- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

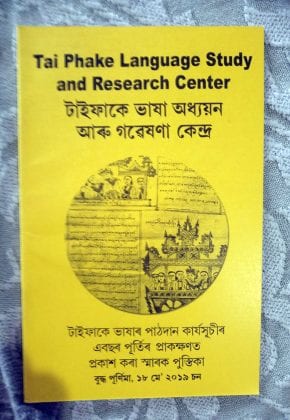

Endangered Indian languages face threat of extinction

On the banks of Burhi Dihing river, a tributary of Brahmaputra in eastern Assam, resides a group of tribals called Phakials. Originally from south China, a small section of the tribe had in 1775 crossed the Pat Kai hills of Myanmar and settled in Assam. More than two hundred years later, there are just about 150 families left of the community in the village. With that number, they also...

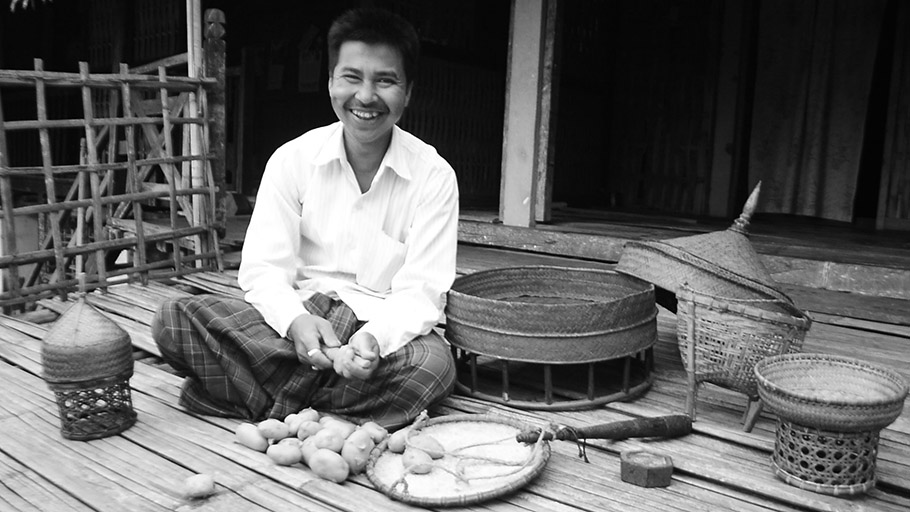

On the banks of Burhi Dihing river, a tributary of Brahmaputra in eastern Assam, resides a group of tribals called Phakials. Originally from south China, a small section of the tribe had in 1775 crossed the Pat Kai hills of Myanmar and settled in Assam. More than two hundred years later, there are just about 150 families left of the community in the village.

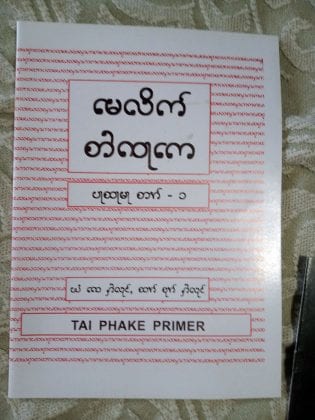

With that number, they also face another threat — that of the extinction of their mother tongue — Tai Phake, which belongs to the Thai sub-group of the Sino-Tibetan family of languages.

Despite efforts, preservation of the language has taken a beating, as most people in the community are bilingual, speaking Assamese too, to engage with the outside world. Tai Phake is used only within the house or the community.

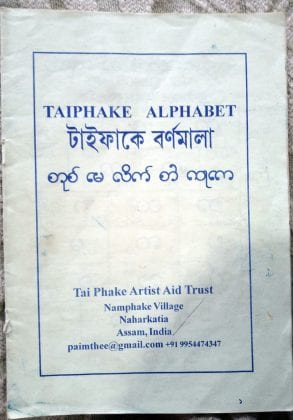

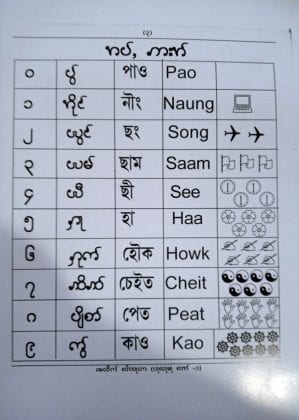

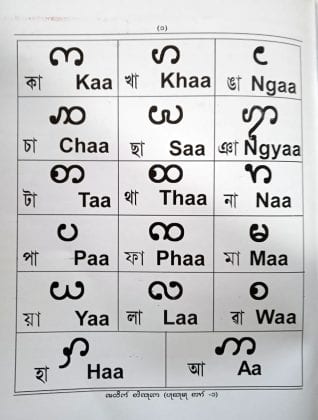

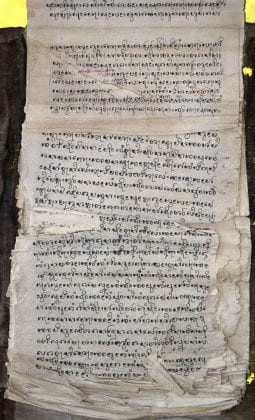

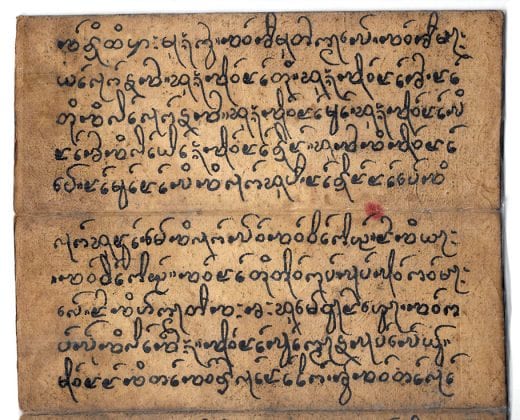

It has a script preserved over centuries and passed down generations. But with less than 2,000 people speaking the language globally — Tai Phake speakers are scattered across nine villages in Assam: Nam Phake, Tipam phake, Bor phake, Man Mau, Nam chai, Man long, Nang lai, Ning gum and Phaneng around Margherita town in Tinsukia district — the influence of majoritarian languages over their Tai Phake is a cause of concern for community members. Besides, many have migrated to bigger cities where the primary language remains different from their mother tongue, and gives little scope for using the language.

“Revival of the language is possible only if livelihood opportunities are created based on the language,” says Ngi Kya Weingken, a villager. “The local language is spoken only at home, and many do not even know writing unlike some of us. Assamese, and not Tai Phake, remains the medium of instruction in schools.”

For him, the local language offers an opening to preserve the community’s history, customs and traditions, in an otherwise majoritarian world that largely shuts its doors to linguistic minorities like the Phakials.

Weingken, who’s in his late 40s, does not want his language to disappear. As Tai Phake was not being taught in schools, he and other like-minded people in the village formed a local committee and started taking special classes over the weekend for children aged between 10 and 18 years to read and write the language.

Though it’s an additional burden for the kids, it is perhaps the only way to take the language forward, says Than Won Hailoung, who teaches Tai Phake to 25-30 kids every week on the government school premises.

Global threat

The issue is not just with Tai Phake. Kota and Toda in Tamil Nadu, Kuruba and Koraga in Karnataka, Naiki spoken in Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh, all face the threat of extinction.

According to the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco) report published a decade back, 197 languages in India, including Tai Phake, are considered endangered.

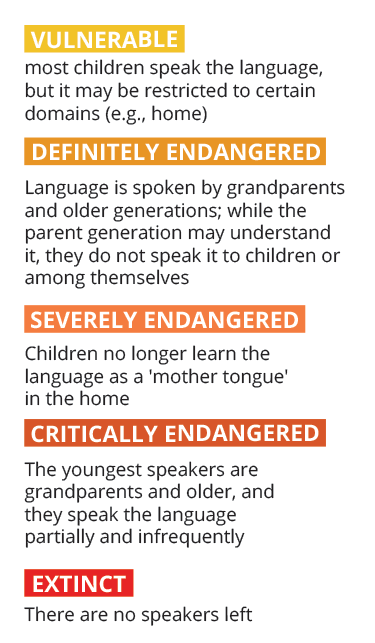

These are further divided into four subcategories — vulnerable, definitely endangered, severely endangered, and critically endangered. Most of these languages are spoken in the Northeast.

In 2016, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution proclaiming 2019 as the International Year of Indigenous Languages. The forum also pointed out that 40 per cent of the estimated 6,700 languages spoken around the world were in danger of disappearing.

Considering the fact that indigenous people are often isolated both politically and socially in the countries they live in, the UN announced that it would promote and protect endangered languages and improve the lives of those who speak them.

Forced relocation, illiteracy, migration, educational disadvantages, and discrimination and alienation of certain communities have been said to lead to erosion of a language, which in practical terms, may fall out of daily use.

Government’s efforts

Linguists and activists feel there is little that the Centre has done or is doing for endangered languages. And they fear that with the one nation, one language thought, many of the smaller languages will completely disappear.

Many feel that these languages should be included in school and college curricula, else it would reduce their ability to provide a livelihood, and result in migration which in turn could lead to cultural and knowledge loss.

According to Ganesh Devy, veteran linguist and chairman of People’s linguistic Survey of India, who spearheaded a movement to identify different languages in the country, there are about 780 languages in the country at present.

India is among the four countries (Nigeria, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea) in the world with the highest number of languages.

His team of 3,000 volunteers are in the process of documenting these languages even though they receive no help from the government.

Devy rues that even though the country’s Census 2011 estimates there are 1,368 mother tongues, it arrives at 121 languages (22 scheduled and 99 unscheduled) finally, much lesser than what his team identified. Many have questioned the manner in which the government ignores languages which are spoken by fewer than 10,000 people.

Although the government allots finances for the development of languages, many feel that majoritarian languages grab the lion’s share of funds.

A decade back, the National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities under the Ministry of Minority Affairs, had suggested continuous evaluation/monitoring of the education scenario among linguistic minorities, set up special cells in the concerned state or Union Territory as well as in the central government. It also suggested that the Census Commissioner should provide data on smaller communities, whose population is below 10,000 so that affirmative action can commence irrespective of their numerical strength.

Besides, the Commission also asked that minority language-speaking people be given preference in jobs and education, majority communities be provided opportunities to be acquainted with minority languages and cultures.

Much of this remains unimplemented.

In 1969, the Indian government established the Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL) in Mysore to research and document Indian languages. The Ministry of Human Resource Development even launched a scheme called ‘Protection and Preservation of Endangered Languages of India’ in 2014 to enable CIIL to protect, preserve and document all mother tongues/ languages of India spoken by less than 10,000 people. Linguistic experts say not much has come in the way of actual outcome.

CIIL director DG Rao says they have documented about 70 languages and are in the process of preparing primers for another 20 odd languages.

“There are operational difficulties. Lack of government data on languages is a concern. Even though the unofficial data suggests more languages (1,100 languages including 250 extinct ones) in the country, CIIL domains are restricted to UNESCO report and Census data which says 121 languages,” Rao said.

They also aim to document these languages and later look into reviving and revitalising them and then talk about reservation for linguistic minorities, he says, adding that the onus lies with the state governments and not the Centre.

“First, the states need to implement teaching kids in their mother tongue at the school level. That’s itself is not happening in many states,” he adds.

One language row & the way forward

Though Rao categorically refused to comment on the political furore over one-nation one language and its impact on CIIL’s work, he feels that one cannot be forced to learn a particular language.

Devy, on the other hand, takes a firm stand, saying “Constitution has given us the right to speak the language of our choice. There is no national language.”

He opines that the government should address the development deficit and think holistically to create more livelihood opportunity around a language.

“Students will learn the language that commands the power of money (say English, Hindi, Kannada…). That is no reason for a language to go down. Languages will survive only when there is a livelihood opportunity,” he says.

The University Grants Commission has set up a special committee and wrote to Devy saying that the linguistic survey work should be immortalised and they’d like to release a very big grant. Eventually, the grant was never released.

The government further said that it has no plans to develop web servers for local languages even as the current web servers support all the 22 recognised languages.

Devy suggests that the state should follow the multilingual education (MLE) system followed by Chattisgarh, Orrisa and parts of Andhra Pradesh, where schools teach the local language at the primary level.

The MLE materials in Chhattisgarh have been prepared in 7 languages: Gondi (Kanke), Gondi (Dantewada), Halbi, Sargujiya, Kudukh, Chhattisgarhi and Sadri.

Another linguistic expert, Dr Sandesha Rayapa assistant professor at Linguistic Empowerment Cell in Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, says art form such as folk songs and films play a major role in propagation of any language, particularly with the help of technology using which people today learn things.

“Languages are not static. They are dynamic. So efforts should be made to spread activity-based learning than force fit a language through textbooks and language studies,” he says.

Rayapa cites the example of Bhojpuri and Awadhi that became popular (revived) through the visual medium.

“Once Bhojpuri was considered as the language of rural populace. But today, because of its popularity through songs and movies, the language has gained much prominence in the in last 15 years,” she adds.

Until the government steps in to preserve and promote these language, it is people like Weingken and Hailoung who act as catalysers of these endangered languages.