- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

FarmVille comes alive: Contract farming a boon to farmers

When tech giant Facebook was getting popular over a decade ago, the online virtual farming game FarmVille kept internet users across the world hooked to the social networking platform. The game allowed users own a piece of virtual land and cultivate crops. Millions of Facebook users logged on to the platform to sow seeds and water their crops daily. The game was so popular that its...

When tech giant Facebook was getting popular over a decade ago, the online virtual farming game FarmVille kept internet users across the world hooked to the social networking platform. The game allowed users own a piece of virtual land and cultivate crops. Millions of Facebook users logged on to the platform to sow seeds and water their crops daily.

The game was so popular that its developer, Zynga, contributed to 12 per cent of Facebook’s overall revenue in 2011. During FarmVille’s two-year reign, the social media giant’s userbase grew from 200 million in April 2009 to 750 million in July 2011. However, FarmVille remained just another game in the market.

Come 2019, the trend has caught up to places like Bengaluru, Coimbatore, Hyderabad and Surat, except this time the farming is for real.

Every alternative weekend, Chandra Prakash Agarwal, a chartered accountant working in Bengaluru, travels to the outskirts of the city to harvest and collect vegetables from the 600-sq ft farmland that he has rented from a farmer in Janthagondahalli.

Last weekend, he carried home a bag full of tomatoes, spinach, sponge gourd and bottle gourd, among other vegetables — all organic — from his farm managed by Narayan Reddy. “Rather than going to the local store and picking up market-driven, pesticide-laced vegetables, I get chemical-free food products that I choose to grow,” Agarwal says. “It is good to know where your food comes from and how it is grown.”

Not many people have the luxury of owning terrace gardens in the city where they can grow vegetables. As for those who do, lack of time and farming experience are constraints. Yet, many dream of spending time on a farm and eating their own produce.

There are at least 1,500 people in Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Surat who rented out farmland in the cities’ outskirts with the help of an agri-tech start-up, Farmizen. Started in 2017 by Shameek Chakravarty and his co-founders Sudaakeran Balasubramanian and Gitanjali Rajamani, Farmizen acts as a tech enabler connecting farmers with consumers instead of playing a traditional intermediary role of connecting farmers with wholesalers and retailers.

It provides a platform where people in Tier I and Tier II cities can rent a piece of land and grow a variety of organic vegetables of their choice. For now, the company gets a majority of its customers from Bengaluru.

With the dwindling green cover and vanishing water bodies in and around Bengaluru, the soil degradation led to lesser nutrients in the vegetables coming into the market. Worried by this, more environment-conscious people wanted access to organic food produce though it is expensive.

How the model works

According to a 2018 report by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), about 76 per cent of Indian farmers want to do something other than farming. Increasing mobile penetration and internet access in rural areas are changing this perception. Many start-ups have tapped into the potential of the rural market and are trying to address the gaps in the agriculture sector. Besides helping farmers with weather, water and soil management services, the firms try to address the gaps that exist in the agri-retail supply chain by providing farmers with direct market access.

In the case of Farmizen, consumers can rent out 600 sq ft of farm land for ₹2,500 a month and decide what vegetables they want from their farm. Vegetables grown in the plot are enough for a family of four. Besides what’s grown in their land, customers can opt to buy produce from a common area of the farm.

The farmland are owned and managed by the farmer and Farmizen helps channelise demand and supply, and in the distribution process through tech help. Farmizen ties up with farmers who have more than 1.5 acres of land (roughly serving about 80-100 customers per farmer). The land maintenance, water, electricity and labour are borne by the farmer. Farmizen focuses on non-core tasks, such as supplying seeds, managing the technology, getting customers, logistics, and advertising.

“We do not want consumers to just buy organic food. We want them to engage in the harvesting, packaging, and distribution process. Most of our farms are 20-30 km from the city so that people can visit them and understand the process,” Chakravarthy, founder and CEO of Farmizen, says.

The company believes in an asset-light business model and does not spend money on buying land. Instead, it invests in tech and partners with farmers. It’s a win-win situation for all — consumers, farmers, and intermediaries like Farmizen.

In recent years, a handful of start-ups have made agriculture a lucrative option for farmers. Start-ups like FreshWorld, NinjaCart, BigBasket, and Crofarm are in a contract with farmers to sell produce to customers either through online or offline channels. With Farmizen, the customer gets to grow what they want.

Chakravarty believes consumer engagement with food production and processing will make the food supply system more meaningful. The company targets a niche audience, and customers like Agarwal do not mind paying ₹2,500 a month.

“I anyway spent ₹1200-1,500 a month on vegetables. If I bought organic produce, I may have spent ₹2,000-2,200 a month. But there’s a cost advantage to owning a plot at ₹2,500 and knowing what and how the food comes to my plate,” Agarwal says.

Chakravarty says the demand from Tier-II cities is growing and the cost of the land could get lower as the cost of logistics may cut down expenses.

A tech-enabled farmer

Accessing a smartphone and managing the farm profitably were things Reddy hadn’t imagined until a couple of years ago. While Reddy works in the farm all through the week along with seven other labourers, he gets busy managing weekly orders from customers between 7-9 am on weekends. He ends up chatting with customers who visit their plot.

Reddy swipes through the app with ease to look at customers’ requirement and manages to harvest and clean produce, and keep it ready in bags to be sent to them.

Unlike many farmers, Reddy keeps an account of his finance and notes how many kilograms of produce he sends his customers. He wants to ensure that he sends 25 kg of produce per customer every month.

Reddy, who owns five and a half acres of land, used to do cattle farming for seven years until he switched to organic farming. He says every year at least two cattle would die and the loss (approximately ₹1-1.2 lakh) would offset the profits he made for the year. He believes in the benefits of organic farming now and say it enriches the soil and betters the health of consumers.

Today, with about 170 customers, Reddy says he earns a profit of ₹30,000 a month, per acre of land. “Initially, the company wanted to manage the land and give me monthly rental for it. That way I would have quit agriculture and just be a real estate owner. I didn’t want to do that so I partnered with the company to remain a farmer,” Reddy says with a smile on his face.

Market dynamics shake things up

With diverse climatic conditions, India ranked second in fruits and vegetables production in the world after China. As per the National Horticulture Board, during 2015-16, India produced 169.1 million metric tonnes of vegetables in 10.1 million hectares of land. The organic market was growing at a compounded annual growth rate of 25 per cent as compared to the global rate of 16 per cent.

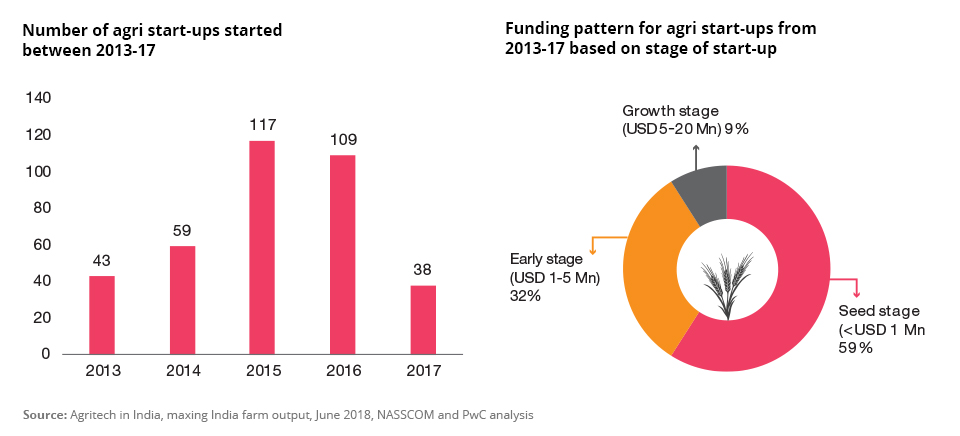

While the retail and e-commerce sectors took a large chunk of investors’ funds, agri start-ups have garnered reasonable support in recent years. Between 2013 and 2017, about 366 start-ups came up in India, according to industry body Nasscom.

That said, many have shut shop for a lack of funds and failing to understand market dynamics. For instance, Karthik Natarajan, a Bengaluru-based entrepreneur, founded Farmily with a similar business model like Farmizen. But the start-up is defunct as the founder struggled to raise funds for two years and investors were wary about investing in agri-tech start-ups.

Nagaraja Prakasam, an angel investor, says that while farmers in a developed country gets as much as 70 per cent of what consumers pay, in India they get about 30 per cent.

“Bengaluru consumes around 4,000 tonnes of fruits and vegetables. There are many traders/commission agents at mandis, who, without any education, make a few hundred crores. With agri start-ups raising funds, I hope they disrupt the system and take care of farmers,” he adds.

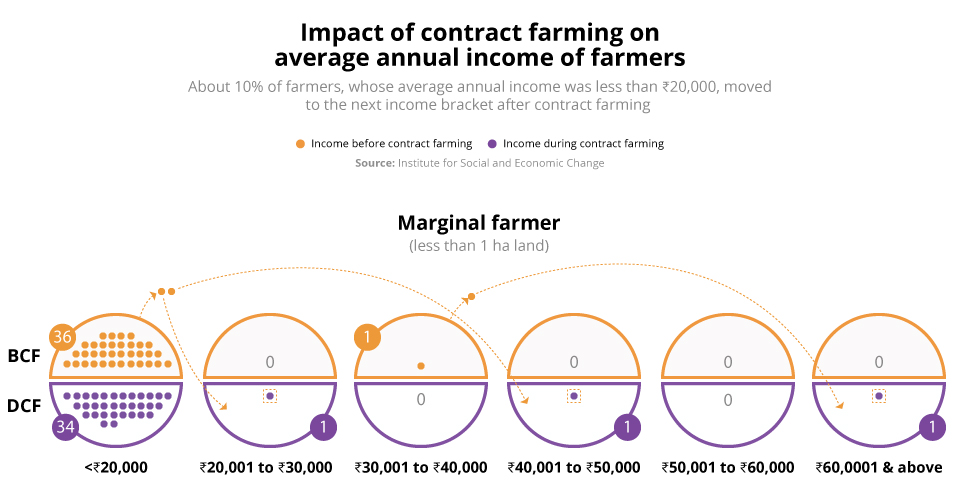

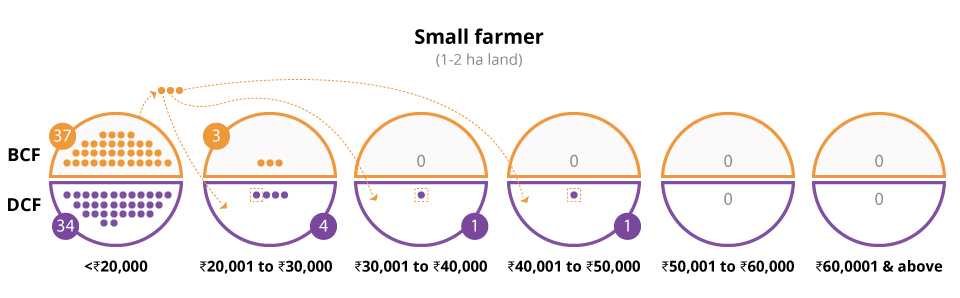

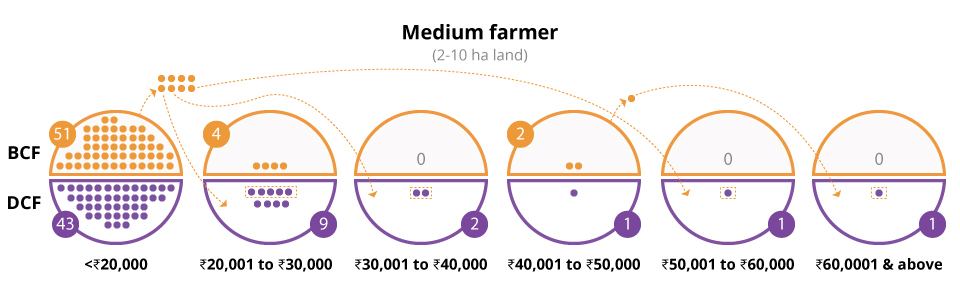

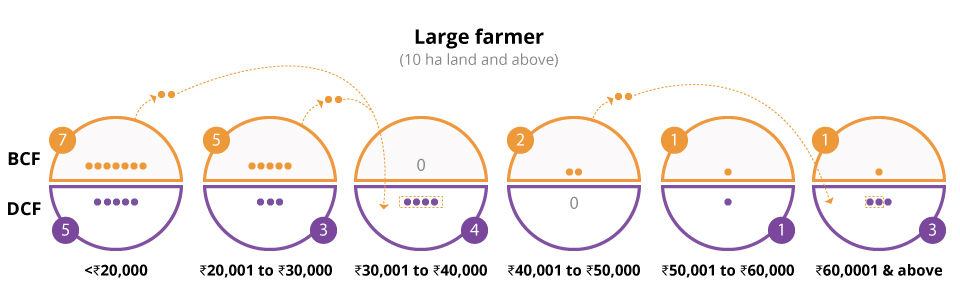

A report by the Institute for Social and Economic Change states that about 10 per cent of farmers, whose average annual income was less than ₹20,000, moved to the next income bracket after contract farming started. This is, hopefully, a sign of the much-needed change.