- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Enduring the river fury: Living and losing in Assam

The gushing waters from an overflowing Brahmaputra had slithered up into Tajuddin Ahmed’s house in 2014 while he and his family were asleep. Ahmed, a resident of Digirpam char (sandbar) in Barpeta district, was not new to the annual ritual when the raging waters would swamp his house year after year. But that year was different and particularly brutal. “We could not save anything...

The gushing waters from an overflowing Brahmaputra had slithered up into Tajuddin Ahmed’s house in 2014 while he and his family were asleep. Ahmed, a resident of Digirpam char (sandbar) in Barpeta district, was not new to the annual ritual when the raging waters would swamp his house year after year. But that year was different and particularly brutal. “We could not save anything that day. My ration card, voter-ID and all other documents were washed away. Somehow, I managed to save my wife and our four children,” says Ahmed.

As flood waters submerged 27 of the 33 districts of Assam this year, the events of the fateful night started playing in Ahmed’s mind all over again. “As we sat wondering what to do next, my youngest one had asked, ‘why do floods come every year? Why is the river so angry with us?'” says Ahmed, who now lives in Guwahati and pulls a cycle-rickshaw in Rajgarh area.

Not too far away from Rajgarh, officials at the Assam State Disaster Management Authority in Dispur are also struggling to find answers to similar questions posed by a bevy of mediapersons. Why are the floods so devastating in Assam? Is there no solution to the problem?

There isn’t one reason why floods batter the state every year. While most of the rivers flow downstream in Assam, much of it is dictated by what occurs upstream. Heavy rainfall and landslide upstream increases the flow downstream and easily breaches the embankments. But according to flood-control experts, man-made problems like deforestation in hilly catchment areas, encroachment in the floodplains, destruction of natural wetlands and haphazard infrastructure development in and around the rivers have amplified the devastation.

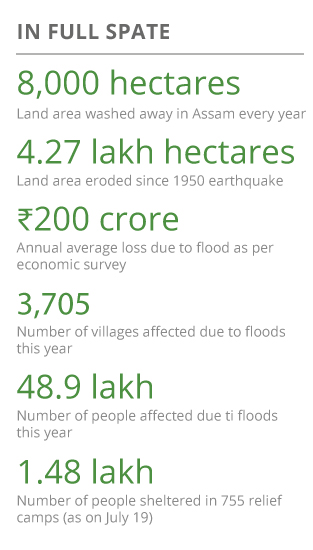

While the Brahmaputra, Dhansiri, Jia Bharali, Barak and Kopili rivers are in full spate every year, the scale of the problem has been amplified with massive erosion caused by the surging waters. The floodwaters generally take 15-20 days or more to recede, making life difficult for both humans and animals. Every year floods in Assam lead to severe fodder scarcity in Kaziranga, Manas National Park, Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary, Orang National Park and other wildlife habitats. All these areas are prone to flooding.

Also, it’s at this time of the season that wild animals become more vulnerable to poaching as they stray outside their natural habitats in search of food. A few days back, video clips of a Royal Bengal Tiger resting on a bed in a village home after emerging from an inundated Kaziranaga National Park (KNP) took the entire nation by storm.

Rofiqul, the scrap dealer from Harmoti village in the southern fringe of the KNP in whose home the tiger took refuge, says in this part of the world where floods are an annual occurrence both men and animals have learnt to live with it.

However, for the KNP the flood is a “necessary evil”, says Dr Rathin Barman, the joint director of the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI).

Kaziranga’s landscape is dominated by tall elephant grass. It provides fodder for large herbivores such as the park’s famed one-horned rhino. After the flood water recedes, the park’s floodplain gets a fresh layer of nutrient-reach silt that helps the growth of elephant grass and other vegetation. It also replenishes water bodies, Barman explains.

Barman may have his reasons to call the floods a “necessary evil”, but the state cannot ignore that the situation is likely to worsen in coming years. According to a recent report, rise in temperatures due to climate change would further increase the frequency of floods at the end of the century (2071-2100).

In Assam, the annual mean temperature has increased by 0.59 degrees Celsius over the last 60 years (1951 to 2010), and is likely to increase by 1.7-2.2 degree Celsius by 2050. According to the State Action Plan for Climate Change, extreme rainfall events will increase by 38 per cent.

Possible solution and what govt has done

For those who have been helplessly witnessing their homes getting washed away every year, there seems to be little hope. Only a decade ago, the family of Mantu Mandal (40) from Golaghat’s Mitham Chapori owned 36 bighas of land (in Assam, a bigha is 14,400 square feet) and was relatively affluent. “Now we are left with just this house, a part of which was also washed away by the gushing waters of the Dhansiri River in last year’s floods,” rues Mandal, who believes “neither God nor the government wants to help the poor”.

Mandal’s anxiety is shared by many experts in the field as well. To tackle the deluge of flood woes, the state water resources department has been relying on some archaic measures that were conceived back in 1950s. These measures are obviously inadequate.

“The first Indian policy of flood management by the Government of India back in 1953 has little utility at present. The measures prescribed for both long-term and short-term implementation such as embankments and storage projects have been found to be highly problematic scientifically, economically and politically,” writes Partha J Das in NEZINE, a Guwahati-based web portal. Das heads the ‘water, climate and hazard’ division of the Aaranyak, a scientific and industrial research organisation.

Taking a fresh look into the problem, the state government has embarked on an ambitious ₹40,000 crore Brahmaputra dredging project to retain more water in the river. But again not many are convinced that the project will yield the desired results as the Brahmaputra has the second-highest sediment yield per square kilometre in the world.

“Dredging is a superficial answer to the challenge of drainage congestion and managing floods. It will be a futile exercise because during monsoon there is a daily input of 2.12 million metric tons of sediments into the Brahmaputra,” says Dr Jogendra Nath Sarma, a retired professor of applied geology at Dibrugarh University.

So, is there no way out?

Given the state’s geographical and climatic condition, Sarma says, it would be difficult to fully contain floods. “That is why the focus should be on flood preparedness and minimising its impact.” Sarma, who has authored several books on the Brahmaputra, suggests Assam could learn a lesson from neighbouring Bangladesh, which in recent years has been able to reduce the loss of lives and properties considerably.

“Firstly, Bangladesh has put in place an effective and early warning mechanism. It has also built flood shelters — large raised platforms where people can seek refuge from the on-rushing floodwaters — with proper facilities for men and animals,” says Sarma.

The neighbouring nation has also been encouraging farmers to adjust the cropping pattern, adjusting with the rainfall pattern and flood season. Experts, including Sarma, believe that these measures could be easily emulated in Assam. Apart from saving lives, the main challenge is to reduce the loss of possessions and homes.

Ahmed couldn’t agree more. Who would understand the pain of losing home better than him? After the 2014 floods washed away his home and all belongings, Ahmed had gone to Jiribam in Manipur looking for a job with the help of an old acquaintance. In the absence of documents to prove his Indian citizenship, he was branded an illegal migrant by a vigilante group that beat him black and blue, before pushing him back to Assam.

Today, Ahmed is a stranger in his own country and still looking for an answer to his son’s question. “Why is the river so angry with us?”