- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How a Kurnool eatery’s Kunda Biryani comes close to challenging the might of Hyderabadi Biryani

On June 11, I happened to be in Kurnool, a city located on the right bank of river Tungabhadra, for some work. I was passing by National Highway 44, 225 km from Hyderabad with my wife, with an overriding thought of having a special lunch. What is a Sunday, after all, without a special lunch? I began making calls to journalist friends who are foodies and familiar with Kurnool, capital of...

On June 11, I happened to be in Kurnool, a city located on the right bank of river Tungabhadra, for some work. I was passing by National Highway 44, 225 km from Hyderabad with my wife, with an overriding thought of having a special lunch. What is a Sunday, after all, without a special lunch? I began making calls to journalist friends who are foodies and familiar with Kurnool, capital of erstwhile Andhra after it was carved out of Madras in 1953.

My request was simple — suggest a place that offers food which is unique to Kurnool. Surprisingly, all of them pointed me to the same eatery — Prasada Reddy’s Kurnool Kunda Mutton Biryani (KKMB).

The suggestion left me in a dilemma. While I trusted the advice of the people I had called, being a Hyderabadi, eating biryani outside of Hyderabad was not a natural choice for me. For Hyderabadis, any biryani which is not from Hyderabad is inauthentic, if not outright fake.

I was particularly apprehensive about having biryani in Kurnool, often referred to as the Gateway of Rayalaseema. Though the city had been under the influence of nawabs for centuries, it did not develop a distinct food culture like that of Hyderabad. The district that houses Shaivite shrines like Srisailam, Mahanandi, Ahobilam, Yaganti and Mantralayam Mutt, has preserved its unique Rayalaseema flavour. Though biryani became a popular food choice about 20 years back, it could not resist being regionalised in this part of Rayalaseema.

Keeping my apprehensions aside, I decided to heed to the advice I had received. If making the choice was difficult, getting inside KKMB wasn’t going to be any easier. When I reached Reddy’s Kunda Biryani joint, sandwiched between shops on Nandyal Road, I saw a long queue in the waiting.

After a wait of about 30 minutes, which felt like eternity given how hungry we were by now, I was told I could walk in by the manager. We were pointed to a table by waiter who was efficiently taking orders, keeping an eye on tables about to be vacated and also laying food for those who had managed to grab a seat. The four-five waiters were all working in the same manner.

With trepidation, I placed my order for Kunda Biryani (pot biryani), and as the waiter headed to the kitchen to get my order, I used the time to quickly look around. Around 50-odd people were seated inside. Some had come with families, some were with friends and some alone. As those inside were relishing their meals, people outside were peeping into the air-conditioned dining hall from all corner to check which table was being vacated to grab a seat.

In about 15 minutes, the much sought-after Kunda (clay pot) arrived on a tray decorated with raita, onions and shorba. The bearer turned the Kunda upside down with utmost caution as the piping hot dish and the pot ran the risk slipping and spilling on the ground. He emptied the pot onto the tray, mixed it well and served it on the plates before signalling us to start eating.

Lo and behold, KKMB turned out to be an extremely delicious stuff even though it did not resemble the Hyderabadi Biryani in colour and texture. Much as I wanted, KKMB was a completely localised version of biryani. The mutton pieces were so soft they melted in my mouth. The rice was also optimally cooked and the whole combination offered an assertive flavour. The rice used was not biryani which is normally used for Hyderabadi biryani.

A pot of mutton biryani costs Rs 650 and serves two.

Reason for distinct quality

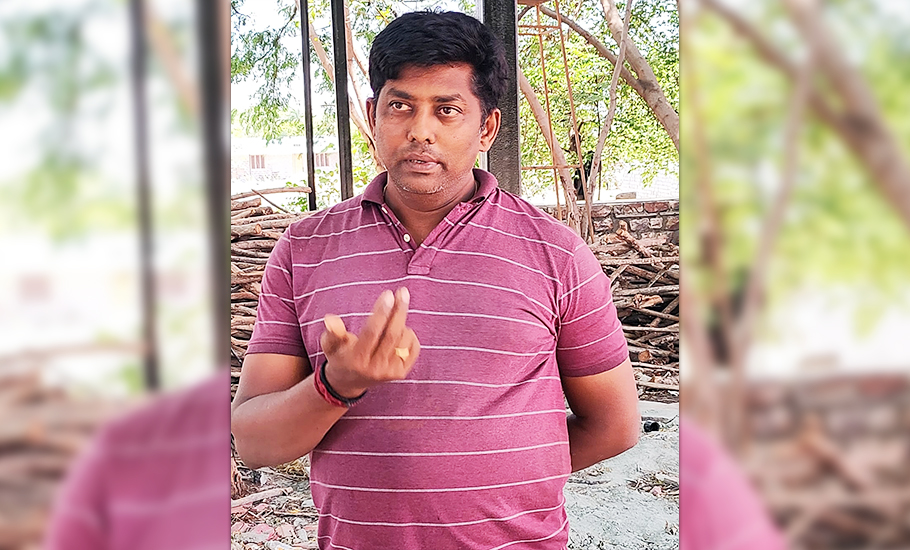

I was so impressed and intrigued by Kunda Biryani that I asked the waiter to introduce me to the cook. To my amusement, I found the cook was also the owner. Prasada Reddy Yalluru was more than willing to share the secrets of his biryani with the simple condition that I offer him an impartial feedback. Despite the heavy rush, Reddy took us around the kitchen to introduce us to the process of cooking KKMB.

“For KKMB, we use no special spices other than those used in Kurnool district for cooking regular food. The biryani masala powder is simple and prepared at home, under the supervision of my mother and wife. No masala mix is bought from shops. Ghee is used optimally. People of all age groups should eat our biryani without any fear of adding calories,” Prasada Reddy, the farmer-turned-cook, told The Federal.

Though ghee is critical to preparing Kunda Biryani, surprisingly, you don’t find any trace of oil or ghee when the dish is served.

“The biryani takes the flavour from the ghee and sends out the fatty portion as vapour through a small vent at the brim of the pot. Special care is taken to drain out the leftover ghee. If you allow even a drop of ghee to remain at the bottom of the pot, it leads to over-cooking,” says Prasada Reddy. A person checks the pot for any trace of oil or ghee by tilting the pot before serving. If he finds even a single drop of ghee, it goes for the second round of ‘dum’.

Fresh mutton is key

The mutton used in the preparation is fresh and is not bought from local shops. Reddy’s venture has its own sheep. The animal is cut only when the order comes from the kitchen. Raw mutton is not stored in the fridge even for a few minutes. “Meat from the freshly cut animal is used immediately before getting exposed to light and air,” Reddy said.

“These two elements ruin the taste and rob the meat of its colour and texture. Fresh meat would not only make the dish shine but also impart a lingering taste,” explained Prasada Reddy.

What makes KKMB unique, apart from the simple spices, is the quality of the mutton. “The sheep are carefully chosen and they are 100 per cent free range, which means they are not given any steroids. They are on display at the restaurant. Everything is transparent at the eatery. One can watch every step of the preparation,” he told The Federal.

Bumpy road to perfection

Reddy, now 40 years old, says it took five-six years to attain perfection after hundreds of trials and errors. Till the time, Reddy did not get perfection in his cooking, he would prepare the biryani and distribute it free of cost to hostels and orphanages. Each day, he would learn something new in the process.

“We spent a lakh every month even though we were not sure of business,” he said.

After two years of experiments, Reddy started selling Hyderabad-style biryani. As competition was intense in the biryani sector, it did not stand out. So, he switched to Kunda Biryani and experimented for months to find a suitable kunda (clay pot), the right quantity of masala, ghee and the quality of the mutton. Finally, he succeeded.

“The way it is cooked, if you don’t remove the seal, it would remain fresh for six-seven hours without any need for storing it in the fridge. We sell around 400 pots every day, including a few pots of chicken biryani. Outside Kurnool, Bangalore is KKMBs preferred destination which falls in the range of six-seven-hour journey,” he said.

How the farmer became the cook?

Reddy entered the biryani business, a completely new field, as farming became unprofitable in his village of Bollaram. The village located close to Kurnool city was once known as the Naxalbari of Kurnool district.

The crisis in the farm sector forced his family to search for alternative livelihood options. His parents migrated to Kurnool 20 years back. His father’s foray into the milk business did not succeed. So, Reddy thought of something new. He was amazed by the buzz of biryani which started about 15 years ago and wanted to try his hands.

“We invested all the money into the new trade much to the opposition of our family members. We sold land and borrowed money at exorbitant rates of interest to stay afloat and consequently we reached bankruptcy at a point of time. Friends and relatives warned us to quit before it was too late. There were moments of doubt. For months, we slept on the floor of the shed with workers without going home. The invention of KKMB was the turning point,” Madhusudan Reddy, Prasada Reddy’s brother, who is now a techie in Hyderabad.

Touching the feet of workers

Now Sri Divya Kunda Biryani, though popular as Prasad Biryani, is a brand in Kurnool city. But Reddy was humble enough to attribute it to the collective endeavour of all employees of the hotel which now has 35 members. The business owes as much to the employees as it does to the owners. He wishes for the dedication of employees to continue and takes their blessings.

He touches the feet of every worker on Dasara day stating the quality and popularity of KKMB are not possible without their dedication. “They are my tools and weapons. So, on Vijayadasami day, I touch their feet and take blessings from them by presenting a Rs 10,000 check and dress. It’s my Ayudha Puja (weapon worship).

Asked what’s next, Reddy says that he plans to open a huge restaurant outside the town based on the typical Kurnool rural setup where everything is cooked using firewood and charcoal. “Cooking with firewood is altogether a different experience. We want to take the cooking techniques back to the 1950s and 1960s when cooking gas was unknown to replicate the same taste,” he added.