- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How a network of small libraries is making room for more than just reading

Tucked away in a labyrinth of narrow streets crammed with buildings not far from the sprawling Madiwala lake in Bangalore is a tiny front yard where about a dozen children have gathered for some afternoon activity. They take turns to disappear behind a door, slip on a red clown nose attached by a string and then come back to face the others—a little game whose objective is to get over...

Tucked away in a labyrinth of narrow streets crammed with buildings not far from the sprawling Madiwala lake in Bangalore is a tiny front yard where about a dozen children have gathered for some afternoon activity. They take turns to disappear behind a door, slip on a red clown nose attached by a string and then come back to face the others—a little game whose objective is to get over the shyness of standing before a gathering by slowly looking at each person in the eyes. There’s a lot of clapping and laughing. Clearly, it’s fun and these children—all members of the Haadibadi community library—are enjoying themselves.

It will probably be the last weekend activity before the kids get busy with their annual school exams, says Geetha M, co-founder of Haadibadi (pronounced Haa-dhi-ba-dhi and meaning ‘by the wayside’ in Kannada), a collective engaged in streetplays and theatre. But the library will still be open to them.

“If somebody wants to come, sit and read or needs help with homework or preparing for their exams, we’ll be there,” she says. The regulars are mostly children from the neighbouring streets who go to local primary schools but most of whom hadn’t used a library before. “The idea is to introduce them to the concept of a library and access books so that maybe slowly they would explore libraries beyond,” says her partner Ravikiran Rajendran, 32, who grew up in this locality called Roopena Agrahara.

Two decades ago, it was an open neighbourhood with tamarind trees and grounds to play but now residential buildings have come up cheek by jowl, given there is an industrial area adjoining it. So children, especially girls, don’t have many outlets for play or other activities, he explains. “Now, space has shrunk, which is why we have more girls coming in than boys,” says Rajendran. At the library, there are read-aloud sessions to get the children started, periodic workshops and even video and movie screenings. “That kind of welcoming space for those who come from families where nobody else in the house is reading is also important,” says Geetha.

The Haadibadi library with its 150 members is fairly young—it was started in 2019 by crowdsourcing picture books, fiction mostly in Kannada and textbooks. Similarly, there are various fledgling libraries across the country and many of these are banding together under a collective called the Free Libraries Network (FLN)–each of them with their own story and goals but the common thread being that these are libraries that don’t charge their readers and whose focus is on teaching and learning.

FLN grew out of the Delhi-based non-profit, The Community Library Project (TCLP), which runs three libraries in the national capital, the earliest of which opened in 2014. “So the idea of FLN was always there with us but we were really striving hard to bring stability to our own library,” says Purnima Rao, a library activist who is part of the leadership team at TCLP and director at FLN.

“Actually, what happened in the pandemic was that we really discovered a whole other dimension of how libraries matter in a community. So that’s when many practitioners from across the country whom we had been speaking to anyway, suddenly woke up to the fact that we need to think of it like a people’s movement,” she says. “And so we just started meeting online, we did trainings and webinars. And more and more people joined the conversation.”

Currently, FLN has nearly 100 members—90 per cent of them are small libraries run by various organisations and the remaining members are either individual librarians or educators.

Far away from Bangalore, in the Jorhat district of upper Assam, Rituparna Neog is also one of those who started a community library recently, beginning with a personal collection of books. Later, more books were donated by friends and well-wishers, some of whom he has never met except through social media.

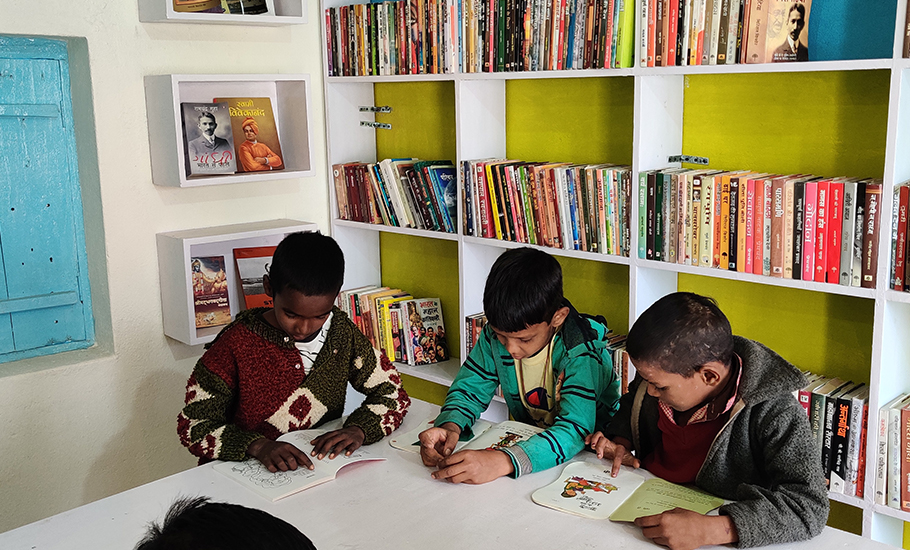

“Right now we have more than a thousand books in the library in Assamese, English and Hindi,” says Rituparna, 28, who is a member of FLN. The venture is called Project Kitape Katha Koi which translates to ‘books talk to you’. Currently, more than 50 children from Rituparna’s village of Ahatguri and its vicinity, which includes a tea garden, regularly visit the library. Their parents have never been to college except for a couple of mothers who dropped out in their first year as undergraduates–one of them is currently the librarian. “The parents were really excited because they also felt there is this gap. They really value education,” says Rituparna, recounting his own connection with books and libraries.

As a youngster, Rituparna’s parents encouraged reading and saving up money in a piggy bank–every year, this would be used to buy books. Rituparna, vividly recollects how his mother first introduced him to the world of reading by buying two children’s magazines during a visit to Jorhat town for a festival years ago. “My mother never could go to college but she knew the value of education,” says Rituparna. “The library really was a saviour for me at one point of time when I was growing up. I’m a transgender person, so I used to get bullied….the library was the safest place for me. It became a very integral part of my journey so I always wanted to do something around libraries.” At Project Kitape Katha Koi, the children do a lot of reading aloud and they get to hear stories, says Rituparna.

Purnima Rao puts this into perspective. Public libraries in India are mostly catering to those who are already readers but the model of transforming people into readers has been missing from public discourse, she points out. Reading aloud, she says, is the crux of everything community libraries like TCLP do. “If we don’t do that, we are just a room with books,” she says. “When you see children huddled around one book and taking turns to read it and talking about it with each other, it is a radically powerful definition of reading. And, it’s not just children.”

Jatin Lalit, who runs the Bansa Community Library and Resource Centre in Uttar Pradesh’s Hardoi district, comes up with an example of how an elderly resident in his village was the first to drop in even before they had formally opened in November 2020.

“Before that, he used to read the same newspaper thrice a day. He was the first to borrow a book and till date, he takes five books every week,” says Lalit. The objective of starting a free community library, he says, was to help students preparing for competitive exams for government jobs. Typically, they would move to cities like Lucknow or Kanpur to prepare for the exams. “We have 1,700 members from 36 different villages who have been to our library so far,” says Lalit.

The FLN initiative helps independent libraries like his to access books by reaching out to publishers, he says.

“We do a lot of advocacy with governments, publishers, writers and illustrators,” says Rao, who points out that community libraries have largely been an unorganised segment. “People have been doing this kind of work in isolated silos for many, many years. So obviously when someone jumps into it as a practitioner, they are functioning on their own and there is this extreme loneliness that comes from doing this work.” The network therefore helps to connect them so that they can pool ideas and learnings.

As Lalit notes, many of these community libraries are looking to evolve a sustainable model and eventually act as a bridge to the existing public library network. Lalit graduated from law college a year ago and is currently practising in Delhi—the Bansa community library he set up in his hometown is managed by a staff of three, he says. It’s a similar story with both the Haadibadi Community Library and Project Kitape Katha Koi—Geetha is a research fellow in a teacher education programme while Rituparna Neog works full-time with an NGO in Guwahati, keeping in touch with the librarian weekly over a video call. “I really want to see more and more libraries and I want to see them inculcate critical thinking among children,” says Rituparna.