- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

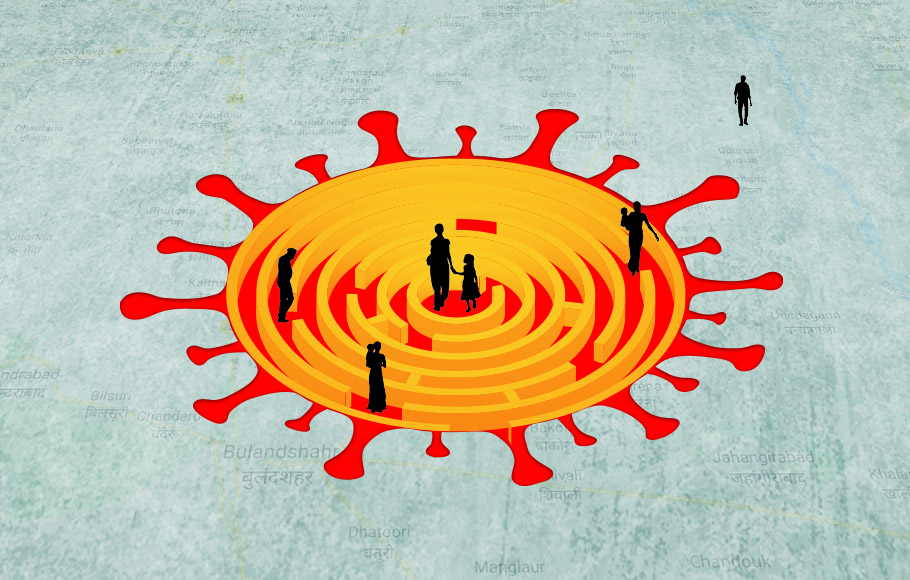

COVID-19 has unmasked India — the poor are on their own

Unfortunately for the poor, the Coronavirus continues to chase them as barriers have come up in their own villages, which wish to safeguard them against the impending disease.

On March 24, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi was addressing the nation announcing a 21-day countrywide lockdown, nearly 200 million people were glued to their television sets making it one of the most watched events ever in the history of Indian TV. Halfway through the live event, however, many urban Indians abandoned the speech and rushed on their two-wheelers and cars to nearby malls,...

On March 24, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi was addressing the nation announcing a 21-day countrywide lockdown, nearly 200 million people were glued to their television sets making it one of the most watched events ever in the history of Indian TV.

Halfway through the live event, however, many urban Indians abandoned the speech and rushed on their two-wheelers and cars to nearby malls, super stores and even corner ‘kirana’ shops to buy as many and as much groceries as they could. Digital savvy netizens and millennials immediately started placing orders online.

A colleague who happened to be at a marketplace when the event was unfolding was simply overwhelmed by the sudden rush of people. “They are buying as if there is no tomorrow. Is it an apocalypse now?” he wondered on a WhatsApp group.

What he and perhaps many among the political class missed was a brewing parallel trend: a large number of urban poor were moving in the opposite direction — towards interstate bus stands and railway stations. They were rushing towards their homes nestled in small towns, villages and far off hinterlands. They were surviving on daily and weekly wages and it was unimaginable for them to live in a city without work for 21 days, leave alone the uncertainties thereafter.

Rise of the middle class, fall of empathy

In 1991, when prime minister PV Narasimha Rao opened up the Indian economy, he abolished the license raj. The industrial policy was altered and the private sector was given a boost. His then finance minister, Manmohan Singh, who later went on to become prime minister himself, led the reforms with a mindset that “a crisis should never be wasted”.

This led to a growth of the enormous middle class. Foreign investors were drooling at the prospect of witnessing a market that would be at least 300-million strong. The economic pundits were estimating much more — they said it could go up to over 400 million people.

In the following decades, several revolutions swept India. The boom in information technology, mobile telephony and massive expansion in the services sector placed more disposable income in the hands of the burgeoning middle class. In turn, they fuelled the growth of the real estate sector and automobiles. Expansion of public infrastructure led to growth of mass transport and civil aviation.

The impact of this was all pervasive. The trends in mass media advertisements changed from basic innerwear to more sophisticated luxury goods. In the relatively better-off southern states, the marketeers had begun to talk of a “lucrative replacement market”, where consumers could paint their homes once in two years. It’s not without reason that US President Donald Trump was pushing for the sale of Washington apples and Harley Davidsons in India. He said India should stop calling itself a developing nation.

What was conveniently forgotten in this maddening growth of the middle class accompanied by the cacophony of the often illogical and insensitive social media was the existence of urban poor who were trying to find a foothold within the nooks and crannies of Indian cities.

The urban Indian, perhaps in his new-found wealth and arrogance, has been routinely ignoring these people, at times even refusing to recognise their presence. What they conveniently forgot was their contribution to overall growth of the economy and their own well-being. Electricians, painters, plumbers, drivers, house helps, car washers, pet walkers and courier boys have been trooping in and out of their lives without telling their employers how much they lessen their day-to-day burdens.

As the insecurities of the middle class grew, gated communities sprouted almost everywhere. As urban conveniences expanded ATMs, private establishments, schools, colleges, malls and cinema halls required a new class of employees called security guards. Although poorly paid and often housed in uncomfortable portable cabins, they still marched on. In the jobless growth of the economy, the job of a security guard at least gave them some liquid cash which they could send back to their homes.

The arrival of the gig economy further expanded this class of people. Some of them took loans to be part of ride-hailing companies such as Ola and Uber. Many others became part of food delivery aggregators. As the mobile app-based companies grew, more and more employees were absorbed by the sector. Most of them went about their jobs without any employment security or insurance. They rented small, dingy rooms within the city, commuted on public transport and survived on street food. Whenever they were struck by illness or calamity, they would simply rush back to their homes in the villages.

The same instinct overtook them when the lockdown was announced by Modi. They simply packed their bags and started moving towards the inner land. The rulers, failing to grasp the enormity of the impending crisis, simply suspended bus services (not to forget that Indian Railways had already stopped running passenger trains since March 22). Although the intention was to curb the spread of the deadly Coronavirus by forcing social distancing, the effect was just the opposite. The poor started emptying out silently from the cities as they faced an existential crisis. For them, poverty is a bigger killer than the deadly virus.

The administration and the political class completely failed to recognise their problems, laying bare the fact that politicians who claim to be mass leaders have little or no connect with their own citizenry whose votes they rely so much upon to win an election.

Social distancing — a luxury for the poor

Coronavirus has been punishing its victims mercilessly without any differentiation. In fact, leaders of powerful nations, including prime ministers, queens, prince and princess besides a host of celebs, have been infected by the virus. COVID-19 has been spreading across the developed, developing and underdeveloped nations without any bias.

Many African countries erroneously believe that Coronavirus is a rich man’s disease. In fact, some of them have been dismissing it as a “white man’s burden”. In India, the poor had little idea of the origin of the pandemic. The disease arrived in India through Indians travelling back home from abroad and foreign travellers coming to India. States which are more globally connected through commerce, trade and services were the first to be hit. It slowly seeped to secondary and tertiary levels which is described as community spread in medical parlance.

For poor economies, social distancing in itself is a luxury. The average poor with a family of four lives in single-room shacks in the cities. He is young and perhaps could survive with the infection. But he may infect his aged parents back home. Although India has grown, its growth has been uneven. It has ignored health, education and social infrastructure, the areas various governments promised to take over once it started moving towards globalisation. Agriculture has been in the ICU for a while as the farmer has never managed to get his return on investment.

The sharp right turn of politics globally has exacerbated nationalist tendencies and its powerful rulers have been targeting migrants. Although the key differentiation is “illegal migrants”, its definition is never explicitly spelled out by the politicians as they believe ambiguity helps them in targeting communities and polarising voters.

In India, the importance of a migrant population — which is estimated at over 400 million — is never fully recognised. In Delhi, many living in high-rise apartments believe that they are hiring “illegal Bangladeshi migrants” (read Muslims) as they have little option. In the southern states, xenophobic tendencies try to rear their heads every now and then, citing regionalism as the underlying cause. Southern states which are relatively better off, but are rapidly ageing are attracting migrant labourers from the north to keep their economies chugging.

The Centre has rolled out “One nation, one ration” scheme to ensure minimum supply of foodgrain through a universal ration card to a migrant. The states—wary of the Centre taking away their federal rights—have been slow in implementing the idea. The Direct Benefit Transfer schemes which provide subsidies directly to the bank accounts of its beneficiaries has helped the poor. But clearly these are not enough to bridge the fault lines between the urban middle class and the poor.

The prime minister’s act of calling himself a “chowkidar” or his eulogisation of “pakora economics” have proved that these were nothing more than empty rhetoric. When the calamity struck, the poor realised that they have to go back to their native places to save their lives. The fact that the government thought of sending aircraft to rescue its citizens abroad, but forgot to even anticipate the plight of the urban poor displays its disconnect. Buses were deployed fearing perhaps bad publicity when the poor began to march and the media went ballistic.

Unfortunately for the poor, the Coronavirus continues to chase them as barriers have come up in their own villages that wish to safeguard themselves from the impending disease. They are being stopped at village borders and asked to get tested before they enter their homes.

Over time, the virus may lose its steam and go away. Scientists around the world would soon find an antidote or a vaccine. But can the poor survive the onslaught till then?

There could be a silver lining in the Corona cloud if it succeeds to jolt governments — in states and at the Centre — and its people in the cities to start thinking about their poorer neighbours. Or is it just wishful thinking?