- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How Sankaradas Swamigal shaped Tamil theatre before being ‘forced’ to leave it

It is hard to find any Tamil film enthusiast who hasn’t heard the song ‘Gnana Palathai Pizhinthu’ from the 1965 film Thiruvilaiyadal. Unfortunately, it is equally difficult to find anyone who knows the lyricist behind the song so deeply rooted in Tamil cultural milieu. The song, beautifully sung by renowned KB Sundarambal, was actually penned by Sankaradas Swamigal, considered to...

It is hard to find any Tamil film enthusiast who hasn’t heard the song ‘Gnana Palathai Pizhinthu’ from the 1965 film Thiruvilaiyadal. Unfortunately, it is equally difficult to find anyone who knows the lyricist behind the song so deeply rooted in Tamil cultural milieu.

The song, beautifully sung by renowned KB Sundarambal, was actually penned by Sankaradas Swamigal, considered to be the ‘Father of Tamil Theatre’. What adds to this saga of neglect is that it also remains forgotten that successful films such as Valli Thirumanam, Pavalakkodi, Sathyavan Savithri, Alli Arjuna, Nallathangal and Gnanasoundari were actually inspired by plays written by Swamigal, whose death centenary year is being observed in 2022.

But the man, who gave theatre so much, eventually went on to renounce acting in theatre as women suffered miscarriages and even death after seeing his powerful and intense acting.

“At a time when Tamil Nadu was oblivious to formal theatre tradition, Sankaradas Swamigal had not only written 40 plays but also staged them. The themes of his plays were based on common people. He wrote his plays keeping regular people in mind,” said veteran communist leader P Jeevanandam during a lecture he gave in 1958, in Puducherry.

The significance of Swamigal as a modern dramatist is best underlined in the Encyclopaedia of Tamil Literature (1990) Volume 1, which says he brought about a creative blend of the old and the new in the Tamil dramatic tradition.

“He [Swamigal] has fused into his plays the elements of the ancient folk dramatic forms, those of the musical plays of the pre-modern days, and the characteristics of the modern Tamil play that came into being under the impact of the West,” it said.

To trace Swamigal’s journey, it is important to trace the journey of Tamil theatre itself.

Evolution of Tamil Theatre

Inscriptions found on stones in many temples across Tamil Nadu suggest that the Tamil theatrical tradition has existed since time immemorial. The Tamil language has itself, in ancient times, been divided into three components—iyal (poetry), isai (music) and natakam (drama). In ancient times, theatre was mostly performed in villages, by villagers, for villagers.

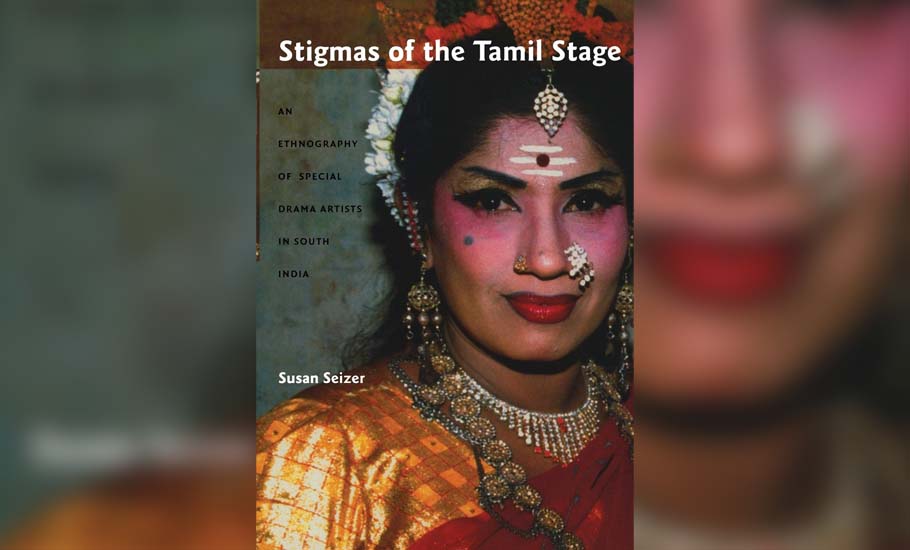

Writing in her book Stigmas of the Tamil Stage, anthropologist Susan Seizer arrives at the conclusion that Tamil drama history has undergone four stages. She says that during the first stage, “A separate tradition of folklore plays in verse and song is documented in extant seventeenth and eighteenth century texts though it is unclear to what extent these are continuous with popular indigenous Tamil folk theatre as it appears today.”

She argues that before Western influence on Tamil popular theatre started to show, “Dramatic performances had been the prerogative of a limited number of (caste) lineages, whose members held locality-specific rights-cum-obligations to perform on particular occasions.”

“This system defined Tamil theatre until the mid-19th century.”

The second stage began in the 1860s with Tamil scholars who hailed from the elite class. They translated and adapted Western dramas and literature for a niche elite audience.

“The elitist character of the plays stems from their [authors] anxiety to ‘raise’ Tamil drama to the level of the Sanskrit and the Western plays. This was considered the beginning of ‘modern’ Tamil plays, defined as such precisely because they were based on Western models. At this stage, involvement in theatre came to be considered by the elite to be a fit engagement for people with Western education,” writes Seizer.

At stage three, according to Seizer, Parsi drama troupes from Bombay travelled to Tamil Nadu and performed plays on Puranic and court themes that incorporated stage conventions adopted from the West.

“These companies charged admission fee from the audience and are said to be responsible for the beginning of commercial theatre in India. In Parsi companies, the paid employees, including actors, were more disadvantaged in education and economic status than company owners. This established what was to become a class hierarchy in the organisation of commercial theatrical companies across the country,” said Seizer.

During the fourth stage, Seizer writes that Tamil drama companies developed along the Parsi model, incorporating both indigenous Tamil material content and the stylistic influences of Western theatre made familiar by Parsi troupes.

“Of the new Tamil drama companies, the two most influential were begun by Pammal Sambanda Mudaliyar, a member of the judicial service, in 1891, and Sankaradas Swamigal in 1910. These two companies also inaugurated the split of modern Tamil theatre into its two separate streams—the former, the world of elite amateur drama sabhas and the latter of professional, commercial popular theatre,” Seizer said.

The arrival of Sankaradas Swamigal into the theatrical scene in 1891 marked the era of modernising Tamil theatre in its entirety. Swamigal established his own drama company in 1910.

From Kattunaickenpatti to Karuvadikuppam

Thoothukudi Thamothara Sankaradas Swamigal was born on September 7, 1867, to Thamothara Thevar and Pechiyammal at Kattunaickenpatti, a village in Thoothukudi district. Sankaran was his maiden name.

His father was a well-respected Tamil scholar and used to give lectures on Ramayana earning the title of ‘Ramayana Pulavar’. Sankaran got his primary education from his father. He started working early in life as an accountant at a salt company. At that time, for Sankaran just like most other people, watching drama was the only form of entertainment available.

Sankaran had a knack for writing poems since childhood. By the time he turned 16, he was writing poems based on various poetic meters such as Venba and Kalithurai. In his twenties, Sankaran learnt Tamil literature and grammar from Palani Thandapani Swamigal. Well-known poet Udumalai Muthusamy Kavirayar was his classmate then. When Sankaran entered into theatre, he was just 24.

It was in his book Thandapani Pathigam that Sankaran penned the lyrics of the song ‘Gnana Palathai Pizhinthu’. The song was later used by veteran filmmaker AP Nagarajan in his film Thiruvilaiyadal. Besides writing poems, Sankaran was well-versed in Tamil ancient music, folk music and religious texts such as Thevaram. During his student days, Sankaran had helped a Christian missionary, Edward Paul, who wanted to compose songs on Jesus Christ in Tamil.

“While Paul sung songs based on English notes to give an idea to Sankaradas Swamigal about how the songs should be composed, Swamigal absorbed the ideas and wrote songs in Tamil based on those notes. This is how Swamigal also had a brush with Western music and later used that knowledge in many of his plays,” writes K Parthibaraja, a well-known theatre artist who has authored a book on Sankaradas Swamigal titled Saame that was published in 2021.

Swamigal also learnt Hindustani music from Gulam Muhammed Abbas, a Hindustani music virtuoso, adds Parthibaraja.

The literary and musical training that Swamigal received drew him to the world of theatre in 1891. According to Parthibaraja, Sankaran started working as an actor in Navarasa Alankara Nataka Sabha at first.

The unfortunate turn

“Then he wrote plays for Vannai Hindu Vinodha Sabha and while working for this company, Swamigal went to Sri Lanka to perform. He worked as a drama director in the company called Sri Krishna Gana Sabha. While he was working there, a series of unfortunate events pushed Swamigal out of the world of theatre. After a brief hiatus, Swamigal started working in companies such as Kanadu Kathan Vaidyanathaiyar Company and Shanmugananda Sabha,” says Parthibaraja.

As an actor, Swamigal played various negative characters found in Puranas such as Hiranyakashipu, Ravana, Lord Saneeswara and Lord Yamadharma among others. One day, in the village Nalatinpudur, near Kovilpatti in Thoothukkudi, Sankaran staged the play ‘Nala Damayanthi’. He played Lord Saneeswara. In those days, dramas used to be performed from night to the next morning. In the early hours of the next day, the play came to an end and Sankaran wanted to remove his makeup. He went to a nearby well located in the village.

“Swamigal had a well-built physique and good height. He had painted his body black for his character. A woman came there to fetch water from the same well where Swamigal was removing makeup. Seeing Sankara in Lord Saneeswara’s makeup, the woman got shocked and vomited blood that resulted in her death. This event pushed Swamigal to quit theatre,” writes Parthibaraja.

This was not the first time such an untoward incident happened in Swamigal’s life. Earlier during the play Sathyavan Savithri, while seeing him act as Yama, a pregnant woman had a miscarriage. In another play Prahalada, his acting as Hiranyakashipu saw a woman faint, Parthibaraja added.

Within a year of his entry into theatre, Sankaran decided to quit the field because of the repeated unfortunate incidents. By 25, he became a monk and went for pilgrimage to Kasi, Gaya and Kathirgamam in Sri Lanka. It was then that Sankaran became Sankaradas Swamigal. Due to the efforts of famous percussionist artist Manpoondia Pillai, Swamigal started to contribute to the theatre through his writing while refraining from acting.

Following a stroke, Swamigal’s health deteriorated and he died at Karuvadikuppam, a village in Puducherry, on November 13, 1922. The death centenary celebrations of Swamigal started in 2021.

“Swamigal wrote 68 plays in his lifetime, out of which only 16 were found in their entirety,” said Parthibaraja.

Special drama

One of the major contributions of Sankaradas Swamigal to Tamil theatre was ‘special drama’. According to Seizer, ‘special natakam’ (special drama) is a genre of popular Tamil theatre that began in the late 19th century.

“The name draws from the practice of hiring each artist ‘especially’ for each performance, thus making it a ‘special’ event. There are no troupes or companies in special acts. Each artist enters individual contracts for a given performance, often assisted in the booking process by drama ‘agents’. Equally remarkable is the fact that there are no rehearsals or directors for special drama. Artists may actually meet for the first time onstage. All this is made possible by a system of familiar repertory roles—hero, heroine, buffoon, dancer, and so on,” she writes.

Seizer added that Swamigal is much more than just a historical figure to the contemporary Special Drama Community. He is revered and honoured by special drama artists as a guru and as the founder and first teacher of their art form.

According to Nasser, a veteran actor in south Indian film industry, Swamigal’s picture is placed along with other God’s images and idols in the houses of many theatre artists.

“The decades in which Swamigal wrote these plays was a time of intense intellectual foment and radical idealism across the south. The excitement generated during this period carried over to the reformist ideals that continue to shape artists’ political goals today,” added Seizer.

The special drama genre and the development of Boys Companies, where only male children were given training in theatre, grew hand in hand.

In 1910, Swamigal started his own drama company named Samarasa Sanmarkka Sabha. It was in this company that yesteryear superstar SG Kittappa and his brothers underwent training.

In 1918, Swamigal along with his friends such as Palaniya Pillai, founded ‘Tattuva Meenalochani Vidwat Balasabha’, another Boys Company. Till his death in 1922, Swamigal remained associated with this company.

The reason why he chose to work with Boys Companies, after starting his own company for adult actors, was because of the latter’s insubordination.

“On seeing that adult actors whom he had trained were not following his lessons, he was heartbroken. So, he formed a company of the best young male actors and began running that instead,” writes Ulaganathan, one of the biographers of Swamigal.

Tamil theatre in today’s milieu

On Sankaradas Swamigal’s death centenary, it is pertinent to take stock of how Tamil theatre is faring. Parthibaraja, who also works as a Tamil professor in Sacred Heart College, Tirupattur, says Tamil theatre is working against the tide of film industry.

“In southern Tamil Nadu, the different genres of dramas like the special dramas, musical dramas and Therukkoothu [street play] are still performed with rigour. Places like Pudukkottai, Karaikkudi, Dindigul, Manapparai, Karur and Ponnamaravathi have drama artist associations that are carrying forward the legacy of Swamigal.

“In Madurai, drama artists association alone had booked about 60 drama performances during Chithra Pournami (a festival celebrated in the Tamil month of Chithirai in April or May). Similarly, the number of artists is also increasing in the state,” he said.

In states like Karnataka, Maharashtra and West Bengal, people give equal importance to theatre and films. Even schools teach performing arts. “Such efforts are the need of the hour in Tamil Nadu,” added Parthibaraja.

Veli Rangarajan, a theatre artist and writer, said that in Tamil, theatre has moved from a point where people came to watch dramas, to theatre being taken to the people.

“Today, dramas are staged in various formats such as modern theatre, mime, street play and ‘nija natakam’ (a real drama) among others. The transition is akin to what happened in Tamil poetry. The poets moved from using meters to writing free verses. Though films dominate, theatre is still alive because it is closer to people. You can feel and touch. You can went out your frustration and anger. You can get the responses for your play then and there. While films distance people from the story, theatre makes the audience a part of the story,” he added.