- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Digital divide exposes India's neglect of tribal students

Sixteen-year-old Sreedevi has to walk at least 5 km from her home in Poochukottamparai tribal settlement in Tamil Nadu’s Tirupur district just to get a workable mobile phone signal. Sreedevi recently made headlines after scoring 95 per cent in her Class 10 board exams and became the first one from the forest-dwelling Muduvar tribal community to do so. However, she didn’t come to know of...

Sixteen-year-old Sreedevi has to walk at least 5 km from her home in Poochukottamparai tribal settlement in Tamil Nadu’s Tirupur district just to get a workable mobile phone signal.

Sreedevi recently made headlines after scoring 95 per cent in her Class 10 board exams and became the first one from the forest-dwelling Muduvar tribal community to do so. However, she didn’t come to know of her results until a journalist from neighbouring Kerala — where she went to a government residential school — reached out to her family.

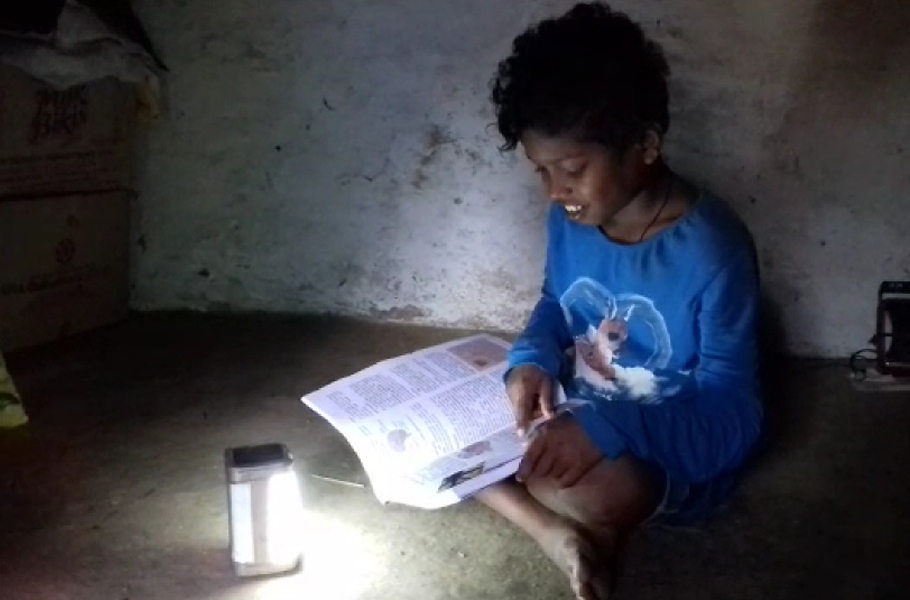

After the nationwide lockdown was imposed because of the coronavirus, Sreedevi had returned to her tribal settlement deep inside the Anamalai Tiger reserve. The isolated settlement lacks roads, electricity and access to mobile phone network. The families, including Sreedevi’s, don’t even have proper houses. While three of her exams were held in March before the coronavirus struck, she took the rest in May. (Unlike most school boards, Kerala conducted the rest of the exams during the lockdown.)

Two months back, the Kerala government had arranged a special bus to ferry her from the Tamil Nadu-Kerala border to the school so she could take her exams. But to catch that bus and reach the checkpost, the young girl and her father had to travel nearly 80 km in a two-wheeler.

“God bless the journalist who called us. That’s how we came to know of her results,” says her father Chellamuthu.

But Chellamuthu’s worries about his daughter’s education is far from over. As Sreedevi readies to take her online classes for higher secondary level — a rare feat for girls from her community — the father-daughter duo are at a loss trying to make sense of using a laptop and cellphone in the absence of mobile network and intermittent power cuts.

With help pouring in from different quarters, Sreedevi for now has managed to get a laptop with a solar charger. “We still don’t know what to do with the network problem. Online classes [by Kerala schools] haven’t started as of yet. So it’s a relief for now. However, it’s not the same for other children in our hamlet who study in nearby schools run by Tamil Nadu government,” Chellamuthu says.

Most of the tribal children in Sreedevi’s village study at a primary school inside the forest with just one teacher. After that they either have to go to a residential school away from home or drop out. Most drop out.

The situation isn’t any different for T Arunkumar of Anbu Nagar tribal hamlet in Anaimalai Taluk. With schools shut down because of the pandemic, the Class 10 student is confronting the same dilemma as many others. Arunkumar has no clue on how to access online lessons.

The Tamil Nadu government has initiated video recorded classes for students of 10 and 12. The government also started televised classes on Kalvi TV — the state government’s education channel. But Arunkumar is unable to access any of these classes because there is neither a television nor electricity connection at his home. The mobile phone connectivity too is poor.

“Even if we pay money and get a mobile phone or television set, we cannot use those gadgets because of lack of power supply. Despite several requests to the authorities for power supply and network facility, our demands have fallen on deaf ears,” says R Thangavelu, Arunkumar’s father.

While most of the students in tribal settlements in and around Anaimalai Taluk struggle for basic facilities, many in other parts of the state are forced to take up work in neighbouring farms to make ends meet. For instance, most children from Kondagai tribal hamlet in Erode district have moved along with their parents to farmlands in the plains to work and earn.

“Even in normal times our children hardly have access to good school education. Nor is there any scope for learning or adapting to such technological changes at home. That’s why we mostly admit them in government residential schools. But when your living conditions are so wretched, how do you concentrate on studies?” asks Krandhi, mother of a Class 10 student. She and her family, natives of Kondagai village, have now been working in a sugar farm at Sathyamangalam.

Krandhi is grateful that her son was promoted to the next class this year based on his marks from previous exams. “If that wasn’t the case, it was next to impossible for him to take the exams during this pandemic,” she adds.

Although she wants her son to continue school once it opens, she has no clue how he would access classes on TV or online.“We live in small rooms provided by the farm owner. Once the work gets over, we will have to move to another place. We can’t afford a television set with such meagre earnings nor can we demand one from our owner. Who will buy a TV for farm labourers?” Krandhi lets out a nervous laugh.

While the digital divide across India is not a new phenomenon, the coronavirus outbreak has laid bare the technological inequities that afflict the rural areas and tribal districts.

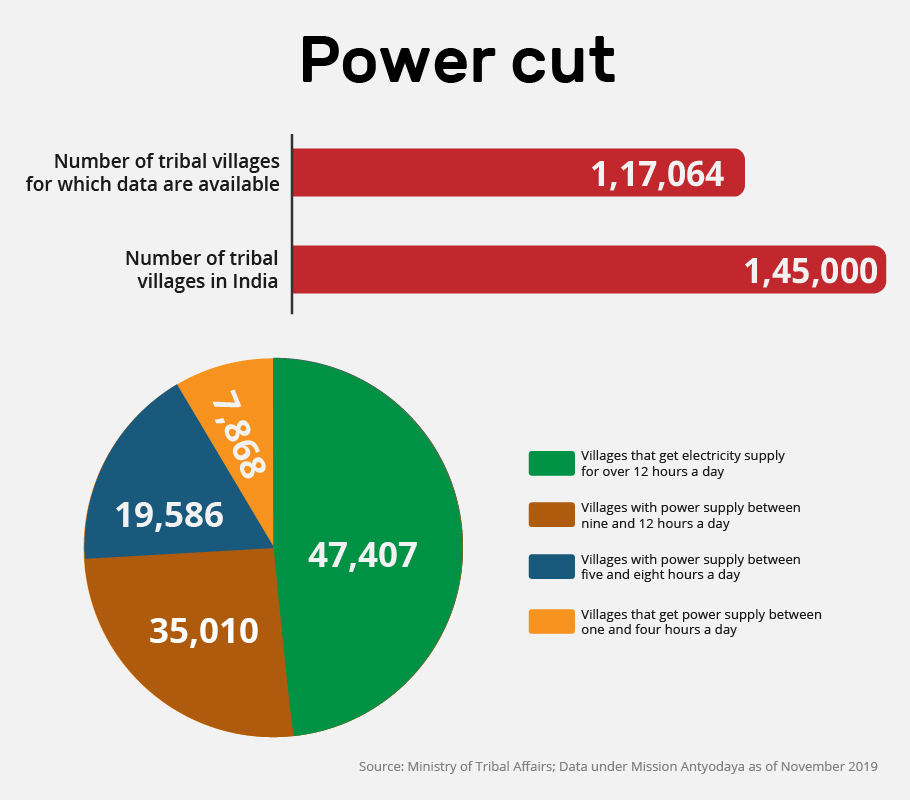

By the central government’s own admission, as many as 27, 721 villages in India do not have access to mobile services. When it comes to tribal villages in particular, the situation looks darker. Around 1.1 lakh villages go without electricity for more than 12 hours a day. That’s almost one-sixth of the total villages in India.

In such a grim scenario, activists in Tamil Nadu ask, how is it possible for tribal children to access classes online or on TV? Even though government records say only 28 villages in Tamil Nadu don’t have access to mobile services, educationists working on the ground claim there is a huge difference between having mobile connectivity and actually getting a workable signal.

“In Erode district alone there are over 100 tribal hamlets where they don’t have mobile connectivity. A few villages that have connectivity are fraught with poor signal. Most of the time people have to climb atop hills to get signal,” says SC Nataraj, director of SUDAR, an NGO working to provide education to tribal children

VS Paramasivam, head of Tamil Nadu Tribal Welfare Association (Coimbatore unit), says at least 25 tribal hamlets in his district do not have mobile connectivity.

“Mobile connectivity to village panchayat offices doesn’t mean connectivity for the whole village. Going by the data, if only 28 villages lack mobile network connections, why are tribal students in these settlements struggling to access video lessons?” he asks.

This is something the state government failed to foresee completely, they argue. “When most states are on a wait and watch mode without putting pressure of online and TV classes on the children, Tamil Nadu too could have waited a bit longer and postponed the academic year. We still have enough time to start the next school year,” says educationalist Prince Gajendra Babu.

Although there have been apprehensions about online classes in the states with high tribal populations, most of the states are mulling to reopen schools as the number of active coronavirus cases are falling.

Jharkhand, one of the states with a high tribal population, has reportedly issued a standard operating procedure to ensure strict safety measures against the spread of the virus once the schools reopen.

Similarly, Chhattisgarh too has also been planning to reopen its schools once the Union government issues relaxations for Unlock 3.0.

Nataraj though has an alternative suggestion. He feels the government can make education accessible to tribal students by bringing teachers to community centres in villages. “Most of these children are first generation school-goers. Their parents too are completely clueless about their children’s future. For them, education means going to school. It’s difficult for them to comprehend or adapt to technological changes like online or TV classes all of a sudden.”

Moreover, he says, these families can’t afford TV or mobile phones. “How can we expect tribal people who are mostly dependent on forest produce to buy TV or smartphones,” Nataraj asks.

Tamil Nadu Tribal Welfare Association president P Shanmugam feels it’s the government’s responsibility to take care of these children. “They have come forward to learn overcoming decades of social prejudice and neglect.”

Now that their parents have realised the need for education, Shanmugam feels, the digital divide is pushing them back.

-year-old Sreedevi has to walk at least 5 km from her home in Poochukottamparai tribal settlement in Tamil Nadu’s Tirupur district just to get a workable mobile phone signal.