- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How China's education system produces world beaters

For the past several years, China has maintained a high rate of growth in their GDP. From around 400 billion dollars in the 1990s, its GDP has grown to over 13.6 trillion dollars. Compare that to India, from around 320 billion back then, it has grown to only about 2.7 trillion. Despite having similar populations, China has galloped on the dollar rally. The difference has a lot to do with...

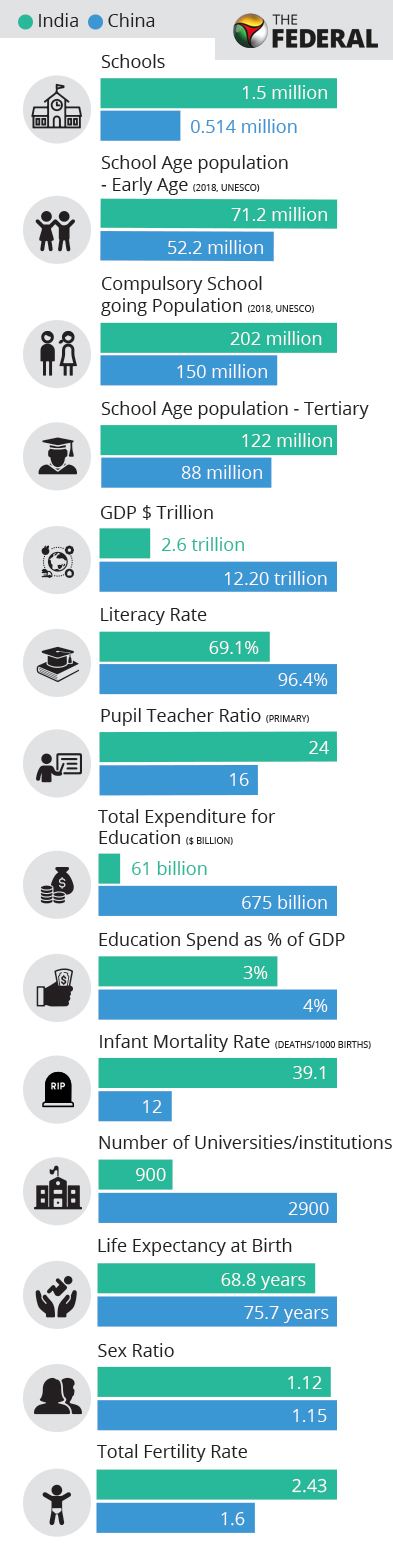

For the past several years, China has maintained a high rate of growth in their GDP. From around 400 billion dollars in the 1990s, its GDP has grown to over 13.6 trillion dollars. Compare that to India, from around 320 billion back then, it has grown to only about 2.7 trillion.

Despite having similar populations, China has galloped on the dollar rally. The difference has a lot to do with the aggressive competitiveness that the Chinese develop from a very young age.

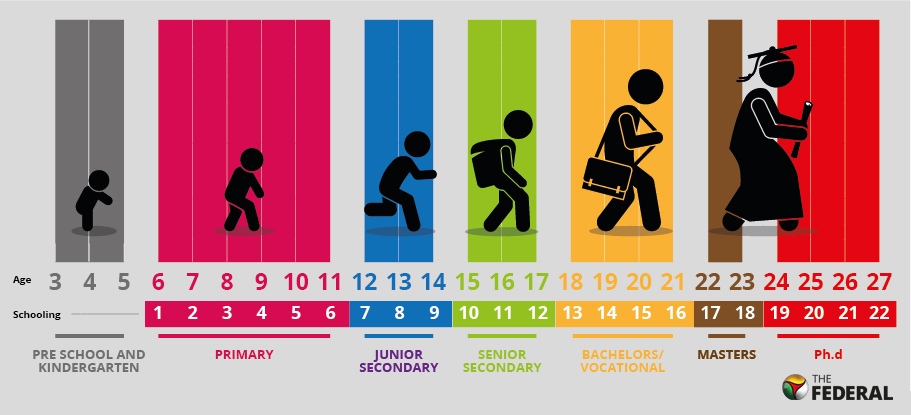

Unlike India, Chinese children have to undergo six years of school at the primary level, though a few urban school systems do use a five-year cycle. Following that, they have six years of schooling which are divided into two sets of three years.

Before the 1990s, for the first set of three years, secondary schools recruited students on the basis of an entrance examination. To emphasise the compulsory nature of junior secondary schools, and as a part of the effort to orient education away from examination performance and towards a more holistic approach to learning, the government replaced the entrance examination with a policy of mandatory enrolment based on area of residence.

After the government-mandated nine years of compulsory stint, Chinese students can choose whether to continue on an academic track with senior secondary education or pursue alternatives.

Senior secondary education takes three years. There are five types of senior secondary schools in China — general senior secondary, technical or specialised secondary, adult secondary, vocational secondary and crafts schools. The last four are referred to as secondary vocational schools and are considered as alternatives to the general senior secondary.

The great Zhongkao divide

For this, students at the age of 15-16 undergo a public examination called Zhongkao or High School Entrance Exam (HSEE) before entering senior secondary schools, and their admission to the higher class in different schools depends on the score in this examination.

China is obviously extremely competitive and therefore in order to balance the country’s limited educational resources and to meet the needs of a changing global labor market, China’s Ministry of Education has dictated that the pass percentage of students taking the exam will be only 50 per cent, that is, only top-scoring half will go through while it has been pre-determined that the lower-scoring half — no matter how hard test-takers try — will only have the option to go to vocational school. There are no alternate paths for them to receive a university four-year degree once they move out of the academic track.

The test is crucial in determining the academic trajectory of students’ lives. Those who fare poorly in the HSEE will either drop out of school or choose to study in a vocational or technical secondary school. The divergence in destinies due to this single exam can be stark.

As a result of this, the “test prep” market or coahing classes that help students clear the Zhongkao is very large and some teachers are treated like Rock Stars with cut outs of them placed outside these classes.

Gaokao: Ticket to secure future

Almost three years after Zhongkao, after completing secondary education, comes the Gaokao or National College Entrance Examination, for admission to China’s universities.

The Gaokao, intended to level the playing field between the country’s rich and poor, is an extremely tough two-day exam which ranks China’s high school students, totaling around 10 million, according to their score.

Each year, in the beginning of June, millions of students take the Gaokao. Scored on a scale of 750 points, with questions varying from province to province, the Gaokao generally includes tests of Chinese literature, mathematics and a foreign language (in most cases English).

The performance of a student in the Gaokao has been proven to have a strong correlation to their future chance of employment and expected income, a fact that most Chinese families know very well, and that creates an annual epidemic of test preparation which includes intensive studying, stress, apprehension and fear as the Gaokao dates in June, approaches.

‘Illegal’ Gaokao migrants

Due to the high-stakes nature of the examination, students and families go to the extreme to ensure success. Some become “Gaokao migrants”.

Gaokao migrants refer to students who leave their hometowns and migrate to smaller cities or towns just a few days before the exams in order to get bonus points or take the exams in a less competitive environment, thereby securing an advantage over their peers.

This is because of a loophole in the education system. To make up for the lack of uniform distribution of educational resources across the country, the Chinese education system incentivises universities and colleges to enroll students with different Gaokao scores from different Gaokao test centres.

This means that the state’s demographics can affect how each province’s students performance is taken. A student’s results in the Gaokao are heavily weighed by the population density of the provinces, overall economic development in the province and how successful their entrants have been in the past.

Although it is organised at the same time nationwide, the test is administered at provincial levels.

The phenomenon of Gaokao migrants is not a new one, and similar incidents have been seen frequently in recent years.

Although local policies usually restrict candidates to their hukou (household registration) provinces, some candidates, lacking hukou, become “Gaokao migrants” and attend the Gaokao.

In recent years, some provinces have also relaxed norms for migrant children taking the Gaokao. Guangdong, which has the most relaxed policy, has the most number of students taking up the exam. Migrants here can take the exam if they have completed three years of high school in the province and their parents have legal jobs and paid for three years of social insurance.

However, in the last few years, following protests from local population, provincial governments have started a crackdown on illegal Gaokao migrants and in some provinces, even disqualified candidates.

History of examination obsession

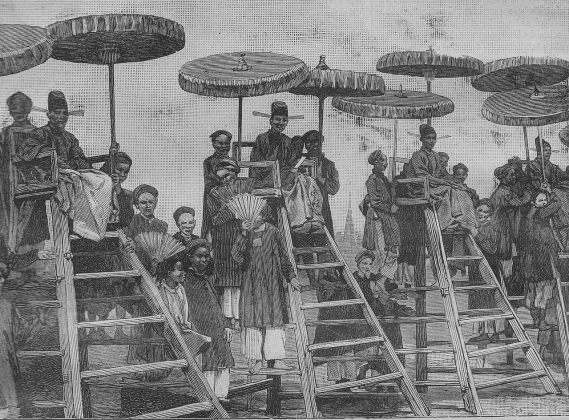

For more than 1,200 years, anyone who wanted a government job in imperial China had to pass a very difficult test. This system ensured that government officials who served in the imperial court were learned and intelligent men, rather than just political supporters of the emperor, or kin of officials.

Based on historical documents, one could conclude that ever since the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD), Chinese people have exalted and glorified those who score well in competitive examinations. Much like today, doing well in the imperial exams meant a job in the royal court which then assured societal respect and often meant working directly with emperors and nobility. While the imperial system — and the imperial examinations — came to an end in 1905, China, culturally, has clung on to its obsession with exams, and mastering them.

The idea of meritocracy

In theory, the imperial examination system which offered an entry into the Chinese Civil Services, from the days of the emperors, ensured that the government officers would be chosen based on their performance in a common exam and not rely on their family connections or wealth.

A peasant’s son theoretically could pass the exam and become an important high official if he worked hard and prepared for the exams. However, in reality, a poor youth would need a sponsor (wealthy or nobility). However, just the possibility that a peasant boy could become a high official was very unusual in the world at that time when compared with contemporaries.

This has resulted in a high level of competitiveness among the people, and also created the “Gaokao migrant” trend. However, China’s rigorous system has also resulted high GDP growth and made the world sit up and take note.