- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

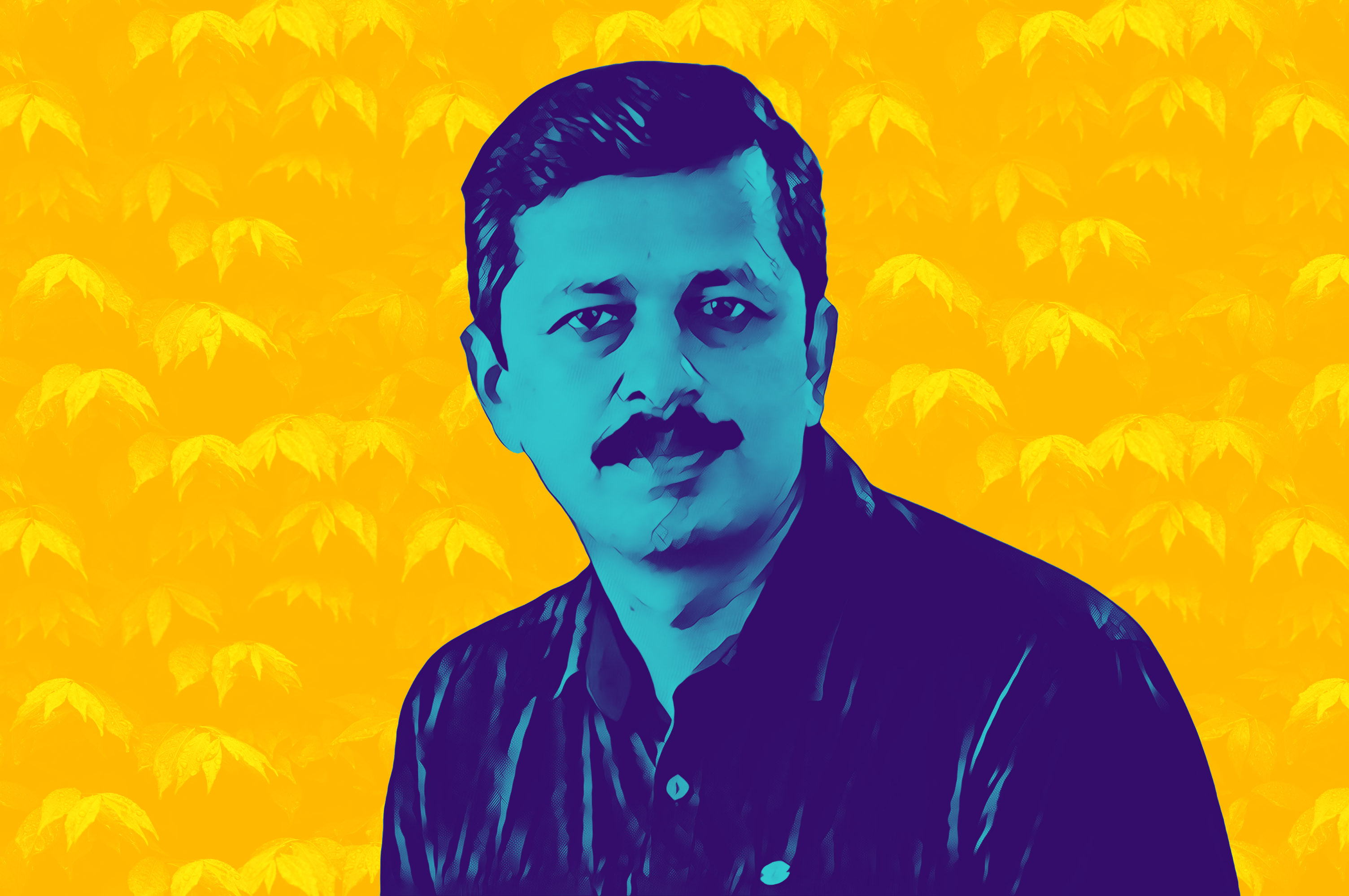

From Kuttanad’s belly, Jallikattu writer Hareesh takes the bull by the horns

Until six months ago, I used to go on these walks with a friend of mine. One day, he had asked: ‘Why do you think young women bathe, make themselves pretty, and go to the temple?’ ‘To worship’, I had answered. ‘No. Look again, carefully. Why wear their best clothes and get decked up if it’s only to worship? They’re subconsciously giving the signal that they are available...

Until six months ago, I used to go on these walks with a friend of mine. One day, he had asked: ‘Why do you think young women bathe, make themselves pretty, and go to the temple?’

‘To worship’, I had answered.

‘No. Look again, carefully. Why wear their best clothes and get decked up if it’s only to worship? They’re subconsciously giving the signal that they are available for mating.’

‘Don’t talk nonsense,’ I had laughed.

‘If that’s not the case, why do they avoid going to the temple for four or five days each month? They’re letting everyone know that they are unavailable at that time. Especially the priests. As you know, they’ve traditionally been the experts in these things.’

Hindutva groups were enraged when the above verses came out in the Malayalam magazine Mathrubhumi in 2018. Raising a strong banner of opposition, they demanded a stop to the column, a serialised version of a novel Meesha, written by debutant Malayalam writer S Hareesh, following which it was stopped.

For the writer, it was a complete surprise. “I never thought it would create such a tension. While writing, I had expected that this novel would be discussed largely in Dalit circles, since it is centred around a Dalit character,” he says, adding that when he got threats, Dalit intellectuals stood by him.

The novel was translated into English as Moustache by Jayasree Kalathil and it recently fetched JCB Prize for Literature Award.

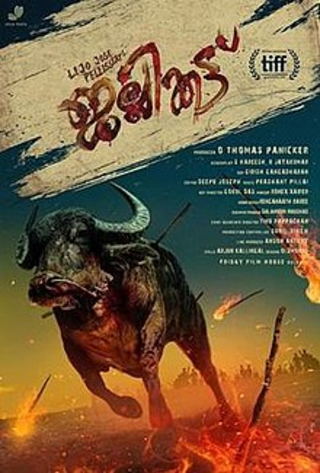

Now well known for his writing that wades into controversial subjects, Hareesh has another reason to celebrate. The Malayalam film Jallikattu directed by Lijo Jose Pellissery based on Hareesh’s short story, Maoist, has been selected as India’s official entry for the Academy Awards or Oscars. Hareesh had written the screenplay for the film.

“There are differences between the short story and the screenplay. The buffalo which runs amok from the butcher’s place is just one part of my short story. Actually, the story has one buffalo and one cow. But the film is basically a director’s media. So some changes were made in the story while writing the screenplay. The credit for the film’s success should also go to Lijo,” Hareesh concedes.

The success of the film and Hareesh’s stories have encouraged them to work on another film, Churuli, directed by Lijo.

For Haressh, films have become an extension of his writing career. In 2018, three of his short stories from the collection Adam were made into an anthology film Aedan directed by Sanju Surendran.

Hareesh, who is working in the revenue department, has so far published three collections of short stories besides this novel. He has also translated Randy Pausch’s The Last Lecture. The complete set of English translations of his short stories is expected in 2021.

Meesha faithful to Kuttanad

But Meesha remains his trademark work. The story is about Vavachan, a Pulayan (one of the Dalit communities in Kerala), who grows his moustache in defying the cultural norms of that time in Kerala — that Dalits should not have a moustache.

There are two parallel plots running in the novel. One happens in ancient Kerala where the state is the three regions called Malabar, Kochi and Thiruvithamkur. In the second plot, an unpublished writer tells the past stories to his school-going son.

Vavachan, when young, gets an opportunity to act in a play as a policeman. The role needs Vavachan to have a full-grown moustache. Despite being a cameo sans dialogues, he hogs the limelight for two reasons — one, a Dalit was acting as a policeman and two, a Dalit wearing a moustache that frightened the audience.

Even after the play is over, Vavachan continues to wear the moustache. The upper caste people take this defiance as an insult to them and want him caught and his moustache, which keeps growing supernaturally, shaven.

But Vavachan escapes from them and hides in the forest and is demonised. He is called the ‘Meesha’. As the World Famous Nose, a short story by acclaimed Malayalam writer Vaikkom Mohammed Basheer, Vavachan became the ‘world famous moustache’.

As the story of Vavachan unfolds, the author also describes the environmental and cultural history of Kuttanad, a delta region known for below-sea level farming done by people collectively. Hareesh also investigates the caste and gender inequalities, farming practices, the development of allopathy medicine in the first half of the 20th century.

Meesha, in one way, is an attempt at magical realism. Although being an avid reader of world literature, Hareesh says that he got the inspiration from Indian folklore for this work.

“Every work we read inspires us in some way. I do read (Colombian novelist Gabriel Garcia) Marquez and (Peruvian writer) Mario Vargas Llosa. But the stories we find in south Indian folklore are extraordinary. There are a lot of stories we need to explore. I am inspired by one such folklore that exists in Chengannur,” he says.

However, the spark to create Vavachan came from a neighbour, he revealls. “I always dreamed of writing a novel and wanted recording the Kuttanad landscape. Some of the traits and incidents found in Vavachan and his life were taken from my neighbour,” he admits.

The extra-curricular activity

Hailing from Neendoor in Kottayam district, the 45-year-old writer came into the literary world because of his voracious reading. While doing his SSLC (Class 10), one of his teachers playfully noted that his extra-curricular activity would be ‘writing stories and winning prizes’.

“I never wrote a story then. However, that has become true now,” laughs Hareesh.

“Although I have been reading literary works from a young age, my first writing attempt happened after college. After graduation I was jobless for some time. I was 22 then and at that time Mathrubhumi conducted a short story competition. I sent a story and surprisingly it got a prize,” he recalls.

But why do we read? While many writers have tried to come up with their own answers, Hareesh, through one of his characters in Meesha, says it is to enjoy a good story.

“There is nothing else beyond that. Why did we read Poombatta or Ambiliyammavan as children, or listen to our grandmothers’ stories? Just for the enjoyment of a good story. Children’s stories usually ended with a moral, but that was only to deceive parents into thinking that stories were edifying. It is the same yearning that leads one to Panchatantram or to a novel by Pottekkad — the yearning for a good story. The idea that reading provides us with a compass for politics, philosophy, spirituality, or insight into life and all that was pure nonsense,” says the character.

He goes on to ask how many stories do we know that we can narrate to children in a way that captures their interest?

“Fifteen? Twenty? Thirty, at the most? We could keep them interested for a few days with stories from Ramayanam and Mahabharatam, but all those power struggles, pageantry and piety are for grown-ups really, not children. Besides, they have so little relevance to today’s life. The great and the good in those stories are so backward compared to today’s children,” he writes.

And, the character continues, “a good story is like an arrow from the Pandava prince Arjunan’s quiver: a single arrow that becomes ten when released from the bow, and hundreds of thousands when striking the target.”

The statement is true with Meesha. The story that starts with the aim of telling a story of Vavachan, has become a socio, political, cultural and environmental history of Kerala.

Making a political statement through novels?

At a time when we hear news of state governments in Kerala and Karnataka opening salons for Dalits because they are denied haircuts, the incident in Meesha, wherein Vavachan is denied a haircut by an upper caste barber Govindan, a member of Velakkithala Nairs, is interesting to note.

“We only serve the Nairs and the castes higher than them. If you want, there are Vaathi barbers in Athirampuzha. They cut Pulayans’ hair,” says Govindan. Such instances of casteist discrimination have been recorded throughout the novel.

“I did not set out to write a novel about caste politics, but the journeys I took to research this novel and the process of writing it have brought about deep changes in my own outlook and understanding. It was in preparing to write this novel that I learned how to listen intensely to Dalit history, their knowledge about their own history, and consequently to the history of caste politics in Kuttanad,” writes Hareesh in the preface.

In the beginning of Jallikattu, the importance of buffalo meat to the locals is shown emphatically, with people thronging the only butcher’s shop every morning, and even before going to church on Sunday. The number of meat packets hung on a tree outside the church .

Similar scenarios can be found in the novel too, where the greed of the character towards meat is described in a salivary way.

“Apart from rice and fish curry, Pothan Mappila’s other culinary passion was buffalo meat. Even as he stood watch on the field edges, Mappila’s eyes would be on the buffalo tied to the plough, his mouth salivating at the thought of the tender meat between its forelegs, just below the spine. As he passed the muddy pools of water where the buffaloes wallowed, he smelled the fragrance of gently simmering beef. If there was a buffalo slaughter in the neighbourhood, he would lend a hand, and afterwards, he would bring his share of the meat wrapped in a banana leaf, and hand it over to his wife to wash and cut into pieces which he would carefully count. He would get rid of his son by sending him on a visit to his sister’s marital home. And as the meat cooked, flavoured with ground coriander, cumin and fennel seeds, he would sit right beside the pot, tending the fire and sampling it as soon as the meat began to release its juices. The son, back from the enforced visit, would be given the cooking pot to lick,” writes Hareesh.

At a time when the right wing is all gaga over ‘cow politics’ and one’s food choices, is Hareesh trying to make a political statement by writing about meat?

“We should have the freedom of choosing and doing the things we like either it can be food or writing. That is as simple it is,” he says.