- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Flyovers: High-speed development or wasteful expenditure?

In 2008, the then Tamil Nadu CM M Karunanidhi recalled an incident that had happened when he used to live in Chennai’s Thyagaraya Nagar (T Nagar) decades ago. His son Stalin, then a young child, had swallowed a safety pin one day. The agonised parents — Karunanidhi and wife Dayalu Ammal — could not rush him to the doctor in nearby Kodambakkam as they had to wait at the railway gate...

In 2008, the then Tamil Nadu CM M Karunanidhi recalled an incident that had happened when he used to live in Chennai’s Thyagaraya Nagar (T Nagar) decades ago. His son Stalin, then a young child, had swallowed a safety pin one day. The agonised parents — Karunanidhi and wife Dayalu Ammal — could not rush him to the doctor in nearby Kodambakkam as they had to wait at the railway gate for half an hour. The pin was finally removed and their son survived.

Karunanidhi was speaking at the inauguration of the Usman Road flyover in T Nagar. The message of his story was not lost on his listeners — the importance of a flyover that would ease congestion and save commuters the pain of remaining stuck in traffic snarls. And the flyover was built in a record time of 10 months.

More than a decade later, T Nagar residents can still relate to Karunanidhi’s story and the pain of a safety pin. However, now it’s the Usman Road flyover itself that feels like a pin lodged in the throat of commuters — something they can neither gulp down nor throw up.

- Flyover nuggets

- Kemps Corner at Pedder Road, Mumbai is India’s first flyover bridge built at a cost of around ₹17 lakh in 1965.

- Anna flyover, built in 1973, was the first flyover in Chennai and the third in India.

- The Hebbal flyover in Bengaluru, built by Gammon, is India’s longest urban flyover, spanning 5.23 km.

- Kathipara flyover in Chennai is the largest cloverleaf flyover in Asia.

Every day, VS Jayaraman, a resident of Motilal Street in T Nagar, navigates through a line of hawkers, tightly parked vehicles, and bikes and autorisckshaws squeezing their way onto the narrow service road underneath the flyover, to move towards Usman Road, even though it is just a few yards. “Ever since the flyover came up, residents on the many adjoining lanes have been left with little option but to put up with the congestion and amplified traffic,” he says.

Before the flyover came up, vehicles found it difficult to navigate in the area. However, the construction of the flyover has changed nothing, he says. “The traffic congestion remains. In fact, now there are long traffic snarls that extend the travel time, even if you take the flyover. Crossing Usman Road has become impossible.”

From the time Chennai’s first flyover — Anna flyover — was thrown open in the 1970s to decongest the traffic between Mount Road (now Anna Salai) and Nungambakkam, the city has seen a spurt in the number of flyovers. This is true for cities across the country wherein governments view flyovers as a symbol of high-speed development and a way out of traffic congestion. As a result, there has been a steady rise in the number of flyovers over the years.

But are they really a solution to India’s traffic woes? The Federal explores the ailing and failing flyovers in three cities — Chennai, Hyderabad and Bengaluru — in an attempt to see why governments persist on building them even when modern infrastructure history shows they may not be serving the envisaged purpose.

Badly planned structures

A textbook example of another underutilised and badly placed flyover in Chennai is the GK Moopanar flyover near Cenotaph Road that links the road to Kotturpuram. Residents in the area find it difficult to figure out the actual purpose of the bridge. “Vehicular movement on the bridge is negligible and the junction is not a major one. The two main roads, perpendicular to each other, have little traffic. It gets bad only in the morning and evening. And the flyover has done little to solve the issue,” says Krishnamurthy, a resident of Nandanam.

The Perambur and Murasoli Maran flyovers are two other examples of underutilised flyovers in the city. These two are used most often in monsoon, when rains leave the lower ground waterlogged.

More than 600 km away from Chennai, the residents of Hyderabad too have something similar to say about flyovers dotting the cityscape. A major IT hub, Hyderabad currently has 33 flyovers and another 15 under various stages of construction. Every monsoon, the city becomes a nightmare for commuters. A short shower is enough to leave some of the flyovers heavily waterlogged. Shoddy work by contractors and municipal corporation engineers forces commuters to wade through waterlogged roads, adding to the congestion.

At least five flyovers, located in the high traffic zones, face water-logging problems during monsoon. In addition to the inconvenience caused to commuters, the stagnant water can cause structural damage to the flyovers, warns SP Anchuri, vice-president (south) of the World Congress of Structural Engineers.

A city (in)famous for its traffic, Bengaluru’s city administration has sanctioned several flyover and underpass projects with poor and faulty designs over the years, adding to traffic woes. For instance, unlike the well-planned Domlur bridge or the Hebbal flyover, the Richmond Circle flyover, National College flyover, Tagore Circle underpass, Krishnarajapuram hanging bridge, and Maruthi Sevanagar over-bridge are some of the urban structures that are either redundant or fail to ease present-day traffic.

The Richmond Circle flyover acquired a cult status after a Kannada movie director shot a successful film based on its faulty design. It was one of those early bridges in the city that was so poorly designed that a traffic cop had to man the traffic and the flyover had signal on top. Initially, it was meant for one-way traffic. The flow of traffic was reversed later and subsequently it ended up as a two-way lane.

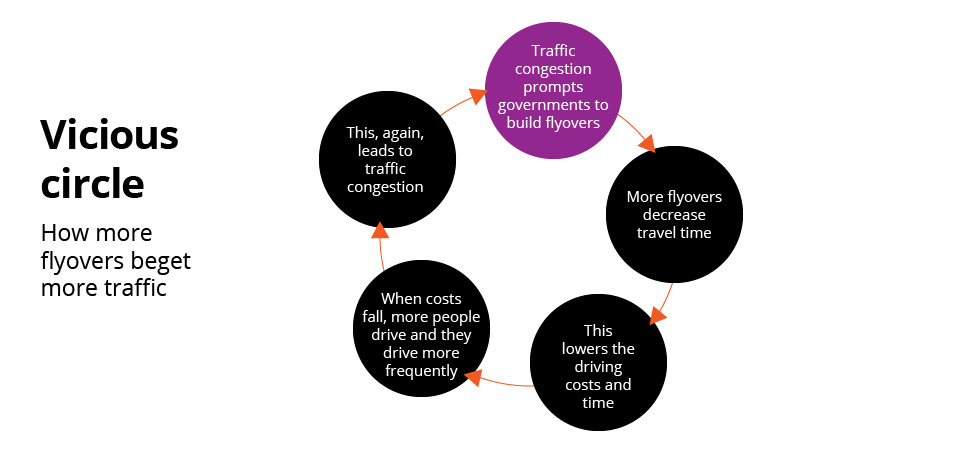

Aswathy Dilip, senior programme manager at the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP), Chennai, says, “Flyovers are seen as effective remedies for solving traffic issues. That is not the case because even if they do offer solutions, the problem crops up after a few years. In fact, world over the focus is on bringing down the structures, and looking at better ways of utilising public spaces and improving movement on them through better transportation.”

Damaging the environment

Indiscriminate construction of flyovers only creates more vehicular traffic and damages the environment, says public transport expert Dr C Ramachandraiah. “The spurt in the number of flyovers is unnecessary. These projects are contractor-driven and car-focussed. The increase in flyovers compromises the public transport system, which in turn damages the environment,” he explains.

Aswathy of ITDP adds that in a bid to facilitate the movement of private vehicles like cars, which constitute less than 10 per cent of the total vehicle population, the larger share of public transport is ignored. The latter doesn’t benefit from flyovers or expressways.

The state roadways buses hardly use flyovers since they have to pick up passengers on the way. “The government does not have an urban transport policy. The people, and not the vehicles, must be the focus of the policy,” the expert says. Flyovers, essentially, cater to a small section of society at the expense of everyone else.

In the case of Bengaluru’s National College flyover and Tagore circle underpass, not only did the civic body overestimate the vehicular movement, it also failed to have public consultation before constructing the bridge. The civic body estimated the traffic to be about 10,000 car passenger units per hour, while in reality the volume did not go up as projected; it was just a third of what was estimated.

“The government wastes precious public money on bridges and flyovers, which, for today’s traffic, are redundant. That shows the civic body and contractors failed in their job and do not foresee what is coming,” civic activist Srinivas Alavilli says. “They could have spent the money for better purposes like improving the public transport system and encouraging less vehicles on roads,” he adds.

Leading environmental activist Capt J Rama Rao says that flyovers can, at best, offer a temporary solution. “The government’s focus should be on how to reduce vehicular traffic and encourage public transport. Flyovers will only add to the mess.”

“Flyovers are only a stop-gap arrangement. At the most, they can resolve an immediate crisis for a while but can’t serve as a long-term solution to traffic snarls,” says Anant Mariganti, president of Hyderabad Urban Labs.

Aswathy explains that if the focus is solely on decongesting traffic, then mass transit is better than flyovers. “In Chennai, where there are 1 crore people, we would ideally need 400 km of mass transit (40 km of mass transit for every 10 lakh population). At the moment, we have achieved just about 150 km of mass transit (Metro rail and suburban railways).” While a giant flyover can cost several hundred crores, a mass rapid system can be developed at a fraction of the cost and is more effective, she adds.

Citizen protests

Several citizens’ groups and environmental activists are up in arms against the Telangana government’s ambitious Strategic Road Development Plan (SRDP) envisaging the construction of multi-layer flyovers at 20 key junctions in the city.

One of the flyovers would require trees to be axed at KBR National Park, the city’s largest lung space. Dismissing the concerns of the environmentalists as ‘unfounded’, a senior Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation official says, “There will be no threat to KBR Park or the environment on account of the SRDP. In fact, pollution levels will come down after these flyovers are built due to lower carbon emissions.”

The citizens’ movement in Bengaluru sees more success when it comes to stalling unnecessary and unscientific projects. One such is the recent ₹1,800-crore, seven-km steel flyover project that the state government scrapped after widespread protests and petitions. The project, if approved, would have resulted in the cutting of 3,800 tree in the already choking city.

Even the Krishnarajapuram suspension bridge on Old Madras Road, inaugurated by the late prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in 2003, and adjudged as the Outstanding National Bridge in 2009 by the Indian Institution of Bridge Engineers, failed to ease Bengaluru’s road block. Why, in that case, do we continue to build these giant monstrosities instead of developing the public transport system?