- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

From telegram to e-mail, how India Post managed to remain relevant

Post offices have evolved over the ages to cater to the new needs of the new ages, but experts feel it could have become local internet service provider and acted like moving ATMs, especially in a time of crisis like this.

It was September 23, 1990. In the wee hours of a Sunday morning, my grandfather R Margan (Margabandu), an octogenarian, fell off the verandah at his home in Rattinamangalam village Tamil Nadu’s Arani taluk. Soon after, he somehow felt his days were numbered. Back then, there were no telephones in the village. But he had to send out a message to all his daughters and sons living in...

It was September 23, 1990. In the wee hours of a Sunday morning, my grandfather R Margan (Margabandu), an octogenarian, fell off the verandah at his home in Rattinamangalam village Tamil Nadu’s Arani taluk. Soon after, he somehow felt his days were numbered.

Back then, there were no telephones in the village. But he had to send out a message to all his daughters and sons living in different cities.

The small room next to the verandah that he had rented out to the village post office for nearly two decades came as no help. One, it was a Sunday. Moreover, the Department of Telegraph was carved out as a separate wing from the Department of Posts in 1985. So, one had to approach the telegraph department to send telegrams and this office was located 3 km from the village.

With the help of a fellow villager, he sent out a message from the town office. As he felt odd to send the message himself, he asked his wife to be the signatory.

Harbinger of bad news

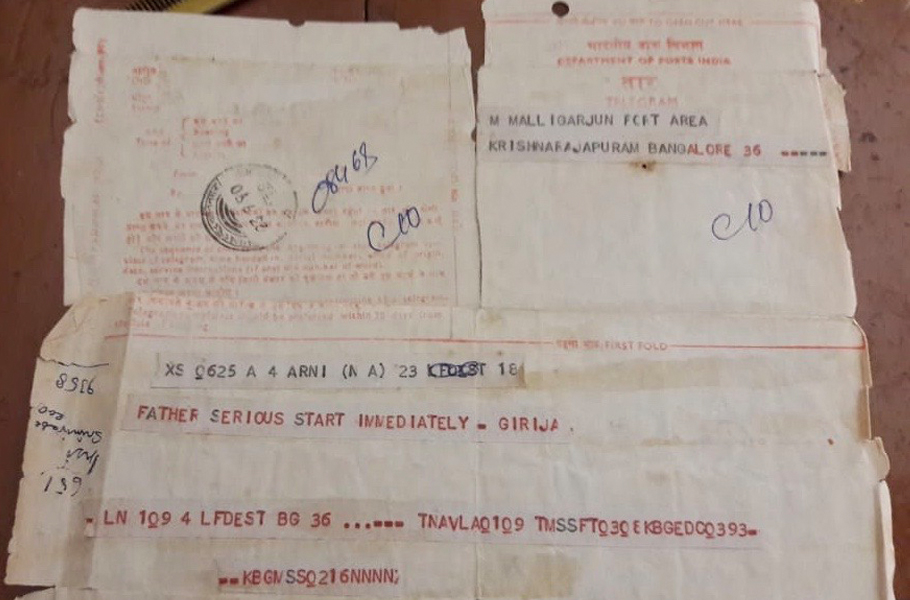

The message was sent at 6.25 am. Before the telegram could reach Bangalore, one of the relatives who lived near the village and received it first, made a telephone call from a public booth and passed on the message to others. But the message was passed on as “someone” in the village was serious.

Thinking that it could be my grandmother, my father left the village after informing my mother. About half an hour later, the tinkling of a bicycle bell indicated the arrival of bad news. In those days, telegrams were deemed to be the harbinger of bad news. When my mother received it, she wasn’t entirely shocked since she had an idea of what was coming.

“FATHER SERIOUS START IMMEDIATELY. GIRIJA.”

The only thing that the telegram made clear, beyond the telephone message, was that it was my grandfather and not my grandmother who was serious. My mother, too, left for the village.

By the time they reached the village, my grandfather had died. And the day before he died, he had withdrawn the rent that he earned from the post office — ₹10 every month back then — that he used to deposit in the post office’s savings account only. The money was used for his last rites.

Even though the telegram service was at its peak in the mid-80s, it somehow failed to serve its purpose of reaching people quickly. Or perhaps it faced competition from the telephone with the creation of the Department of Telecommunications in 1985. By the early ’90s, landline telephones had made its mark in cities.

People used postcards for short and crisp messages, an inland letter for lengthier messages. And an envelope meant an-almost lavish indulgence. With the advent of e-mails and mobile phones, the need for postal cards and inland letters reduced over the years. But that did not mean the postal department had become redundant. With the increase in population, the volume that each postman handled, in fact, increased over the years.

A journey down the memory lane

HR Gopinath, a postman working at the General Post Office, Bengaluru, says he joined the service when he was 19. After working as a contractual employee for two years, he got a permanent posting at the GPO in 1989.

In the later years of his service, he purchased a bicycle on a loan given by the postal department. As the money was deducted from his monthly salary, he says he did not feel burdened.

“We were happy to roam around on a bicycle. We enjoyed interacting with people, the smile on people’s faces when we delivered the mails kept us going for years,” he says.

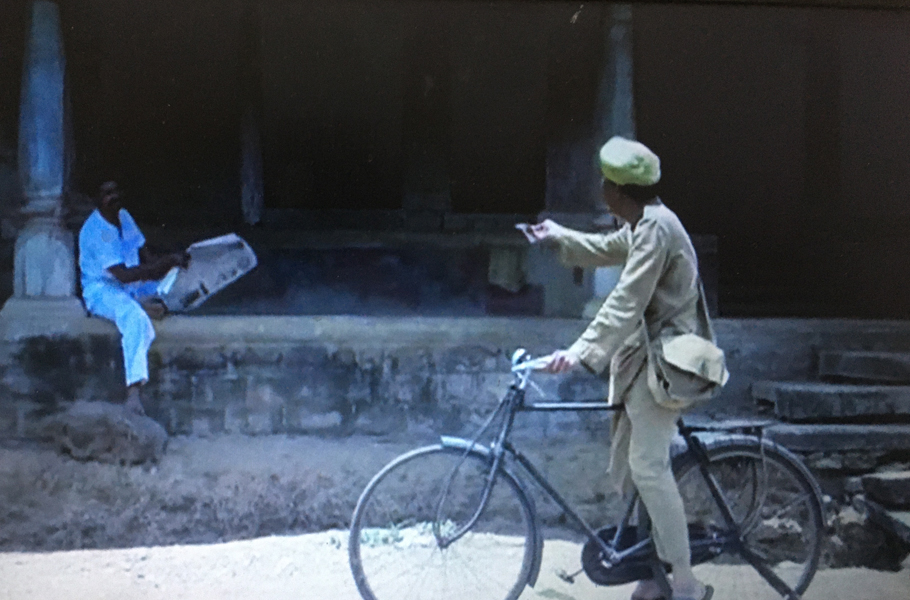

However, he also recalls the dreaded look on people’s faces while delivering telegrams, which often meant bad news for the receiver. Occasionally, there were happy messages that the telegrams carried — the birth of a child, news of a new job, etc.

Two decades ago, Gopinath used to make two trips every day, one in the morning between 7 am and 11 am and another between 3 pm and 5 pm. Now, postmen work a single shift from 8 am to 4 pm. He says while he delivered about 15 mails every day in the ’80s and early ’90s, now he does close to 120 deliveries — from posts to parcels and money orders and government documents. And his salary increased from ₹137 per month to almost ₹1,200 a month in a decade’s time as the telecom revolution began.

The native of Narasimhapura in Chikkamagalur district says he had seen the village postman and always wanted to be one. “I remember the look of anticipation on people’s faces every time the village postman would stop by their doorstep. I used to find it fascinating.”

The missing mail

Gopinath’s story somewhat resembles the life of Thanappa, the postman from RK Narayan’s Malgudi Days that was later adapted into a television series directed by the late actor Shankarnag.

‘The Missing Mail’ chapter depicted how Thanappa conversed with villagers and built a friendly relation with each customer he delivered the mails to. From delivering a message to a man who eagerly awaits a prize money for the crossword puzzle, to informing a woman about the birth of her grandchild and delivering money order and job applications, Thanappa did it all with ease moving on a bicycle.

Of all his contacts, he shared a cordial relation with the family of Ramanujam, a revenue officer in the village. The story goes on about how he hid a telegram informing the death of Ramanujam’s uncle fearing it would postpone his daughter’s marriage.

Thanappa delivers the telegram 15 days later and says, “You can complain if you like, sir. They will dismiss me. It is a serious offence.” But Ramanujam felt sorry that he had done this but never intended to complain.

The RK Narayan story is one that most Indians would cherish for long, nostalgically recalling the good old days of telegram.

Changes over the ages

“Although the telegraph department was bifurcated from the Departments of Posts, it remained a sister concern for many years and their staff took help from us to deliver messages,” says Gopinath.

On July 31, 1995, the day India’s first phone call was made on a mobile device, it cast a shadow on landline telephones and telegrams. The proliferation of mobile phones in the late ’90s, SMSes and e-mail, was to sound the death knell to postal services.

But Gopinath says they never felt threatened by the technological changes as the department kept increasing its services to cater to customers’ needs.

From a mail/parcel dispatcher, it turned into a part-banking institution, facilitating money orders, operating savings accounts and providing people life insurance schemes.

Besides, they delivered newspapers and magazines and also assisted in ensuring social welfare benefits such as delivery of MNREGA wages, issue of Aadhaar and PAN cards, and pension payments.

The telegram services were to be stopped in 2008 (by which time the Department of Telecommunications had taken over the Department of Telegraph) after no customer opted for the service for a full year.

It was officially brought to an end in 2013.

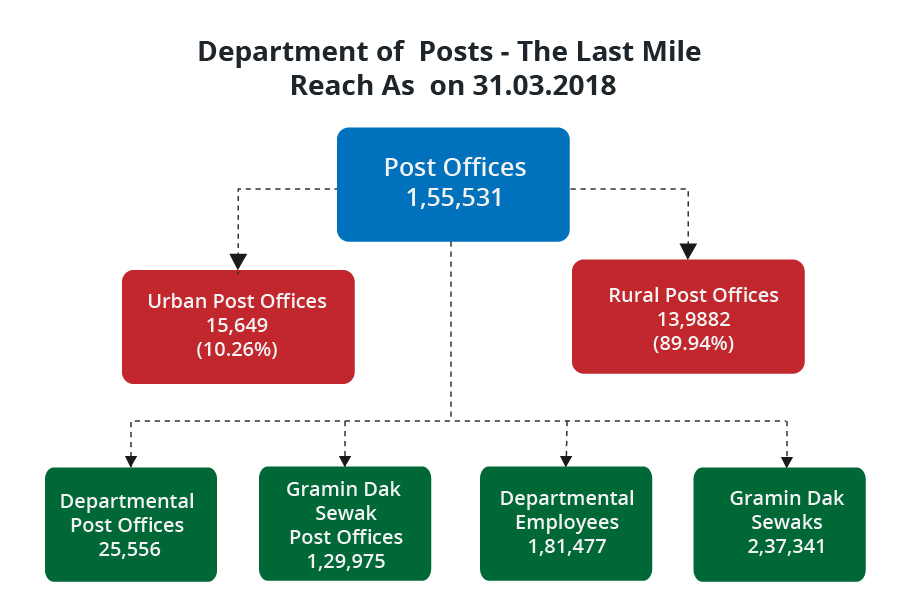

The Departments of Posts (now India Post), with a wide network of nearly 155,000 branches, employed about 4.2 lakh people, both departmental staff and mail delivery persons in rural areas (Grameen Dak Sevaks). As many as 90% of the post offices are now located in rural areas and it continues to be the backbone of communications for rural India until recently.

In the early 2000s, reforms were envisioned for the postal department but it came into reality during 2005-2007. The government laid out a plan to computerise about 80,000 branches (half the network).

Besides, a number of business products like speed post, express parcel post and business posts were introduced. It also brought in value additions like collection from customer premises, credit facility and volume-based discounts among others.

In 2007, the government told the Lok Sabha that the workload of postal workers did not reduce due to the installation of telephones in villages and private courier services as the department had branched out to deliver varied services. The government also said it had no plans to privatise the functioning of the department.

In 2010, an inter-ministerial committee on financial inclusion recommended structural changes to create a wider technological platform, a move that would take its low-cost banking services to the rural unbanked population.

The postal staff were also engaged in select villages to collect market data for the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Defying norms

Purnima SG, a postwoman in a male-dominated industry (82% of the staff are men) who took up the job after her husband’s death while in service, says the department gave training to them time and again when additional services were brought in.

Purnima, a two-time winner of the best mail delivery person in the department, helps her customers open saving accounts, transfer money and with mobile banking facilities.

Although she did adapt to the technology changes at work, she hasn’t used an e-mail service till date. While she felt no need for it, the lack of computer skills (from logging the data at the sorting stage to delivery) kept her away from it. But she uses a POS machine to get e-signatures when she delivers posts.

And post-2015, the boom in e-commerce and the surge in number of cash-on-delivery consignments led India Post to partner with major e-commerce portals for delivering pre-paid goods.

Information Technology and Communications Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad had projected that revenue of India Post from such deliveries would go up to ₹1,500 crore. But even in 2019, the revenue from such services did not cross ₹350 crore.

Financial position of India Post

While the use of postcards and letters fell rapidly, the cost kept rising with each passing year. The average cost of a postcard (from printing to distribution) was ₹12.98 in 2017-18, the revenue from it was only 50 paise. The cost has risen from ₹12.15 in 2016-17 and ₹9.94 in 2015-16, according to the Department of Posts (DOP) annual report.

The annual deficit of the department kept increasing from ₹1,595.82 crore in 1999-2000 to ₹6,378 crore in 2014-15 and to ₹13,977 crore in the financial year 2018-19.

Of DOP’s expenses, salaries and pensions constituted more than 90% of the gross expenditure.

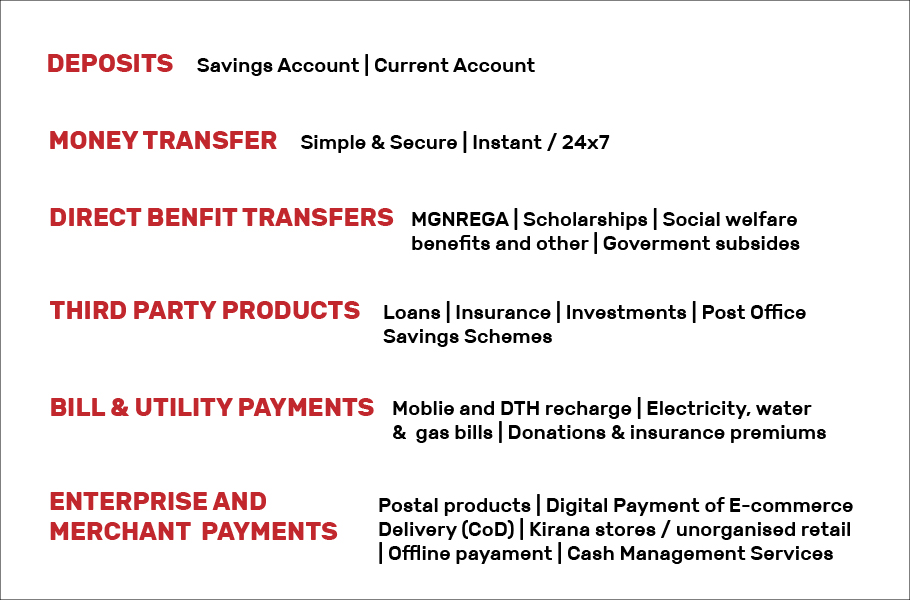

The government accorded approval for the setting up of India Post Payments Bank (IPPB) in 2016 with a total project outlay of ₹800 crores and rolled out 650 IPPB branches and 1.35 lakh access points across the country. Through IPPB, the government plans to introduce a host of services.

Today, in the wake of COVID-19 shutdown, the department delivers personal protection kits (to health workers) to medicines and essentials. But this is limited to only certain blocks in the country.

In Karnataka, the department tied up with the Karnataka State Mango Development and Marketing Corporation (KSMDMC) and started delivering mangoes to customers. The department delivers nearly 3,000 mango packs of 3 kg each daily.

However, Osama Manzar, founder-director of Digital Empowerment Foundation, says the department is still not fully equipped to go digital. While all of them were supposed to have internet connections, they are still non-functional in thousands of post offices, he says.

“The postal department could have gone digital long before. But they didn’t. With its wide network, ideally they should have become strong local delivery, supply and procurement centres,” he says.

Manzar believes that integrating all the post offices in the country through e-networks could have worked wonders for the department and to the citizens.

“In times of crisis like these, they could have delivered humanitarian aids on a much bigger scale,” he says.

At a time, Manzar adds, when people do not even have money to recharge their mobile phones, post offices could have become local internet service providers and acted like moving ATMs.

Coming back to Rattinamangalam, years after Margan’s death, the house from which the post office was operating was demolished. The new post office in the village, with a little bigger space, still awaits an internet connection.