- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

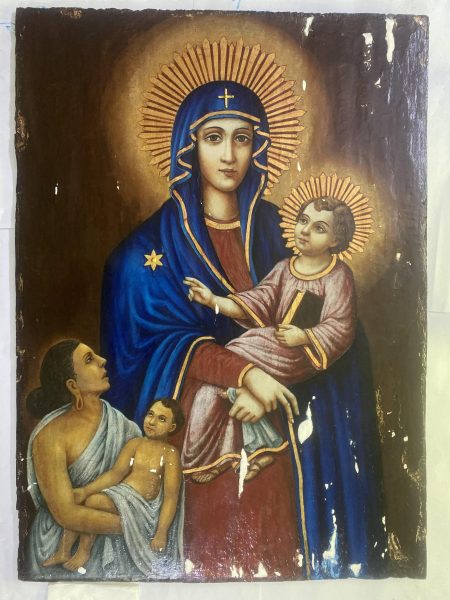

How restoration of a 500-yr-old painting revealed hidden strokes of genius

When 28-year-old Sathyajith Ibn set out to restore a 500-year-old painting, little did he expect to see the true shades of genius hidden behind years of grime and coats of varnish and overpainting from ‘botched’ restoration attempts in the past. The popular painting of Our Lady of Ransom – believed to have been shipped to India from Portugal close to 500 years ago and mounted on the...

When 28-year-old Sathyajith Ibn set out to restore a 500-year-old painting, little did he expect to see the true shades of genius hidden behind years of grime and coats of varnish and overpainting from ‘botched’ restoration attempts in the past.

The popular painting of Our Lady of Ransom – believed to have been shipped to India from Portugal close to 500 years ago and mounted on the altar of the Vallarpadam Basilica – has a host of myths and legends associated with it. And when Sathyajith, a native of Pathanapuram in Kollam district of Kerala, laid his hands on the painting, it was certainly crying for help.

For Sathyajith, who has a masters degree in design from the National Museum in New Delhi, restoring paintings, antiques and designing museums is a passion. He has recently completed designing the Kerala Museum at Sree Sankaracharya University.

Currently undertaking research on traditional materials and sustainable methods to conserve artefacts and architecture of historical value, Satyajith designed the museum to promote perspectives on sustainable patterns adopted by indigenous people.

His latest project involves using sustainable means to restore the painting of Our Lady of Ransom.

Who is Our Lady of Ransom

Mary, the Mother of Jesus is known through many different titles mythologically based on how she is believed to have appeared to help those in need. In each of those cases, the church gives her a special title that emphasises the help extended. Our Lady of Ransom is one of those titles for Mary.

In 1218 AD, Mary is said to have appeared in separate visions before St. Peter Nolasco, St. Raymond of Penafort, and King James I of Aragon asking them to liberate Christians who had been kidnapped by the Moors, transported to African prisons, and forced with torture to deny their faith in Christ. Mary asked the men in whose vision she appeared to establish a new order, Order of Mercedarians, whose members were to do this through prayer, raising money to pay for ransom, and taking a vow to offer themselves, if needed, in exchange for the enslaved Christians.

It is said tens of thousands were freed by paying a ransom earning Mary a new title – Our Lady of Ransom. It is for this reason that paintings of Our Lady of Ransom always show her protecting people with her mantle or robe.

Many of these paintings travelled across the world. One such painting was brought to Kerala in the 16th Century CE by the Portuguese and Spaniards. The painting that Sathyajith Ibn has restored, however, isn’t the same.

It is popularly believed that the painting brought in by Portuguese and Spaniards missionaries depicted only Our Lady of Ransom and infant Jesus. But in 1752 the images of a local woman named Vallarpadam native Meenakshiamma, a Nair, and her son, again an infant, were added to it.

Legend has it that while the mother was out with her son on a boat to her family temple at Mattancherry, their boat met with an accident. They faced the vagaries of the sea until they were miraculously rescued three days later. Following the incident, Meenakshiamma and her son became ardent worshippers of Mother Mary. After the demise of Meenakshiamma the then parish priest of the Church undertook an initiative to get the picture of the mother-son duo on the original painting to portray their devotion to Virgin Mary.

The legend of Meenakshiamma is popular among the locals of Vallarpadam.

“Though there is no exact assessment of the period in which the picture was drawn, it may be after the demise of Meenakshiamma. The descendants of Meenakshiamma still perform some rituals at the church during the church festival. Recently, Meenakshiamma’s family donated their old house to the church,” Vicar of the National Shrine Basilica of Our Lady of Ransom, Vallarpadam, Father Antony Valunkal told The Federal.

The restoration

The oil painting, believed to be 500 years old, was damaged due to warping issues. It also faced paint loss, overpainting and colour alterations among a host of other issues.

“The conservation project first ensured the current deterioration process came to a halt and revived the original paint layer hidden underneath layers of varnish and overpaint. The conservation work was undertaken with the help of scientific and conservation grade materials, through which the material science embedded within the painting was addressed and the identity revived and retained,” said Sathyajith Ibn.

Since the painting has been housed in a place with high relative humidity, it suffered damages due to the anisotropic nature of wood used for the back support. The humidity led to uneven contractions and expansions which in turn damaged the layers of paint.

It took over 10 days to just remove the years of grime and varnish. The last restoration of the painting was done about 18 years ago. The current work was carried out in connection with the 500th anniversary of the installation of the painting on the main altar of the church.

The work commenced with photographic and graphic documentation followed by raking light imaging to understand the surface contour of the paint layer. Even though the paint layer looks 2-dimensional, the minute details in surface morphology were difficult to see under direct light.

Methods of photography using raking light helped in critically understanding the paint surface and observing areas of damages and issues that needed to be addressed. Conservation steps included stabilising of the wooden panel followed by the cleaning of superficial damages and the varnish layer.

“Conservation grade solvents were used for cleaning which helped retain the original work and aided in removing the recent additions and depositions. The cleaning process helped revive the original colours present within the painting,” Sathyajith told The Federal.

This was followed by consolidating the paint layer with conservation grade materials after which inert fillers were used to plug the gaps from which paint had disappeared. The consolidation process ensured reattaching the detached paint layers by reactivating the historic binders within the paint layer along with addition of heat activated new adhesives where major detachments were evident. An isolation layer was applied prior to the retouching process in order to ensure that the newly added conservation grade materials do not chemically react with the original authentic paint layer. Natural pigments were mixed with conservation grade binders in order to undertake the retouching process. A significant factor that was considered here was the possibility of retreatability of the painting which was ensured by the materials that were precisely used for the work.

Sathyajith’s previous restoration works include the conservation of the historic plasters of the St Peter’s and Paul’s Church where scientific tests of XRD and C 14 dating were undertaken on the plaster samples and the pottery sherds from the site underneath the foundations.

The conservation of the historic church was done post scientific analysis where mortars and plaster were made using the historic process using traditional materials. The work was an attempt to pause the deterioration process, so that the historicity of the church is delved into and the past of the sacredness is understood and exhibited.

The efforts were aimed at facilitating an in situ museum that includes the exhibition of the site as it is, by creating glass pathways above the identified features, above which the church will perform its daily chores. The church space is currently open to visitors to understand the architectural past of the sacred space which is exhibited beneath the present.