- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Guns, graves and grief: Kashmir frozen in time

Nearly a week after her son Zubair Lone was buried at a sprawling cemetery—designated exclusively for militants—Sara Lone couldn’t take it anymore. Walking through a thick carpet of snow on January 4, she came out to demand that his body be returned to the family. “I don’t know what they did to him?” a wailing Sara told newsmen at Srinagar’s Press Enclave during a protest staged...

Nearly a week after her son Zubair Lone was buried at a sprawling cemetery—designated exclusively for militants—Sara Lone couldn’t take it anymore. Walking through a thick carpet of snow on January 4, she came out to demand that his body be returned to the family.

“I don’t know what they did to him?” a wailing Sara told newsmen at Srinagar’s Press Enclave during a protest staged by the families of three youths killed in an alleged fake encounter in Lawaypora on Srinagar-Baramulla highway on December 30.

Twenty-two-year-old Zubair, along with two others—Athar Mushtaq Wani, 17, and Aijaz Maqbool Ganai, 21—fell to army bullets in an abandoned house in Lawaypora.

Their families, however, allege that the encounter was fake.

“I don’t want anything except my son’s body,” says Sara.

Locals claim they saw army officials searching the abandoned house a few days before the ‘encounter’. “They even questioned several locals living near this house,” said a local.

After the “recce”, as locals call it, the alleged encounter started on the evening of December 29, without cordoning off the area or warnings to the locals.

“Suddenly, a contingent of army men arrived and started firing at the house,” said a local shopkeeper. “Soon everything was shut and the traffic stopped. The firing continued till midnight.”

After the encounter

Once the guns fell silent on the morning of December 30, pictures of the slain youths started doing rounds on social media. Soon Sara, along with her family members, rushed to Srinagar, 45 km away. Outside the police control room (PCR) in Srinagar, she wailed for her son for hours.

Later, she travelled another 70 km to reach the graveyard in Gund, where Zubair and the other two were to be buried.

After reaching the graveyard following several rounds of permissions and crossing many checkpoints, Sara finally saw her son’s naked body. She hugged him hard while her two other sons dug the grave.

Two of Zubair’s brothers are in J&K Police. One of them has prepared graves for several militants in Gund. This time, he was preparing a grave for his own brother who was buried at night in the presence of a few family members.

Earlier in the day, around 9:30 am, it was Maqbool Ahmad Ganai, a policeman posted in Ganderbal area, who received a call from Rajpora police station asking him to send a photograph of his son—Aijaz. He sent the photograph but got suspicious and rushed to Srinagar, where he was told that his son was killed in the ‘encounter’.

“I wasn’t allowed to go inside the PCR until I showed my police identity card,” says Maqbool who went in and saw the naked body of his son.

Maqbool, who has often escorted bodies of militants to be buried in Gund, complains that there were no proper arrangements for the last rites and burial at the graveyard.

Around 11:30 am that day, Mushtaq Ahmad Wani, who was in Srinagar to drop off a trader at the airport, got a call from Rajpora police station in Pulwama, asking the whereabouts of his son, Athar. He panicked and drove fast towards his home, where he saw scores of neighbours gathered.

By now, it was clear that something had gone horribly wrong. The family had been informed that Athar was killed in the ‘encounter’. They rushed to Srinagar PCR, as they were told that the three bodies were brought there from the ‘encounter’ site. The families of the other two had also reached the PCR by now.

“I was permitted to see the body of my son at the PCR briefly and then they took him away in an armoured vehicle…” says Mushtaq. “My son had bullet injury near his heart and injury on head near his left ear.”

Mushtaq, after initial confusion about the location of the grave, drove towards Gund along with his mother, wife and daughter.

After being stopped at several checkpoints, they reached the spot. He saw Athar’s body lying on the floor of the police vehicle along with the other two bodies. They were directed to take them down to the graveyard on a wooden plank. He says all of them were naked and they somehow managed to get shrouds for them.

The J&K Police had dug two graves with an earthmover that stopped functioning while digging the third. A single bulb was the source of the light in the dark freezing night, which was switched off during the burial. They then used mobile phone light to complete the last rites. “I filled the grave with soil and snow,” says Mushtaq.

Allegations and counter-allegations

The families’ allegations come close on the heels of Jammu and Kashmir police filing a chargesheet against an army captain and two civilians for allegedly abducting and murdering three labourers in a staged gunfight at Shopian’s Amshipora back in July. Both the army and the police had earlier claimed that the three slain labourers were “unidentified militants”.

So, is Lawaypora another Amshipora? The Army says no.

HS Sahi, general officer commanding (GOC), Kilo Force, on December 30, said that the army had been getting inputs over 10 days before the encounter about the presence of a group of militants in the area.

“On Tuesday (December 29), we got specific inputs that three militants are in a house right opposite to Noora hospital at Lawaypora in HMT area on the Srinagar-Baramulla highway,” he had said.

The three militants, he said, had plans to carry out a “big strike” on the highway and that they had turned down repeated surrender offers both on Tuesday evening and Wednesday morning.

J&K Police chief Dilbag Singh, while addressing a presser in Jammu, said he had no reason to contradict the army’s statement, but investigations would be carried out into the families’ allegations.

“Two of them are hardcore associates of militants (also known as overground workers or OGWs). One of the two (Athar) is the relative of a top HM commander, Rayees Kachroo, who was killed in 2017. Reportedly, the third might have joined very recently,” the police said in a statement, adding that generally parents don’t have an idea about the activities of their children.

In another statement, on January 1, the J&K Police said it has details about the mobile tower locations of the slain youngsters.

“Contrary to the claims of Aijaz’s family, the verified digital evidence revealed and corroborated that Aijaz and Athar had gone to Hyderpora and from there to the place of occurrence only,” the statement said. “Antecedents and verifications too show that Aijaz and Athar were radically inclined and had aided militants of the LeT (the so-called The Resistance Front now) outfit. Nevertheless, police are investigating the case from all possible angles.”

But neither Sara nor the families of the other two slain youths are buying the official version of the events. It’s been more than 10 days since but time seems to have frozen for the three families who are searching for an answer.

According to Zubair’s mother, he was home till 2pm on December 29.

Zubair used to run a shuttering business and employed around 15-25 non-local labourers for different projects. He earned around ₹30,000-35,000 every month.

“After lunch, when he put on new socks, I told him, ‘These are beautiful socks, can you buy them for me as well?’ He smiled and promised to buy me new socks,” she recalls. After this brief conversation he left home for a stroll as he was not working that day.

Some of his neighbours too claim that they had seen Zubair in the village around 2:30pm on that day.

However, according to the J&K Police’s January 1 statement, Zubair had gone first to Pulwama, around 13 km from his home on December 29, then to Anantnag, around 40 km away, then back to Shopian, around 35 km from Anantnag, before finally coming to the place of encounter in Srinagar, which is around 45 km away.

Covering such a long distance is impossible in the mountainous terrain of Kashmir within a short time, his family members contend.

Moreover, Riyaz Lone, Zubair’s elder brother says, “Between 4 and 5 pm that day, Zubair informed our brother Abid that he would stay at his maternal uncle’s home in Turkwangan village. There was nothing unusual about it.”

“Police maintain records of even those who are accused of throwing a single stone at them,” says Riyaz. But Zubair had no previous record of involvement in any case related to law and order or militancy, he adds.

“Did they have any input about my brother’s so-called association with any militant organisation? If he was a militant, why didn’t they call us at the encounter site, as they usually do, and seek our help to disarm and make him surrender?”

The police later released two videos of the night of December 29 — showing the army making surrender appeals to the three youths killed inside the abandoned house.

Budding interior designer

A few kilometres from Tukwangan is Bellow village in Pulwama. Athar roamed in the alleys of this village on December 29. Several neighbours saw him that day.

His father, Mushtaq Ahmad Wani, has threatened to commit suicide if his son’s body was not returned and allowed to be buried in their native graveyard.

A video of Mushtaq digging a grave for his son in his village, around 35 km from Srinagar, went viral on social media. The grave is waiting for the body, which is buried scores of kilometres away.

“My son was a juvenile… he was innocent… he was tortured and murdered mercilessly,” says Mushtaq. He further cautions, “If you have to live with India, be ready to lose sons like Athar… Today I lost my son, tomorrow it will be someone else’s turn.”

He then congratulates the families of armed forces who he alleges “kill innocent kids for money, medals and promotions”.

Athar, a Class 11 student, who was to appear in his last exam paper on December 31, had recently designed his family’s new house constructed in the lawn of their old house. “He was full of life and drawn to designing. Joining militancy was out of question for him,” says Zarka Mushtaq, Athar’s sister.

Recalling the last phone call, Zarka says they had a conversation for 23 seconds around 3:59 pm on December 29.

“Athar said he was in Srinagar with a friend and would come back home a little late…,” she says. “He had also informed me that his iPhone’s battery was dying and not to worry.”

At 5 pm, Zarka tried to call him again, but his phone was switched off. Family members continued to call on his number several times.

Zarka’s family has several unanswered questions. “If the army had inputs about the attack, why did they wait for my brother’s Srinagar visit despite having a massive surveillance at their disposal? If my brother and two others were carrying ammunition, as the army claims, why didn’t they blow the entire structure like they usually do in routine encounters in Kashmir? And if they did track him in that abandoned house, why weren’t we called to make him surrender? Why did they just call us to break the news of death?”

Policeman’s son

On December 29, Aijaz Maqbool Ganai, 21, got up from a month-long bedrest that doctors had advised due to pain in his leg.

He had tea around 10:30am and left home in Putrigam area, informing his mother Haseena that he had some work at the university in Srinagar. He was studying BSc final year at Degree College in Pulwama.

A day later, Haseena saw him lying naked in the PCR, Srinagar. “When I asked them where his clothes were, they told me they were burnt in the encounter,” says Haseena. “He had injury marks on throat, right shoulder, near heart and both arms.”

His sister Asiya had last talked to Aijaz over the phone around 3:30 pm and later his mother had called him around 4:00 pm asking him to come back as his leg pain could aggravate due to severe cold. Then a few minutes later, around 4:40 pm, his phone was switched off.

“If my son was a militant or OGW, then why did the local police and army have no idea about it?” asks his father Maqbool.

He recalls that a few days back in the last week of December, armed forces cordoned their village for a raid.

“They took Aijaz to identify and get inside the house which was to be raided. If he was an OGW or a militant, then why didn’t they detain him then,” asks the mournful father.

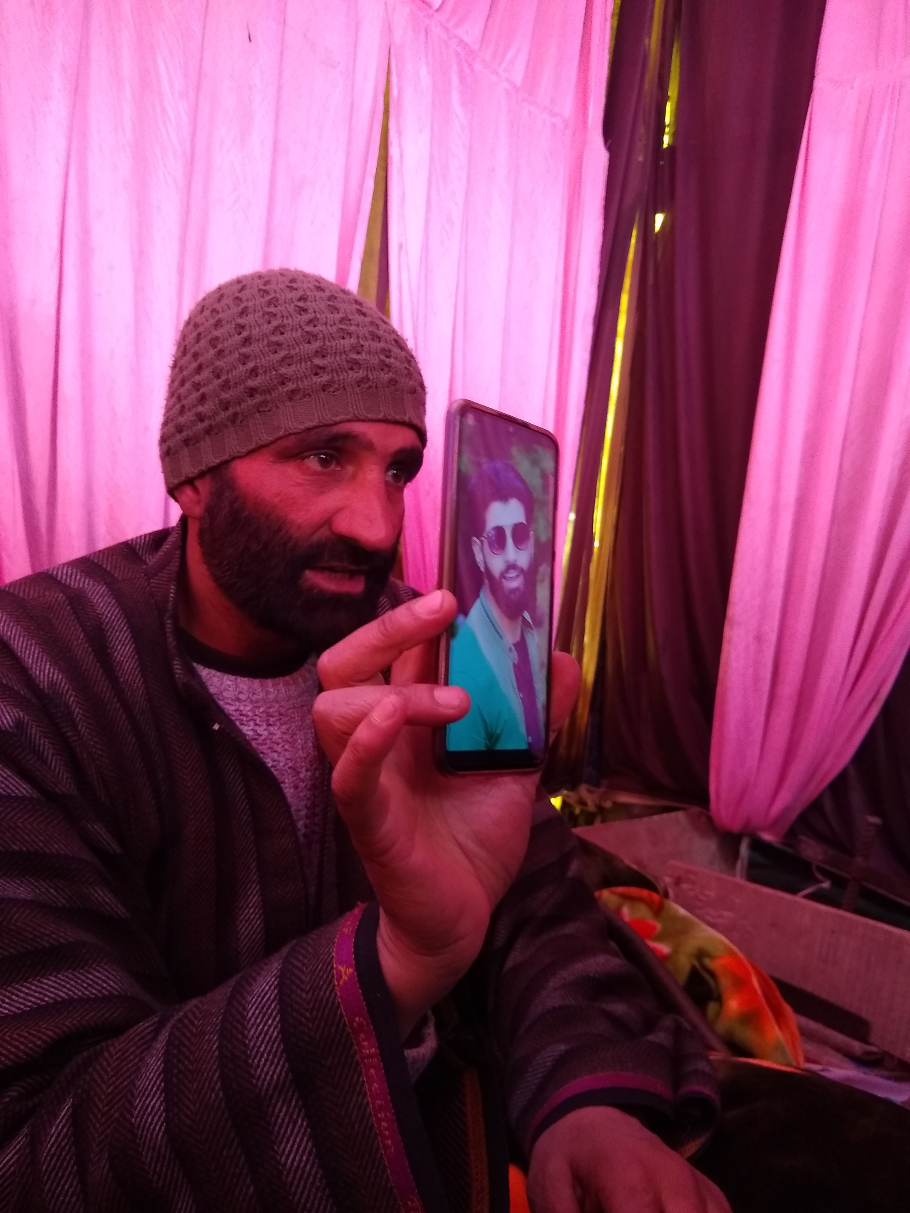

“Militants call their family when they are trapped in an encounter,” says Ghulam Muhammad Lone, father of Zubair. Had he been militant, he would have called us at least once, says Lone.

“He didn’t call because he wasn’t a militant…Maybe his phone was snatched or he was kidnapped. They plucked a rose from my garden. I want justice.”

Demand for return of bodies

Amid the frozen turbulence of the Valley, the fresh killings have only renewed the familiar pitches of “fair probe” and “justice”.

Among others, Kashmir’s beleaguered unionists have thrown their weight behind the campaign for justice.

But after petitioning the Raj Bhavan for speedy justice, the families are now braving cold and snowfall to demand the return of bodies.

As part of a new counterinsurgency policy started by the J&K Police amid the COVID-19 pandemic, bodies of local militants are not handed over to their families but are buried in faraway Ganderbal district.

According to police, around 160 militants have been buried at isolated places in 2020.

But locals see this policy as an attempt to deny the family members the right to mourn and bury their dead in the place of their choice.

In the past, bodies of militants who hailed from Kashmir were handed back to the families. The burial in their native villages would see thousands gather, chanting slogans against the authorities.

Amid the snowfall, the demand of the families — spurred by a hashtag #ReturnTheBodies written on a wall with snow — has only grown in Kashmir as well as on social media.

During the protest at Srinagar, Sara raised several questions and screamed for answers. But after the cops dispersed the protesting families, she returned home heartbroken.

She shudders recalling that dark night of December 30, when she was wiping the blood oozing out of Zubair’s head with her scarf.

Sara says she intends to keep the blood-soaked scarf with her as a final souvenir in remembrance of her 22-year-old son.

“This scarf is the companion of my solitude and the blood on it knows the truth of Zubair’s innocence.”