- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How news photography keeps us connected to a past we did not see

In the 2022 Booker Prize winning book, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida (earlier published as Chats with the Dead), by well-known Sri Lankan writer Shehan Karunatilaka, the news photographer is the (dead) hero. Maali’s story, though fictional, finds an eerie similarity in the works of countless news photographers in India. Unfortunately, history’s visual documenters themselves have...

In the 2022 Booker Prize winning book, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida (earlier published as Chats with the Dead), by well-known Sri Lankan writer Shehan Karunatilaka, the news photographer is the (dead) hero. Maali’s story, though fictional, finds an eerie similarity in the works of countless news photographers in India. Unfortunately, history’s visual documenters themselves have rarely been documented and their stories told, like Shehan had done in his surrealistic novel.

Maali was there to photograph every bloody incident that took place during Sri Lanka’s tumultuous Civil War years — 1983 to 2009 — and the rise and fall of LTTE, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna and other small and big terror groups before he was himself killed brutally. Maali is what every photo journalist wants to be. Only a few come close.

“You were born before Elvis had his first hit. And died before Freddie had his last. In the interim you had shot thousands. You have photographs of 1983’s savages, pics of Vijaya’s killer and shots of Wijeweera being kicked in the head. You have the wreckage of Upali’s plane on film and a Kodachrome snap of The Supremo’s lover fleeing Mullaituvu. You have these images in a white shoe box hidden with old records by Elvis and Freddie, the King and Queen. Under a bed that your Mama’s cook shares with your Dada’s driver. If you could, you would make a thousand copies of each photo and paste them all over Colombo. Surely, you still can.”

Many photographs, thousands of them, taken by our news photographers are pasted on history’s battered wailing walls.

We walk past them every day of our lives, wanting to continue remembering some, forgetting others.

But how have India’s news photographers helped us in understanding the past be it glory or gore? The author tries to piece together how these photographs help us understand our last 50 years and how much are these pictures embedded in the country’s collective conscience.

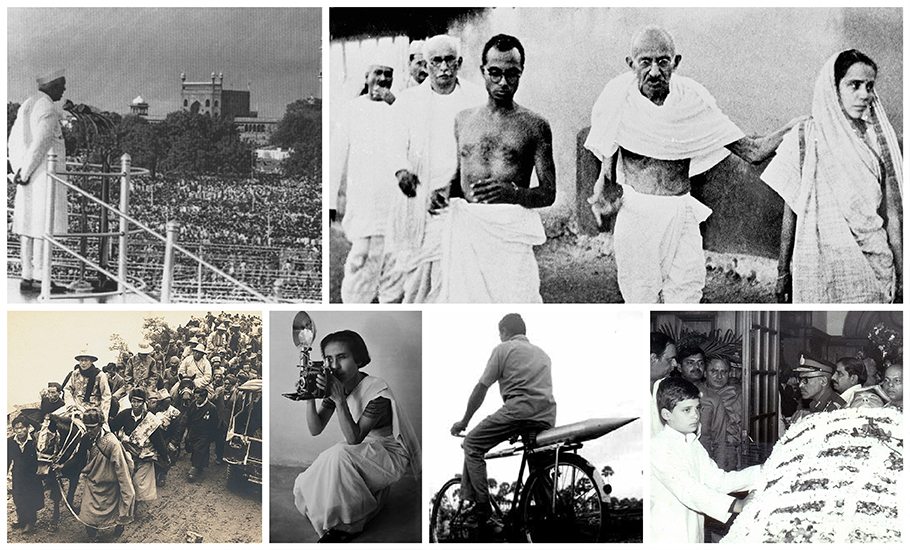

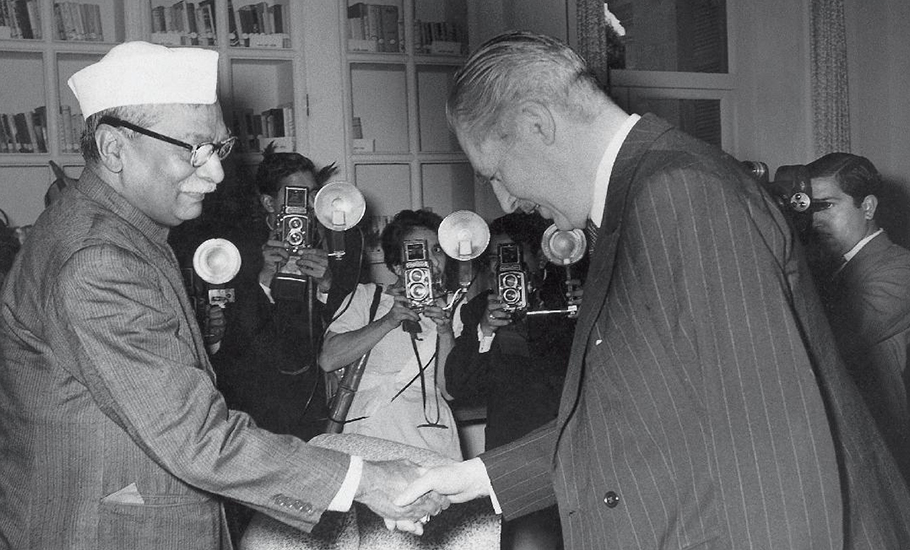

Dignitaries being received by the President of India make a common subject for news photographers in Delhi. In such a picture taken in 1954, then President Rajendra Prasad is seen welcoming British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. In this picture, we can see positioned right in the middle between the offered hands of Prasad and Macmillan, Homai Vyarawalla perfectly and just about to capture the moment with her twin lens reflex Rolleiflex attached to a weighty flashbulb. Like the other three photographers all holding the same Rolleiflex, Homai too held the unwieldy flash stand with her left hand betraying the calm composure of a veteran who knows when to click, what the moment is all about and seemingly cold about the gravitas of the occasion.

Homai is critical to the rise of news photography in India, with her role as a photo journalist running parallel to the rise of a new nation emerging after shaking away the yoke of colonial rule and also trying to come to terms with Partition. The sari-clad Homai had a ring-side view of the nation taking shape. She was everywhere and it was as if nothing happened if she wasn’t there. Homai never realised she was creating history of her own even as she made a regular presence by the side of Jawaharlal Nehru, Mahatma Gandhi and MA Jinnah.

It is photographers like Homai who laid the foundation for the later crop of photographers to chronicle an India that was changing fast. News photographers of the post-Emergency period too had access to the inner ring of powerful people, at least until the assassination of Indira Gandhi and later Rajiv Gandhi. But unlike Homai and Kulwant Roy and a few others, the photographers of the new age had other concerns such as natural disasters, terrorism and violent skirmishes around the country.

Access, of course, was important and many photographers were always found themselves close to action. In one classic picture by Raghu Rai, Indira Gandhi is shown surrounded by a semi-circle of fawning ministers most with Gandhi caps. It showed her in all her imperial might. Rai said he entered the room through a back door and saw this stunning scene and did not waste even seconds before clicking the classic. Raghu Rai was the shining star of the period under study and led an army of superb photographers who changed news photography forever.

Access was important and all Prime Ministers secretly liked to be photographed. Rohit Chawla, a fashion photographer and portraitist recently uploaded on Facebook a picture of him getting ready to shoot Atal Bihari Vajpayee on the lawns of the PM’s residence with an amused PM standing like a kid awaiting instructions as Chawla, with Nikon and zoom lenses dangling on his shoulder, was doing just that: issuing instructions.

This classic picture obviously shot by an assistant, was endearing and powerful in many ways. It was a shoot for a BJP poster and such was the power of medium those days that PMs happily went along, more so a jovial Vajpayee who loved chatting up journalists and started the practice of visiting the Women’s Press Club in Delhi annually, in what turned out to be fantastic photo-op that captured the power of the press and its closeness to power and democracy at work.

Here the photographer was “a fair-minded witness free of chauvinistic prejudices” as the first Magnum agency charter proclaimed. Such pictures also created “an illusion of consensus” as Susan Sontag wrote in a different context about war pictures.

News photography from 1975 was full of action, drama and tragedy. It captured the struggles of a new nation trying to shirk off the vestiges of the old. It wasn’t so just because Emergency was declared in 1975, but also because it was a landmark decade for journalism. Two English news magazines India Today and Sunday had captured the attention of the nation by the late 1970s. These magazines changed news photography. We looked amused and bewildered at the killings and bombings our country went through and these magazines gave us a ring-side view both in terms of reporting and photographs.

Many news photographers were there as one tragedy after another washed over the country’s shores.

The two magazines over the next two decades or so dominated journalism not just through the path-breaking reports they carried but also through their photographs taken by an array of top photographers who grew into their jobs. I worked in both magazines during the two decades from 1980 onwards and thus knew all the photographers and sometimes went for shoots with them, for the news features I did, even though I worked largely on the news desk and also edited and produced the magazines.

Homai, along with others like Kulwant Roy (an exhibition of Roy’s pictures is on at Museo Camera in Gurgaon October-November), were pioneers of Indian news photography post-Independence. They had done a phenomenal job and so those who came after had a tough job matching up.

But by the 1980s, India had changed with its Prime Minister Indira Gandhi making a comeback to power and then being assassinated, the rise in anti-Sikh violence, the emergence of the BJP from the embers of Jana Sangh, and rising communal tensions.

Reportage and photography too changed with the times. Apart from a slew of top reporters, mostly in India Today and Sunday, photographers also contributed to the change in telling stories. The Emergency itself, the death of (Sanjay Gandhi, the assassination of Indira Gandhi, the 1983 World Cup win, the Nellie massacre, Bhopal gas tragedy, Operation Bluestar passed before our eyes through still photographs. The 1990s was even worse with the killing of Rajiv Gandhi and the dangerous form taken by LTTE as a terror group.

***

Post 1975, news photography changed with many technological advancements kicking in. New SLR cameras and zoom lenses were becoming available in India. Films were getting more sensitive to light. 400 ASA films were being regularly used to avoid using flashbulbs which often overexposed the face of the subject, cut the depth of field and altogether made the picture look too static with no drama or movement. Later, 800 ASA films too became a favourite of Indian news photographers saving them the trouble of carrying flashbulbs, which had by then become a tiny appendage which could be slipped into the top of the camera, unlike the heavy hand-held ones which Roy and Homai had to lug around New Delhi. Many photographers looked down upon those who used flash. But the flash was always in the camera box of the news photographers because you never knew how well lit the room in which a function was about to take place would be.

It is around the 1980s that beauty and art, irony and humour came into news photography led by Raghu, his brother S Paul, Raghubir Singh, Sondeep Shankar, and many others named later in this article. The Statesman published a picture of Rai which showed a sweeper in Calcutta (now Kolkata) sweeping posters put up by parties in the 1977 general election. The lot included a poster of Indira Gandhi. The photo was seen as a symbolic of Indira Gandhi’s impending electoral loss.

All these photographs taken with quick thinking could not have happened without the light cameras, lenses which could be screwed on 200 mm lenses which helped outfocus the background by increasing the aperture while focussing just on the face. And also, of course, the motor drive which could be fixed to the bottom of the camera and could take 3 frames per second. In contrast, today one can take more than 10 photos per second and can capture even the blur of an athlete finishing the 100 metre race. Even a separate motor wind was not required. So lot of photographs in the 1980s, 1990s and later looked much different than they would earlier on.

Technology was changing and more so the camera could easily be slung on the shoulder.

The likes of Raghu Bhawan Singh and Pramod Pushkarna could often be seen walking like that. A news photographer was always ready, his armour all set for shooting.

Proximity and destiny

A news photographer’s life and work, unlike that of a portraitist or fashion photographer depends on his timing or luck. They need to be at the right place at the right time for a historical picture. Homai was all set to go to Gandhi’s fast on January 30, 1948, and had stepped out of the office in Connaught Place with a colour movie camera when her husband Manekshaw Jamshetji came and told her they would go the next day and he would accompany her with another camera. And so she missed the biggest event in India’s history. She rushed there soon after but that for a photographer, unlike that for a reporter, meant the big picture had been missed. A reporter could stitch up the story but the photographer’s moment was gone for ever.

Many years later, in 1993, I was riding my Fiat car along Raisina Road leading up to Parliament. My destination was the Press Club where my plan was a beer-soaked lunch. About 50 metres from the club was the Youth Congress office (still is) where a huge crowd was present, to receive party president Maninderjeet Singh Bitta. I slowed down for a while to figure out the scene and then moved on to the club. As soon as I sat down in the verandah, I heard what could only have been a bomb blast. I rushed out to see fire and chaos all round.

Among those present at the club was Pioneer photographer Praveen Jain who was by then making a name for himself by shooting impish political photographs. The next day Pioneer had Jain’s classic picture. A policeman carrying the severed head of a man by the hair and crossing Raisina, just 10 minutes after the blast. The severed head told one story and the policeman, who carried the head like it was a shopping bag, told another. The debris around captured the totality of the disaster. It was a picture that foretold a period of terrorism and tumult in India.

It was Praveen’s destiny that he was there.

Again some years later, Praveen was there in Hashimpura near Meerut when the police rounded up some Muslims from a riot scene and took them in a van to a nearby place. Praveen followed. When they were taken out in a single line, Jain captured the image. Soon after, the UP police shot dead all of them in a classic case of “encounter deaths” which the police all over India had mastered as an art of ‘instant justice’. Praveen’s photo became clinging evidence as 20 years later all the cops involved in the ‘encounter deaths’ were convicted.

Raghu was once walking along Raj Path, now Kartavya Path, near India Gate, when he saw Rajiv Gandhi and Sonia having ice cream from a streetside vendor. The couple were a bit aghast but the picture was a classic in many ways. To be always wandering the streets in search of such a picture is the news photographer’s raison d’etre.

Can classic photograph be a thing of beauty?

News photography is often seen as very different from landscape photography where all beauty can be captured. A news photo is a reflection of reality, which can be good, bad or ugly. Wars, natural disasters and terrorism have been covered by Indian cameramen with courage and utter disregard for their own lives. During the heights of terrorism in Punjab demanding Khalistan, Pramod Pushkarna, my colleague in India Today, was walking down a street in Ludhiana when a bomb went off. Unfazed Pramod turned his camera towards the scene of death and destruction that unfolded right in front of his eyes. The picture had an eerie beauty to it with small flames lighting up the frame here and there as if those were lights kept there by Pramod himself to outwit the enveloping darkness. The dead and the debris were all over.

Pramod was always unfazed and was became a stalwart in news photography, especially during the 1990s. He approached a scene like a conqueror, his camera serving as an entry pass everywhere. Even when policemen surrounded scenes of disaster, where a VIP was scheduled to land to take stock, he would manage to position himself where he wanted to be, sometimes even by pushing the police personnel or entering into a verbal duel with them.

Security personnel tend to always form the first barrier for journalists and photographers reaching the site of a disaster or triumph. Preventing the chronicling of truth, stopping people from seeing and assessing the truth about the scale of destruction and death is their primary duty. In doing so, they invariably place themselves at the other end of the spectrum from reporters and photographers who are in many ways present the first drafts of history.

Time and again, news reports and photographs have belied the ‘official version’ of the truth. For photographers and reporters, dealing with security officials has always been a muscular pursuit, which all news photographers have had to master out of necessity. But none aced it like Pramod. For him the image, the moment mattered so much that he would do anything to get there. No one could stand in his way. Many news men like him have seen blood spilled on their shirts and their lenses smashed while trying to get the perfect shot.

In their hunt for the right click, photo journalists have seen many sites of disasters turn into sources of eerie tragic beauty. One such instance was when Rai captured the close up of a kid’s face disfigured by the leaking gas in Bhopal, which came to signify the horror of the tragedy. Rai’s photo makes it look like the child had been put to sleep peacefully.

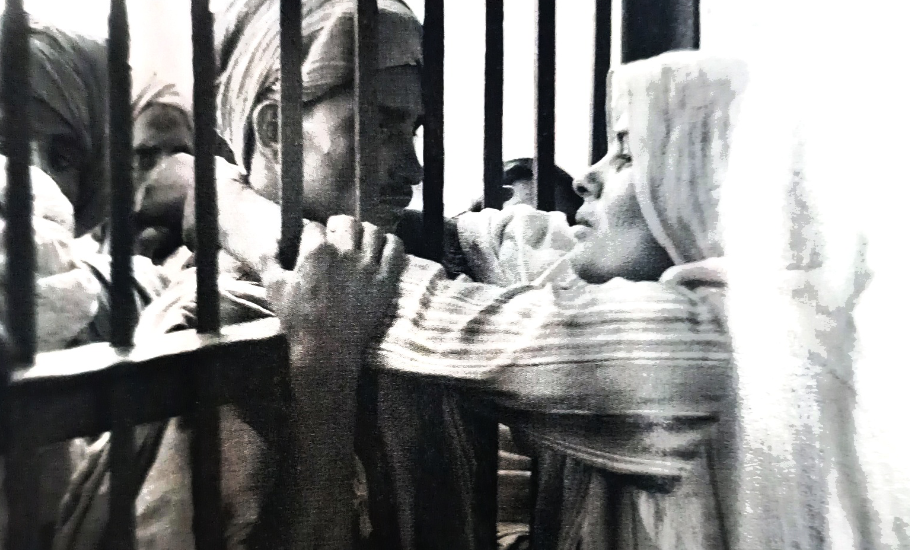

Such eerie beauty hasn’t just been captured by Indian photographers but even those from overseas trying to chronicle India through their lenses. Many European photographers came regularly to chronicle India during the early part of the 20th century. Cartier Bresson’s 1948 pic ‘Muslim women praying at dawn in Srinagar’ has an uncanny beauty to it.

His 1966 click from the rocket launching station in Trivandrum of the rocket nose being carried on a bicycle is used even today to remind us that so much has unchanged about the country. Bresson had all the luck that a photographer could ask for in his pictures, which have become timeless.

He was a specialist of ‘moment photography’ and his picture of Nehru laughing like a teenaged boy by the side of Lady Mountbatten sparked stories of their romantic attachment.

These photos continue to keep us connected to a past we did not see or have only a fleeting memory of. More often than not when we marvel at the photographs, we are oblivious to the photographers and their effort in capturing and preserving history for us.