- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How Indian forest-dwellers shaped urban economies of Asia

What is the role of the Indian upland forest-dwellers in the history of ancient and medieval trade? It may be difficult to give a proper answer to the question because there are only a few studies about the Indian forest-dwelling communities, which had once played a major role as key suppliers for the urban economies of Asia. Even though we have inscriptional evidence of ‘tribal’...

What is the role of the Indian upland forest-dwellers in the history of ancient and medieval trade? It may be difficult to give a proper answer to the question because there are only a few studies about the Indian forest-dwelling communities, which had once played a major role as key suppliers for the urban economies of Asia.

Even though we have inscriptional evidence of ‘tribal’ kingdoms that existed centuries ago, Indian forest-dwellers are considered ahistorical. Research on their past, therefore, is scant and inadequate. A five-member all-female team of international researchers is trying to shatter this misconception through a five-year-project. The aim of the Nilgiri Archaeological Project (NAP) is to move beyond the conventional view that sees south Indian upland forest-dwellers as secondary actors on the stage of global history, and change our understanding of the role that they played in the making of world civilisation.

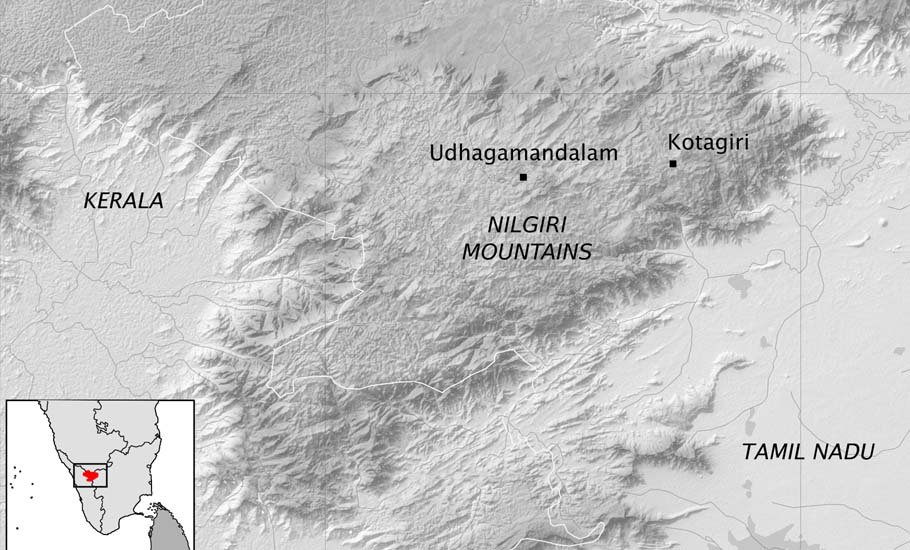

In an interview with MT Saju, the project’s principal investigator Daniela De Simone says it is likely that the past forest-dwellers of the Nilgiris played a key role in thriving Indo-Roman trade. She also talks about the methodology of her team and how the project will shed light on the history of forest-dwellers in the Nilgiris, a district in Tamil Nadu, bordering Karnataka and Kerala. The project focuses on the Nilgiri mountains, the homeland of at least 16 ethnic groups, which practice gathering and trading of forest products, swidden agriculture, pastoralism, and wage labour. NAP, according to Daniela De Simone, assistant professor of Indian Studies in the Department of Languages and Cultures at Ghent University, is an interdisciplinary research project involving several scholars from India and Europe who will investigate museum collections, the built and natural landscape, archaeobotanical remains excavated, early colonial herbaria and botanical literature, indigenous oral histories, and inscriptions in old Kannada and old Tamil.

Why are forest-dwellers being neglected in the records of history? What is the aim of NAP? And why did you choose the Nilgiris?

In the latter half of the second millennium BCE, Indian cities thrived on the extraction of upland forest products, feeding them into networks across South Asia, the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal. Forest products included plant materials and animal by-products, such as timber, medicinal plants, dyes, resins, ivory and wild honey, as well as metal ores and gemstones (a long list of forest products is found in the Kautilya’s Arthashastra). Forest-dwellers, with their ecological knowledge, became key suppliers in the urban economies of Asia. There is inscriptional evidence of “tribal” kingdoms dating to–at least–the fourth century CE as indicated by the praśasti (panegyric) in praise of Samudragupta composed by the poet-minister Hariṣeṇa and inscribed on an Ashokan pillar now in Prayagraj.

The inscription lists the names of several āṭavika rājas (‘forest kings’). However, Indian forest-dwelling communities are still perceived as ahistorical. Therefore research on their past is scant and inadequate. This is the result of a Eurocentric perspective that is still dominant today and relegates Indian upland forest-dwellers to the margins of history. The NAP wants to highlight that before British colonialism, forest-dwellers played a key role in the economic and political life of India. While pre-colonial textual evidence on the history of forest-dwellers is not abundant but somewhat extensive, material evidence is scarce. The Nilgiri region has been selected because of the unique richness of excavated assemblages and structural remains discovered in a forested area.

The NAP is a five-year research project (2021-2026) based at Ghent University, Belgium in collaboration with the Government Museum, Chennai, the French Institute of Puducherry (IFP), the National Institute of Advanced Studies (NIAS) in Bengaluru, and the University of Naples “L’Orientale”, Italy.

You once said, “Archaeological research in Indian forests is at an early and undeveloped stage.” Why is it so?

The scarcity of archaeological investigations in Indian forests is partly the result of the practical difficulties of carrying out research in those areas, but mainly the by-product of a colonial perception of the “hill tribes” or upland forest-dwelling communities as primitive, remote, and isolated, and therefore more properly the subject of ethnographic rather than archaeological studies.

You did a similar study when you worked with the British Museum three years ago, right?

When I was curator of the South Asian Archaeological Collections at the British Museum, I focused my research on the collection of Nilgiri artefacts brought to London by British colonial officers, in particular those excavated by JW Breeks in the early 1870s.

What are the challenges in this project? You had mentioned the problems during surveys conducted in the forest lands, so how are you going to deal with it? Are you planning any excavation?

We have no excavation planned. We will study museum collections, map the built and natural landscape, analyse archaeobotanical remains, review early botanical literature, record indigenous oral histories, and translate old Kannada and old Tamil inscriptions mentioning the forest-dwellers.

The team is developing specific methodologies to work in forest areas and we can count on the long and outstanding experience in carrying out fieldwork in the Nilgiri forests of our team members based in the Department of Ecology at the French Institute of Puducherry.

Could you please tell me a little about the nature of the survey and documentation?

The tops and ridges of the Nilgiri mountains are dotted with megalithic tombs excavated in the 19th century by the British, who also documented non-burial funerary monuments–such as dolmens and memorial stones. We will map the sites of burial and non-burial monuments of the area north of the towns of Udhagamandalam and Kotagiri, where most of excavated burial sites concentrate, to reconstruct the funerary landscape of the region. Site distribution will then be analysed to determine patterns of occupation and define the relation between burial and non-burial sites as well as between these sites and the surrounding environment.

Landscape features that can lead to the identification of settlements will be given special attention since the settlements associated with the funerary monuments of the Nilgiri mountains have never been discovered. We will also collect pollen and phytolith samples to reconstruct the early ecology of the study area.

Grave goods unearthed from the megalithic tombs are the only excavated evidence we have of the past Nilgiri forest-dwellers since settlements have never been discovered. The Nilgiri burial assemblages include ceramics, and terracotta, bronze, iron, gold and stone artefacts. The largest collection of Nilgiri grave goods is at the British Museum and I have already studied it. We will now analyse the other substantial collection, the one in the Government Museum in Chennai.

What are the subaltern studies and literature that you underwent before venturing into the project?

I have read a lot about the Chenchus of the Nallamala Hills in the Eastern Ghats after visiting the exhibition titled ‘Another India: Explorations and Expressions of Indigenous South Asia’’ at University of Cambridge in 2017. It featured Chenchu artefacts, especially musical instruments, collected in the colonial period and the photographs taken by the Austrian ethnographer Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf in the 1940s when I had just started working on the Nilgiri collection at the British Museum. The Chenchus is a Scheduled Tribe but they have not always been a marginalised community. An article by MLK Murty published in the 1990s provides textual evidence of Chenchu royalty and a long record of relations with the political entities that governed eastern India from the fifth century CE. Unfortunately, there are not many long-term studies of the history of Indian forest-dwellers since most publications focus on the colonial and the post-colonial period but hardly on ancient and medieval times.

Did the forest-dwellers play any major role in the Indo-Roman trade? Do you have any evidence to prove this?

The area of Coimbatore, at the feet of the Nilgiris, has the largest concentration of findings of Roman coins. It is likely that the forest-dwellers of the Nilgiris played a key role in the remunerative trade of forest products with imperial Rome. The Romans were exceptionally fond of Indian pepper and cardamom, and the gemstones from Coimbatore were particularly in demand in Rome. Therefore, it is likely that the past forest-dwellers of the Nilgiris played a key role in thriving Indo-Roman trade since they were the suppliers of these sought after forest products. The trade of forest goods continued into the medieval period but, this time, it was Europeans, Arabs and Chinese who came to India to acquire the ‘spices’. At that time, the port of Kozhikode was one of the key commercial hubs of peninsular India and it is only about 150 km from Udhagamandalam. The grave goods excavated from the Nilgiri megalithic burials include several luxury items that seem to have been imported from the coasts of Kerala and the plains of Karnataka. This seems to indicate that at least a section of the past forest people of the Nilgiris were well-off.

Please tell me a little about the field work? Your personal encounter with the people in the hilly terrain…

NAP started in September 2021. Unfortunately, because of the outbreak of COVID-19, we are yet to start fieldwork. However, I did conduct preliminary fieldwork in 2018 when I went to the Nilgiris to map the sites where the artefacts in the British Museum collection were excavated. Before I started working on the archaeology of the Nilgiris, my research focused exclusively on the archaeology of the Middle Ganga Plain, an area between UP and Bihar.

I had visited South India before but never worked in the region. However, I immediately fell in love with the culture and people of the Nilgiris. While visiting Tharnadmund, one of the Toda villages, the clan chief invited me and my colleagues from Chennai to a Toda wedding, it was a great experience since we are able to enjoy traditional singing and dancing as well as different ceremonies. While visiting another Toda village, a big boar came out of the forest.

My colleagues and I were a little scared but a Toda woman told us not to worry because the animals of the forests are friends and they will not hurt us. The boar had only come out to drink water from one of the ponds nearby.