Veit Helmer spoke about the importance of (film) restoration. “We have advanced technology today, but restoration (of films) is time consuming. Not many in the film field care about restoration. We have lost the original prints of many great films. Restoration is challenging, but we need to think about it seriously,” said Helmer, whose feature films Tuvalu (1999), Absurdistan (2008) and The Bra (2018) won accolades at various international film festivals.

To prove his point, Veit Helmer narrated an incident that occurred when he tried to restore the print of Bratan ((1991), directed by Tajikistan-based filmmaker Bakhtyar Khudojnazarov), from the Russian government. Bratan was one of the last movies made before the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

“Khudojnazarov was a great friend. He made Bratan when he was barely 25 years of age. He died in 2015. The copies of Khudojnazarov’s films, particularly Bratan, were not available. I approached some film officials in Russia. They asked money for scanning the negatives. I paid for them and brought the copies to Germany where I restored Bratan. I spent a lot of time on the restoration of this movie but that’s what restoration is all about,” he said. Helmer screened the 35mm restored version of the lost 35mm print at the Venice Film Festival in 2019.

The films are accessible today, thanks to digital advancement. However, there are a lot of classics to be restored, particularly analogue films, which tend to fade after some time. “If you want to introduce these classics to the present generation, then you have to act fast. We need to act fast if we want to save the heritage of the films. When you restore a movie, you make sure that it is available somewhere in the world. We have highly advanced digital technology. The advantage of it is that the colour never fades in the digital format unlike the analogue films,” said Helmer, while speaking on “Significance of Film Restoration and Archival” in a session conducted as part of the 27th IFFK at Sree Theatre in Thiruvananthapuram.

Even though restoration is important, Helmer said, ‘it should be based on certain ethics.” “Restoration doesn’t mean recreation. It doesn’t mean converting a black and white movie to colour. A black and white movie should never be converted to a colour format. It is a kind of artistic murder,” he said.

In developed countries, the government takes care of the restoration of films. “Scanning is the first step of any film restoration. So you can scan it and keep. Whenever you get the funding, you can restore the movie. Otherwise, you will lose the negatives due to ageing,” said Helmer.