- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

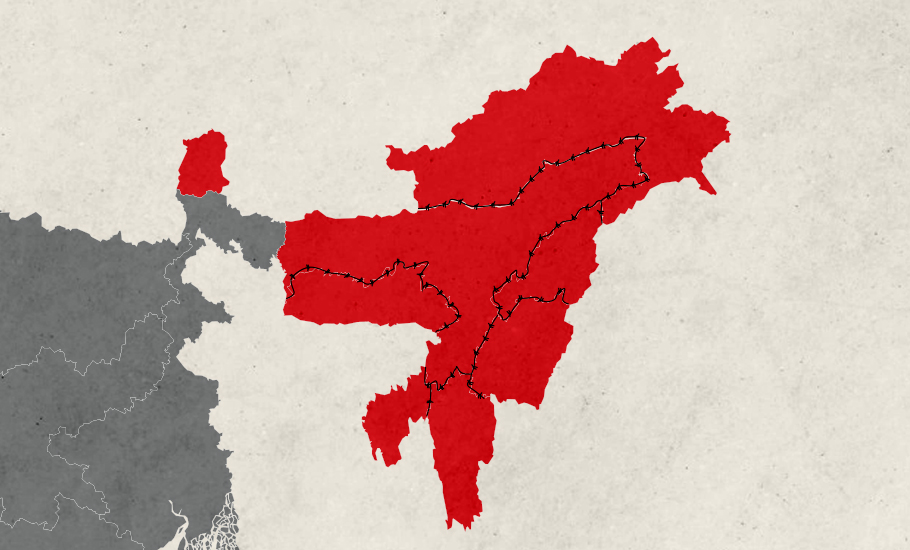

Explained: Why North-East states are at loggerheads over border

There are several such villages in the region where boundaries between states remain contested, often triggering inter-state conflicts akin to one witnessed recently between Assam and Mizoram, and Mizoram and Tripura, laying bare a major chink in India’s nationhood concept.

The ongoing border dispute between Assam and Mizoram led to massive violence, leading to the death of at least five Assam police personnel on July 26. More than 60 people were injured, and as per the latest reports, the situation on the border is volatile. So, the question is: Why are the two states in sparring mode? What are the issues? In fact, most North-East states are fighting over...

The ongoing border dispute between Assam and Mizoram led to massive violence, leading to the death of at least five Assam police personnel on July 26. More than 60 people were injured, and as per the latest reports, the situation on the border is volatile.

So, the question is: Why are the two states in sparring mode? What are the issues? In fact, most North-East states are fighting over boundary issues. Here, we are replugging our Eighth Column article, which first appeared in October 2020, an explainer, delving into the whole issue.

In case, you want to read the latest Eighth Column story, it’s here.

Here is the BIG story:

Ummat and Phuldungsei are sleepy tribal villages nestled in two remote corners of Northeast India. Some of the residents from both these villages, separated by more than 500 kilometres, enjoy a dubious advantage of voting and drawing rations from two states.

There are several such villages in the region as in many places boundaries between states remain contested, often triggering inter-state conflicts akin to one witnessed recently between Assam and Mizoram, and Mizoram and Tripura, laying bare a major chink in India’s nationhood concept.

“When we could resolve the boundary issue with Bangladesh, why can’t north-eastern states resolve their inter-state boundary disputes? We are not different countries. We are states of the same country,” Home Minister Amit Shah said at a meeting of the BJP-led North East Democratic Alliance (NEDA) in Guwahati in September last year.

Incidentally, all the ruling parties in the seven-sister states of Northeast are part of the NEDA, and Shah mistakenly assumed that the common political identity would obliterate the much deeper ethno-nationalistic and territorial aspirations of myriad ethnic groups that are in the root of these conflicts.

The state of affairs

When India attained freedom, the present states of Nagaland (barring Tuensang division which was part of the NEFA), Meghalaya and Mizoram were districts in Assam. While the state of Meghalaya was carved out of the districts of Khasi, Garo and Jaintia hills in Assam, Mizoram was Lushai Hills.

Arunachal Pradesh, comprising several frontier divisions, including Tuensang, was part of the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) administered by the governor of Assam.

Manipur and Tripura were independent princely kingdoms that merged with India only in 1949 to become ‘Part C States’, equivalent to present-day Union Territories.

At the time of reorganising Indian states and territories along linguistic lines by enacting the States Reorganisation Act, 1956, the Northeast remained untouched, undermining aspirations of ethnic communities, some of whom like the Nagas were waging armed rebellion for a sovereign independent state.

As the separatist movements started spreading from Naga hills to other parts of the region, the process of gradual administrative reorganisation of the region started with the formation of new states.

Nagaland was granted statehood in 1963 and Meghalaya in 1972. In the same year, Manipur and Tripura were elevated to full-fledged states. Mizoram too was carved out of Assam to become a Union Territory in 1972, and subsequently it became a full-fledged state in 1986. Arunachal became a state in 1987, last among the seven sisters.

The idea behind the restructuring is to reduce conflicts by accommodating territorial aspirations of ethnic communities such as Nagas, Mizos, Khasis, Manipuris, Garos, Arunachalis and others.

The delineation of the state boundaries however failed to strictly conform to the ethnic specificity and also did not take into consideration the pre-independent era “historic boundaries” demarcated along ethnic lines, leading to many festering inter-state border disputes.

Assam, out of which most of the present north-eastern states have been created, insists on adhering to boundaries marked after Independence. But many other states such as Nagaland and Meghalaya harped on “historic boundaries” as its territorial jurisdiction.

Many in Nagaland did not accept the state’s boundary defined in the Nagaland State Act of 1962, insisting that it should include all areas which were part of Naga territory according to an 1866 notification.

As Nagaland did not accept its notified borders, the first border flare-up between the two states occurred at Kakodonga Reserve Forest in 1965, barely two years after Nagaland attained statehood. Since then there have been several clashes as both the states accused each other of illegally occupying territories.

Border disputes

The bloodiest border clash in the history of the region took place at Merapani in Assam’s Golaghat district in June 1985, when forces of the two states fought a fierce gun battle for about four hours, leaving 41 dead, including 28 Assam Police personnel.

Assam and Nagaland share a 434-km boundary. Assam claims Nagaland has been encroaching upon over 66,000 hectares of land belonging to the state. Nagas, on the other hand, lay claims over it, citing that the areas were transferred out of the Naga Hills after the British annexed Assam in 1826.

Similarly, Meghalaya lays its claim over 356 villages, including Ummat, in two blocks of Assam’s Karbi Anglong district saying they were part of the erstwhile United Khasi and Jaintia Hills created in 1835.

There are similar claims and counter-claims, which frequently snowball into border standoffs.

There were three major border conflicts in the region within the last one year, the latest being the standoff between Assam and Mizoram. The immediate trigger for the latest conflict was Assam’s objection to construction of a Covid-19 testing centre by the Mizoram government within its “own territory”.

Soon, the locals got involved and clashed with each other in which at least eight people were injured and a few huts and small shops were torched earlier this month.

Some Mizo organisations, however, tried to downplay the border conflict saying it was a fight against illegal Bangladeshi immigrants as the areas within Assam are dominated by Bengali-speaking people.

At the heart of the conflict is a border dispute with both Mizoram and Assam laying claims over Lailapur, the epicentre of the latest conflict.

Around the same time, Mizoram also got embroiled into a border tussle with another neighbouring state Tripura after the former imposed prohibitory orders under Section 144 on public movement at Phuldungsei, ostensibly to prevent attempts by a social organisation to build a Shiva temple there.

While the Tripura government claims that the village falls under North Tripura district, Mizoram claims the village falls within the jurisdiction of its Mamit district.

The village was also in the news in August this year when the Tripura government flagged that 130 residents of the village were included in the electoral rolls of both Tripura and Mizoram. These villagers also reportedly have ration cards of both the states.

Last year clashes erupted between Assam Police and the people of Umwali village in Meghalaya in which several people, including women, were injured.

Line of no control

Apart from Nagaland, Mizoram and Meghalaya, Assam also has a protracted border conflict with Arunachal Pradesh, severely affecting the relations between neighbouring states.

Several attempts have been made in vain to settle these disputes through bilateral negotiations between the states in the past. Third party interventions too have failed to break the stalemate until now. In 2005, the Supreme Court had instructed the Central government to constitute a boundary commission to settle various inter-state boundary problems in the region.

Constitutions of several such commissions failed to resolve the disputes as the contesting states did not accept their recommendations.

New Delhi has so far succeeded only in brokering temporary peace, as it did to calm the latest tension between Assam and Mizoram.

These long-pending disputes, apart from threatening India’s nationhood concept, are also severely impeding developments in the disputed areas, as had been pointed out recently by Arunachal Pradesh Chief Minister Pema Khandu.

Taking advantage of their contested status some villagers also try to exploit the situation possessing dual voters identity cards in order to claim benefits from two states.

Shah in September last year Shah called upon the chief ministers of the north-eastern states to settle the border disputes in a time-bound manner before 2022, when India will celebrate 75 years of its Independence.

However, given the complex and emotional nature of the disputes, meeting the deadline seems to be a stiff challenge.

“To solve such long-festering border issues, the Centre first needs to understand the ethnic aspirations of the different groups of people that altogether make the seven sisters. By simply lumping the contiguous states together as one common entity—Northeast—without understanding the historical grievances and then claiming them to be part of India is not enough,” says Ato Yepthomi, vice-chairman of the North East Coordination Committee of the National People’s Party (NPP). The NPP is a constituent of the NEDA.

Sadly, he adds, none of the successive central governments ever took sincere interest in the Northeast.