- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How Koyambedu market became a COVID-19 super-spreader

Panic gripped Inbaraj when the police took scores of daily wage labourers engaged in loading and unloading vegetables and fruits from Chennai’s Koyambedu market for COVID-19 testing in early May. Since the lockdown was imposed on March 24, the scene at Asia’s largest perishable goods market had been scary. He has been striving hard for a meal. “Even drinking water suppliers avoided...

Panic gripped Inbaraj when the police took scores of daily wage labourers engaged in loading and unloading vegetables and fruits from Chennai’s Koyambedu market for COVID-19 testing in early May.

Since the lockdown was imposed on March 24, the scene at Asia’s largest perishable goods market had been scary. He has been striving hard for a meal. “Even drinking water suppliers avoided coming to Koyambedu fearing that they might contract the disease, leaving us high and dry,” he says.

In mid-April, Inbaraj and his co-workers ordered food from a restaurant run by their owner’s brother. But they never repeated it as each meal cost ₹100.

Despite knowing that he would soon go broke if he returned to his native village in Perambalur district, about 260 km away, he set out on the arduous journey on foot, and after facing humiliation several times for turning his back on the city that gave him livelihood, he reached home two days later.

Thousands of workers like Inbaraj had rushed to their villages after the incident, which VR Soundararajan, president of the potato traders’ association, claims was done without consulting the traders.

A 30-year-old vegetable retailer, who has been selling brinjal and ladies’ fingers at the market for 12 years, may have been the first reported COVID-19 case from the market. He shut his shop as soon as the retail trade was banned in Koyambedu on April 28 and returned to his native village in Cuddalore district. On May 1, he tested positive for COVID-19.

This happened soon after the Tamil Nadu government announced a lockdown within a lockdown on April 26 for four days. Lakhs of people had thronged the Koyambedu market flouting all physical distancing norms. No police or health personnel were seen regulating the crowd.

This proved costly as around 2,600 people have contracted the disease from the market so far.

Besides, with the shutting of thousands of shops, some of which were shifted to two different locations, the lives of over 20,000 families of workers, sellers, traders and accountants are in dire straits.

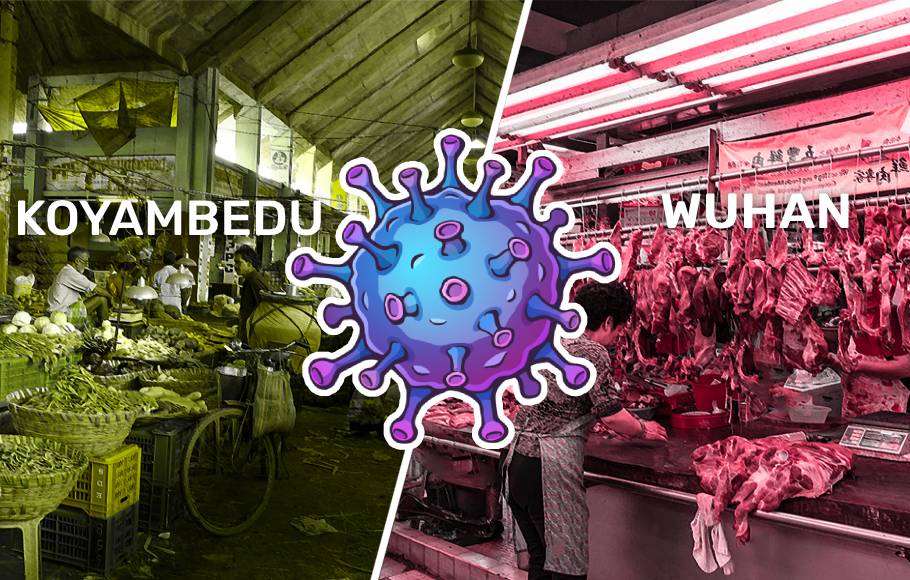

Another Wuhan?

People were quick to compare it to the Wuhan wet market in China, which is said to be the ground zero of SARS-CoV-2.

According to Chinese authorities, Wuhan market, where sea animals and wild animals were sold, was the likely source of many early cases of coronavirus, which forced its shutting on January 1, 2020. It was opened on April 17, after no new cases were reported for more than a month.

Experts believe that viruses can spread and mutate from one animal to another or to humans when kept in dirty, cramped conditions, putting them under duress, especially sick animals.

A senior official of Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) J Radhakrishnan, however, pointed out that while the Huanan Wholesale Seafood Market in Wuhan was said to be the place where coronavirus transferred from bats to humans, in Koyambedu, the virus may have been transmitted by some person. “Coronavirus did not originate in Koyambedu. Please don’t compare the two markets,” he was quoted as saying by Times of India.

But apart from that, both the markets see overcrowding, poor disposal of garbage and sanitation. And both are sources of affordable food and livelihood to thousands.

Blame game

Soon after the positive cases were reported in Koyambedu, the government quickly pointed fingers at the market for the spike in the capital city and across the state, much like the Centre blamed the Tablighi Jamaat event for COVID spread across the country in April.

Soundararajan says the government never disinfected the whole market complex.

K Kolandaswamy, who was the public health director when the Koyambedu cluster emerged, says the government did whatever it could to slow down the spread of the virus.

“We did thermal screening at all entry points, installed handwashing facilities and provided people with masks, and sanitized the market. But the virus is very infectious in nature. So there is no way of stopping it from spreading, but only to slow down the process,” he says.

And even now, only around 200 vegetable shops have been shifted to Thirumazhisai and 200 fruit shops to Madhavaram. Families of the remaining 3,000-plus sellers have been left in the lurch, says M Thyagarajan, president of the Koyambedu Fruits, Vegetables and Flower Merchants’ Association.

A goof-up retailed

Soundararajan says the spread of the virus was due to the retail shops in the market. “We did manage to maintain physical distancing at the wholesale block. But it was hardly possible at the retail block.”

Unlike other wholesale markets like Azadpur Mandi in Delhi, where the trade is only wholesale, Koyambedu market has around 2,000 retail shops too.

In 1996, the Koyambedu market was inaugurated on the outskirts of Chennai to decongest the other big market in the city, Kothawal Chavadi situated adjacent to George Town.

“Workers, traders and customers would walk ankle-deep in sludge in Kothawal Chavadi. After petitioning the government several times to set up another market, it finally heeded our demand in 1982,” says Soundararajan, who has been a trader for the last 50 years.

Many traders like Soundararajan paid 40 instalments to own a shop at the wholesale market. But their relief was short-lived. “Initially, the market was very spacious. The retail market was to be set up in the area where the omnibus stand is currently located. But the CMDA (Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority) allotted the land to omnibus operators. This resulted in the retail shops popping up in the market complex,” he says.

Thyagarajan says the main reason for the spread of the virus on the market premises were unlicensed traders, who encroached upon the market area and pavement, and the licensed ones, who advanced beyond their limits. Generally, retailers extend their shop limits by placing slabs, on which vegetables, fruits and flowers are kept for sale. So the already narrow passage turns congested and unpleasant, he says.

Garbage land

For anybody visiting the vast market, which gets all kinds of vegetables, fruits and flowers from across the country, it is only normal to walk over mashed brinjals, cabbages, tomatoes and vegetable leaves strewn rotting on the narrow lanes of the retail market. The sight and smell is nauseating. Waste management has always made headlines for the wrong reasons.

The Koyambedu market churns out about 150 tonnes of garbage every day and the stench from the rotting vegetable waste is almost proof for the waste management failure in the market.

“The dumping site behind the market is inaccessible to a lot of shops due to which sellers throw the waste right outside their shops making the pathway filthy,” says ecologist Sultan Ahmed Ismail.

“To combat this, a bio-gas plant was installed in 2006 by the corporation and the contract was given to a private agency,” says Ismail.

However, in 2018, the bio-methanation plant was rendered inoperable after machinery reported problems frequently. Sultan says the biogas plant was big and the garbage did not have enough calorific value to generate biofuel consistently.

‘Approach before reproach’

As retailers buy vegetables and fruits from the wholesale block, Soundararajan suspects it could have spread to workers too. Besides thousands of workers like Inbaraj who unload vegetables from trucks, there are also many outsiders who are employed in loading goods onto lorries that transport vegetables to shops across the city and from other parts of the state.

“At least, we had been given a space inside our shops to sleep. But what about thousands of outsiders who catch a wink by the roadside?” asks Inbaraj.

There is no point talking about physical distancing if workers are not provided with bathrooms and separate rooms to sleep, says MB Nirmal, founder of Exnora International, a Chennai-based NGO for environment protection which has been given the contract to maintain cleanliness in the market for three years. “If 2,000 daily wage labourers sleep inside shops and on market premises, how can the virus not spread?” he asks.

Solution for the dense city

Since cities are about densities and agglomeration, the government should have anticipated the crisis and managed it, instead of shutting the market down, says Karen Coelho, associate professor at the Madras Institute of Development Studies (MIDS).

“Decentralising the hub should have been thought of well in advance as a matter of urban spatial and economic planning. It has been 25 years since the construction of the market and it is pertinent now to revisit these models,” she says.

Coelho says the need of the hour is to establish two or three wholesale markets in each suburb, depending on where the produce is coming from.

Advocating a more traditional form of decentralising markets, Ismail suggests bringing back the ‘Uzhavar Sandhai’ or farmer’s market model in each zone. Farmers can directly bring their produce to the markets, spend less on transporting the produce and the people will also be happy to access it in their locality at nominal rates, instead of flocking to a single large market, he says.

“In markets like Koyambedu, shops can be segregated into odd and even numbers, and permitted to function only on alternative days to reduce congestion. All 15 zones in the city can also be categorised as odd and even and allowed only during their turn. At the end of the week, the market needs to be shut completely and sanitised. Only if this is enforced strictly, the congestion can be reduced,” suggests Ismail.

Not only the market, but also many other structures need to be decongested, says Kolandaswamy. “We have to follow Abdul Kalam’s PURA (Provision of Urban Amenities in Rural Areas) formula to prevent huge migration to cities and decongest hospitals, markets, malls and so on.”

“The only time I saw the market clean was the inaugural day,” laughs Nirmal of Exnora. The market witnesses complete lawlessness, haphazard parking of vehicles and almost 2,000 daily wagers sleeping on its premises, he says, stressing that the Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority (CMDA) needs to have a clear plan.

Sadly, Koyambedu is back to where Kothawal Chavadi was 25 years ago.