- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

COVID-19 has hit India’s children hard, and from all sides

Children have been left to endure huge losses due to COVID-19 with thousands becoming orphans in a matter of a few weeks.

Inside a government-run child care centre in southwest Delhi’s Jaunapur, eight-year-old Tanvi (name changed) looks exhausted from crying, her face drained of colour. According to Prakash, one of the caretakers, Tanvi hasn’t talked much ever since she arrived three weeks ago. “She has been mostly crying. When she is not crying, she is repeatedly asking to see her parents.”...

Inside a government-run child care centre in southwest Delhi’s Jaunapur, eight-year-old Tanvi (name changed) looks exhausted from crying, her face drained of colour. According to Prakash, one of the caretakers, Tanvi hasn’t talked much ever since she arrived three weeks ago.

“She has been mostly crying. When she is not crying, she is repeatedly asking to see her parents.” Prakash doesn’t know how to tell the eight-year-old that she can’t see her parents. “They are no more.”

Nothing seems to distract Tanvi from her misery. Her wails punctuate the silence of the hallway every now and then.

The single-storeyed building has more than a dozen rooms that include a play area and a reading room as well. Yet no one could convince Tanvi to go near the toys or the neatly stacked-up books on the shelves. Outside, the empty swings in the playground swaying in the wind further accentuate the grief and loneliness housed inside the little hearts.

Tanvi is among 59 children who have landed at the child care home (for girls) after losing both their parents to the second wave of Covid-19. Deep in their hearts, these little girls know that their lives have changed horribly, and forever.

“The slightly older ones do have an inkling that they have been orphaned, others like Tanvi are too young and inconsolable to be told about the tragedy that has befallen them,” Prakash tells The Federal.

Many of these girls, he adds, are still under the impression that their parents are ill and recovering in hospital, that they will come and take them home soon. “Tanvi is one of them. Given the sensitivity of the matter, we are constantly in touch with child care experts to deal with the situation.”

But Prakash doubts whether these children will ever come to terms with their loss anytime soon.

The second wave of COVID-19 pandemic, which appears to be abating slowly, has already left a long trail of unusual death and devastation. While there was hardly any family completely untouched by the virus, children have been left to endure huge losses with thousands becoming orphans in a matter of a few weeks.

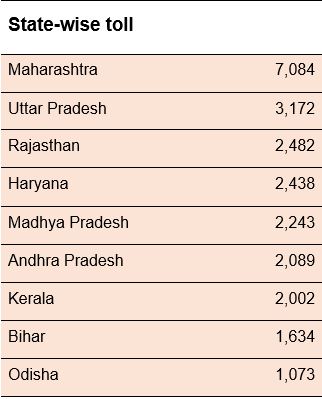

According to the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR), as many as 30,071 children have either been orphaned, lost one parent or abandoned in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis. The NCPCR, a statutory body under the Ministry of Women and Child Development (WCD), informed the Supreme Court about the numbers according to data submitted by different states and union territories as of June 5.

Siddharth K, an independent researcher, calls this the tip of the iceberg. “With many states hiding the numbers—West Bengal not even giving it—the number is expected to be more than double that the NCPCR has shared.”

Recently, the Supreme Court pulled up the West Bengal and Delhi governments after the NCPCR said these states were not cooperating in furnishing the latest data on the number of children who have lost their parents due to coronavirus.

“That the Supreme Court, the NCPCR, central and state governments have started taking note of such incidents very seriously, is good to begin with. But a lot needs to be done to heal our children who have been hit hard by Covid in different manners,” he adds.

Siddharth has reasons to be anxious because apart from losing their parents, there are many others who are still lucky to have their parents around but are not fortunate enough to escape acute poverty and malnutrition.

Beg, borrow or go hungry

In the wake of the pandemic, many families are having to send their children out to work and to beg. While it’s difficult to find the estimated number of such children in absence of any official figures, surveys by non-profit organisations and the chaos on roads across cities and towns expose the ground reality.

The mounting joblessness among adults and rising cost of food, exacerbated by high fuel prices, have left children visibly affected.

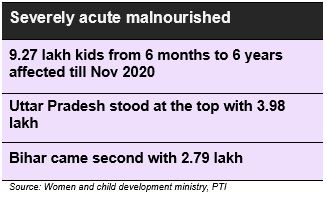

By the government’s own admission, there are nearly a million malnourished children—aged six months to six years—identified across the country until November last year. The information was given by the Women and Child Development Ministry in response to an RTI query from the Press Trust of India.

Pravesh Kumar, a daily wage earner in Gurugram, says before the lockdown he used to send ₹8,000-10,000 home in Bihar every month. “During the lockdown last year, I did not earn anything. I had gone back to Bihar. I worked there but couldn’t manage to get more than ₹3,000.”

Kumar says he, along with his wife and children, couldn’t afford to eat proper meals. “My children would often go to bed hungry.”

He is back in Gurugram now but the situation hasn’t improved much. “I am not being paid the same wage as before the lockdown. I can only send ₹4,000-6,000 every month now, depending on the income.”

While this is enough to feed his children back home, Kumar says, it’s “of course not enough to feed them well”.

Arun Kumar, retired professor of economics, JNU, says as economic activities slowed down from the beginning of the pandemic, many lost their jobs which is directly impacting their food consumption capacity. “The unemployment rate is increasing continuously. People are losing jobs, especially those engaged in manual labour who are solely dependent on every day work.”

“Even in normal times, the poor of this country struggle to manage two square meals. Now that their income is hit badly it has directly affected their consumption of food. They are now struggling to manage two meagre meals of just rice and dal twice a day. Their children naturally are left malnourished,” he adds.

To put things in perspective, India still has 94 percent of its population working in the unorganised sector. Of that, according to professor Kumar, nearly 40 percent are daily wage labourers.

“The income of these 40 percent, nearly 20 crore people or 200 million, were directly taken away during the pandemic. And when the government says only one million children are malnourished, that is not possible. The number is way higher.”

What has added to the chaos is the shutdown of schools and anganwadi centres. The children are not getting mid-day meals and nutritious foods from anganwadi centres in their villages. While a few states did announce schemes to take mid-day meal schemes to homes and provide students of its schools dry rations or allowance in view of continued closure of schools, the rising number of malnourished children casts doubts on the benefits of such announcements.

In May, the Centre announced to directly transfer mid-day meal cooking cost to children studying in Class 1 to 8 in government schools. The amount—about ₹100 to each student—though is hardly sufficient to provide nutrition security, say Right to Food activists.

A report in The Hindu quoted Dipa Sinha, associate professor of economics at Ambedkar University, saying that ₹100 per child amounts to less than ₹4 a day even if it was a monthly payment.

“With schools being closed due to Covid-19, children are being given cash in lieu of the mid-day meal in some places and dry rations in others. Either way, the quantities/amounts are too low to be even adequate for one nutritious meal a day.”

With fears of an imminent third Covid-19 wave looming large even before the nation has overcome the second wave, it is feared that these malnourished children will be at a greater risk of contracting the virus. While hunger and malnutrition compound vulnerability to the virus as nutrient deficiency weakens the immune system, malnutrition could prove to be a huge comorbidity in the third wave, experts have already warned.

Wriggling out of the cycle of poverty looks difficult for these children further with most of them forced to drop out of schools.

Forced out of school into marriages, labour

At least six million children in India have dropped out of school from March 2020, according to the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER). There is a sharp jump in out-of-school children in the 6-10 age group that has gone up from 1.8 percent (in 2018) to 5.3 percent (in 2020) and among all children up to 16 years from 4 percent-5.5 percent, according to ASER.

“The reasons for the children dropping out of schools can be many. One of the main reasons is the job or income loss of parents. In India, the Gross Domestic Product is at the all-time low since independence. The unemployment rate also stands high,” says Sunil Kumar, an education activist.

According to a Pew Research Centre report, the first wave of Covid-19 pandemic may have shrunk India’s middle-class population by 32 million below the poverty line in 2020. The second wave of Covid-19 is expected to cause more damage. The unemployment rate reached a four-month high in April as localised lockdowns imposed in many states have impacted over 70 lakh jobs.

The situation is such that the parents of a daughter sought funds on Twitter for her education. Both the parents have lost their jobs due to Covid-19 pandemic and have assured that they will return every penny they get once they get a job again.

Another reason is the digital divide in India. In the pandemic, the schools are teaching online, but 38.2 percent of the children in India do not have access to the internet, computer or smartphones, ASER survey revealed.

As a result, more and more children are getting pushed into the vicious cycle of forced labour, human trafficking and marriages, especially the girls, some as young as Tanvi, others older.

In a Haryana’s village, officials of the State Commission for Women prevented the parents of a 16-year-old girl from marrying her off for the second time in a year. At first, they stopped her marriage in August last year and now in May. various reports suggest that child marriage has increased by 20-70 per cent in different parts of the country.

Preeti Bhardwaj, chairperson of the Haryana State Commission for Women, says, “Cases of child marriages, especially of girls, have increased nearly 50 per cent in Haryana amid Covid-19. We received around 104 complaints compared to 50 normally every year. The parents, especially economically backward, want to get their girls married to save the expenses incurred on them.

“COVID-19 has made an already difficult situation for millions of girls even worse. Shuttered schools, isolation from friends and support networks, and rising poverty have added fuel to a fire the world was already struggling to put out,” UNICEF executive director Henrietta Fore earlier said in a press release.

Apart from child marriage, child trafficking and child labour have also increased. A study by the Campaign against Child Labour (CACL) reveled that the child labour has increased from 28.2 per cent to 79.6 per cent in Tamil Nadu, mainly because of Covid-19 and closure of schools. The CACL survey showed that the increase is 280 percent among the vulnerable communities. A similar increase in numbers was witnessed in other parts of the country as well.

According to Kailash Satyarthi Foundation (KSF), there is a four fold rise in trafficking and child labour across the country with Jharkhand and Bihar being the worst-hit states.

“As the pandemic has hit every sector heavily, children are most vulnerable in such a situation. Busses filled with children are going out of UP, Bihar and Jharkhand. We have rescued many of them,” Ajit Singh of KSF describes the horror.

According to him, these children are mostly trafficked to big cities for work. “As companies are cutting costs, they are engaging children, whom they hire for a paltry salary. Usually, grown-ups charge Rs 8,000 for the same work which children do for Rs 3,000 to Rs 4,000.”

Poor parents, he adds, hardly have an option to stop their children from going out.

“They feel at least their children will get to eat.”