- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How IPL helped football, kabaddi get rich but not grow roots

The IPL model, when applied to other sports, will definitely find some success, but it cannot be considered a solution in the long run.

April 18, 2008. There was palpable excitement at the Chinnaswamy Stadium in Bengaluru. Shankar-Ehsaan-Loy were playing at the opening ceremony of a new cricketing league, preceding a match that would see teams owned by (hitherto) popular business scion Vijay Mallya and Bollywood’s biggest superstar Shah Rukh Khan square off against each other. Something big was about to happen, something...

April 18, 2008. There was palpable excitement at the Chinnaswamy Stadium in Bengaluru. Shankar-Ehsaan-Loy were playing at the opening ceremony of a new cricketing league, preceding a match that would see teams owned by (hitherto) popular business scion Vijay Mallya and Bollywood’s biggest superstar Shah Rukh Khan square off against each other. Something big was about to happen, something that would change the face of Indian cricket.

As Brendon McCullum powered his way to an astonishing 158, you could sense the Indian Premier League (IPL) was here to stay. And stay it did, changing not only the face of Indian cricket, but Indian sport as a whole.

Eleven years on, you do not need to go through the numbers to judge if the IPL was a success. If you do, here is what you come across: a title sponsorship deal worth ₹2,200 crore for five years, a five-year broadcasting deal worth over ₹16,000 crore, viewership of 462 million and an estimated brand value of $6.3 billion. The secret of the IPL’s success lay in how it combined a heady mix of sport and entertainment, arriving at a concoction that even the casual fans could tune into and enjoy.

Replicated to other sports

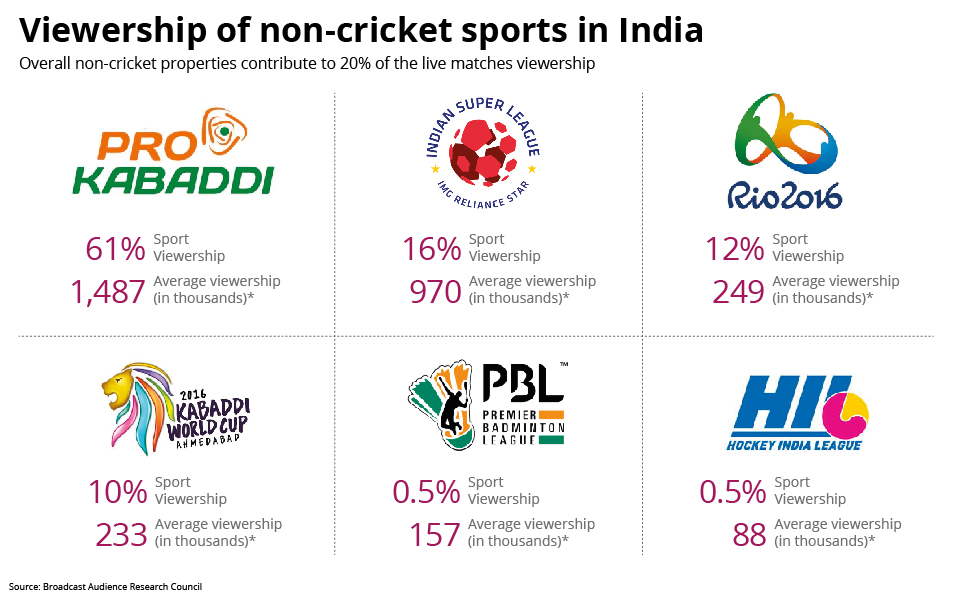

The runaway success of the IPL got brains whirring in the sporting and business fraternities of the country — could this league model be replicated in other sports as well? The challenge, of course, was that the IPL dabbled in cricket, a sport that commands 93 per cent of sports viewership on television in India. However, it was argued that the IPL managed to attract people not interested in cricket or even sports due to the entertainment and star power it showcased, surely that should be sufficient for other sporting leagues to be successful, albeit on a much smaller scale. And in the process, generate awareness and interest about the sport and gradually turn India into a breeding ground for world-class talent.

The Indian Super League (ISL) was the first to accept the challenge in 2013, with Reliance and Nita Ambani at the forefront of the football league. The ISL had star power in plenty, with team owners ranging from cricketing superstars Sachin Tendulkar, Sourav Ganguly and Virat Kohli to Bollywood A-listers Ranbir Kapoor and Abhishek Bachchan. And it came with a promise of showcasing footballing greats who had plied their trade in the topmost tier during their heyday. The league started amid controversy with the existing I-League, with neither side willing to cede ground to a peaceful coexistence.

But, just like the IPL, the ISL began with a roar, gathering an average stadium attendance of 24,357 during its first season, making it the world’s fourth most attended football league after the English Premier League, La Liga and Bundesliga — an astonishing feat for a country ranked 101st in the world. Five seasons later, the ISL is going pretty strong, with an average viewership of 2.2 million per match last year. The I-League (0.37 million viewership per month) has been blown out of the water. That it has impacted even casual fans is apparent — the ISL is viewed in India a whopping 20 times more than the English Premier League!

Another league that became really successful with the IPL model was the Pro-Kabaddi League (PKL). It completely changed the kabaddi experience to a casual viewer, making it an entertaining watch. The PKL surpassed the ISL with ease and become the most-watched non-cricket league in the country. PKL 5, the most successful edition, had a viewership of 313 million. The final drew a staggering 26.2 million impressions that put it in comparison with the IPL final of the same year that clocked in at 39.4 million.

A key component in the PKL’s success was rural viewership, which comprised 47 per cent of its viewership. Similarly, the Pro-Wrestling League saw a viewership of 33 million this year, with almost 50 per cent of it from rural areas. Taking a sport that every person in rural India knows, and converting it into a franchise-based league was a gamble that paid off very well for the organisers.

Recently, the Pro-Badminton League has encountered similar success. After a slow start in its initial years, the badminton league saw ratings soar by 270 per cent last year, attributed to the decision to have vernacular broadcast for the matches, as well as India’s dominance in world badminton, riding on the backs of the Sindhus, Nehwals and Srikanths. Recently, the Pro-Volleyball League got an encouraging start, gaining 14.3 million viewers in its inaugural week.

All is not well

However, not all is as rosy as it looks. While there have been some massive and moderate successes, not all leagues have been so lucky. After the success of the IPL, leagues have sprung up in every imaginable sport — from table tennis to MMA. And a lot of them have sunk, some gradually, but most quickly and without a trace. Some leagues to disappear in the past year include the Super Boxing League and the UBA Pro-Basketball Alliance.

Usually it’s a lack of big names or crowd connect to the sport that cause the decline of these leagues. With a lack of crowd connect, the organisers and owners need to pump in capital to get the league to the audience, which becomes infeasible in the long run.

Some failures, though, are highly surprising. Take the case of the Hockey India League. The league started in 2013 with moderate success, gaining 41.3 million views. With plenty of international talent and the organisers splashing money, there was hope that the league would revive the country’s interest in hockey. However, five years later, the league has not managed to get much traction, and in 2018, it was announced that no league would take place that year. Though an overburdened schedule for the players was pointed out as reason, one is tempted to believe that lack of sponsors, owners bleeding money, and next to no viewership interest had parts to play in the decision. There is a 2019 edition scheduled late in the year, but that also looks tepid.

Even for established leagues, viewer fatigue is a substantial issue leading to declining numbers, as are improper scheduling and lack of glamour. Both the PKL and ISL have borne the brunt of this. The PKL’s schedule shift to October 2018 saw ratings drop by 26 per cent last year, as it had to compete with the India-Australia series, as well as the generally busy Diwali season. The ISL, meanwhile, has also seen a decline in viewership, with a lot of fingers being pointed at most international stars being injury-prone and well past their prime. While the ISL has splashed some money, it is still incomparable to the fees thrown at footballers in Europe or even in the USA, China or West Asia where ageing superstars prefer to go. As a result, the foreign superstars of ISL are not even the has-beens like Nicholas Anelka, they are the never-weres like Iain Hume, whose crowning moment as a professional footballer was three years at Leicester City when it was in England’s third division.

All of these leagues hope to convert India into a breeding ground of talent. However, with no real effort or changing things at the grassroots level, simply shelling out money to established national players only makes the leagues follow a ‘rich get richer’ model, hindering future development of talent. This, in turn, hurts the product. The IPL remains unaffected due to cricket’s strong grassroots mechanism, ensuring there is always a new Prithvi Shaw or Shubman Gill to look forward to in the coming season. Without this in place, leagues like the ISL have to pin hopes of their success on a fickle audience.

Integration programmes at grassroots level

As such, the owners and organisers must decide what exactly is the purpose of these leagues. For the IPL, the purpose is clear — take a sport that was already a money-maker, and turn it into this huge financial machine that is pumping out massive returns on a substantially large investment made at the beginning. If that is what all the other sporting leagues want to do, their investments need to be higher, for they are targeting sports that have traditionally a fraction of the fan-following cricket does.

The payback period will be much longer and they will have to be aware of this right from the beginning. Most of the leagues that drowned did so for reasons. Moreover, the talent needs to be marketed properly. This is where the PKL has come out trumps. It has invested in marketing the players, bringing out the traits of the top stars and giving them larger-than-life personas through the commentary and analysis.

But if the purpose of the leagues is to improve the grassroots level penetration of the sport, they must concentrate on that instead of trying to build a top-heavy league without the right base. That is where the ISL has suffered. In spite of its grassroots programme that aims at better development of budding footballers, the ISL has been in a soup with the AIFF and the I-League. Players have to choose one or the other, and with the I-League’s older and more established clubs having more effective grassroots programmes and talent-scouting abilities, the integration of young players has taken a hit.

Such infighting cannot exist between leagues, federations, organisers and so on if a proper grassroots penetration has to be achieved. The leagues must join hands with the government and try to build initiatives that help the youth train and also the general audience to connect more with non-cricket sports. Initiatives like ‘Khelo India’ have been started by the government but their effectiveness remains a question mark.

With a good amount of financial backing from league organisers and team owners, a bottom-up market penetration might be the answer for a sustainable future. The IPL model, when applied to other sports, will definitely find some success, garner some popularity and attract some eyeballs for a while, but it cannot be considered a solution for the long run.