- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

COVID-19: For lab technicians, it's a litmus test

With India scaling up the tests for COVID-19, the limited number of testers in the country are racing against time to identify cases quickly and prevent further spread of the contagious virus.

“There is (work) pressure, but we are not regretting it. We cannot be complacent to sit back and relax and say no, I need a break. That is not possible in this situation.” For Dr Amrutha Kumari B, nodal officer of Virus Research and Diagnostics Laboratory (VRDL) and in-charge of COVID-19 test laboratory at Mysore Medical College and Research Institute (MMCRI) in Karnataka, the last 45...

“There is (work) pressure, but we are not regretting it. We cannot be complacent to sit back and relax and say no, I need a break. That is not possible in this situation.”

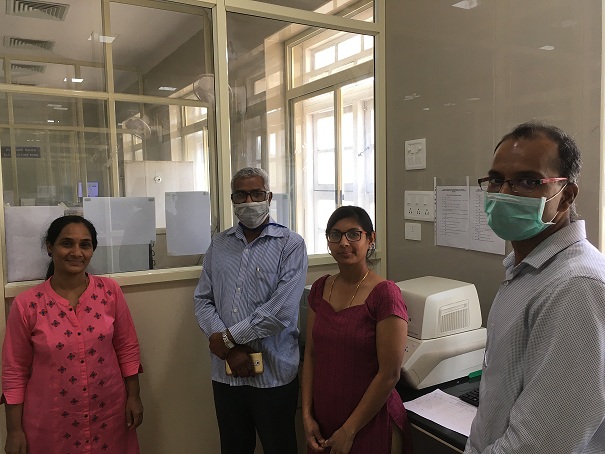

For Dr Amrutha Kumari B, nodal officer of Virus Research and Diagnostics Laboratory (VRDL) and in-charge of COVID-19 test laboratory at Mysore Medical College and Research Institute (MMCRI) in Karnataka, the last 45 days have been quite hectic. Day and night since early March, her five-member team has been testing samples for coronavirus.

“We don’t know when it is night, when it is day. We almost end up putting in 14–16 hours every day,” she says.

Inside the lab, Kumari and her team work in biosafety cabinets — which are enclosed, air-conditioned workspaces lit well with tubes throughout the day. No light or air comes in from outside.

Kumari, who has been working as a clinical microbiologist for the past 17 years, with three of those in Mysore Medical College’s virology lab, says this is the time when she can contribute the most as the situation demands it and she doesn’t regret the work pressure.

“This is the first time in my 17-year experience I am encountering something big,” Kumari says.

“Where my expertise is useful, I will put maximum effort into it,” she says, adding, “Maybe we are compromising certain things, but that’s fine for now. The present condition demands it.”

By compromise, she means wearing personal protection equipment (PPE) all through the day, except for food/toilet breaks, which may be just twice a day. Sometimes with the PPEs, it becomes difficult for them to breathe. With scarce resources, they tend to take fewer breaks so that fewer PPEs are used per day. On an average, a person uses two PPEs every day. The situation is similar in labs across the country, including private ones, testing for COVID-19.

Also, from 100 samples a day in March, Kumari and her team are now testing around 200 samples daily, and it sometimes goes up to 300 in extreme cases. With Karnataka testing more with each passing week, their workload has been increasing by the day.

It worsened when Mysuru’s Nanjangudu turned into a COVID-19 hotspot after a man working in Jubilant Lifesciences, a pharmaceutical company in the town, contracted the virus and later, it spread to others in the company. That was one of the reasons for Mysuru to become the second highest district in Karnataka with COVID-19 cases, 88 of the total 445 cases.

“There is (work) pressure, but we are not regretting it. We cannot be complacent to sit back and relax and say no, I need a break. That is not possible in this situation,” she says.

Testing process

The testing process is not a simple one or a one-person job. Kumari explains it takes 3–5 people working in three different stages to establish whether a sample is COVID-positive or not.

She says initially, two sets of swab samples from a suspected patient’s throat and nose are taken by a concerned hospital, which will log and code the details into a registry, and then send the samples to the testing labs.

In the lab, the virus genome is extracted from the sample. The Ribonucleic acid (RNA) in the sample is put through what is known as real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test, which probes for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) specific genome. If that specific genome is detected, the person is said to be COVID-19 positive, otherwise s/he is negative.

Kumari says extracting the genome from the sample is the crucial stage where they take extra precautions so as not to come in contact with the potentially infectious body fluids.

“We take all precautions to prevent the spread to the person who’s handling it as well as to the environment. We see to it that the surfaces and the room are not contaminated, and the person handling it is not getting infected. We’ve trained them to handle it,” Kumari says.

Hiring and training

Expecting a rise in demand for testing, the MMCRI lab has taken in 10-12 post graduate microbiology students and are getting them trained in the testing process.

“While they would have the basic knowledge of the tests, we have to train them to adapt to the current situation,” Kumari says.

The diagnostic tests that they do are similar to that of swine flu, and use the same methodology, except that they are done in bulk. But in the case of swine flu, the spread was not as high as coronavirus, and so there wasn’t as much work pressure.

Families worried

Far away from the lab, Kumari says their families are scared of their work but that they cannot express it because they think she and the others are doing a service to the country.

“This is entirely necessary for the community, and it is important internationally too. So, they are putting up with us despite not dedicating any time to them,” she adds with a bit of remorse.

Kumari says she chose the profession because she wanted to serve people, and that is also why she left clinical practice and opted for microbiology and testing as her domain which gave her the flexibility of doing clinical practice as well as laboratory service and research.

Divya V, 24, who works in Neuberg Anand Reference Laboratory, a private COVID-19 testing lab in Bengaluru, narrates a similar story of family members cooperating with what they do at work.

While they both are proud of what they are doing and their families are supportive, Divya says her neighbours do not know what she does and she fears they might think she’s working in a risky environment of being exposed to the virus.

Asked if this crisis would encourage more students to take up microbiology and lab testing as a career, she says people are afraid to enter labs fearing infection. “With the kind of fear psychosis that has set in, I really doubt how many would come into this,” she says.

However, Dr Kumari feels that more than lab researchers like her, it is the doctors who are at a greater risk as they come in direct contact with patients and one may not know which patient carries how much virus load.

“We take necessary precautions wearing PPEs and work in a biosafety cabinet. So the chances of us getting infected is less. As of now laboratory-acquired infection for coronavirus has not been reported so far,” she says, and adds quickly, “We have been handling the tests since nearly 50 days now, and none of us have fallen sick.”

Are we testing enough?

On the national and international front, Kumari expects the number of COVID-19 cases to go up in the next 15 days as the situation looks unlikely to stabilise in the immediate future.

More the tests, the better it would be, she says.

Globally, the number of COVID-19 cases stood at over 2.54 million, with more than 175,000 fatalities, as on April 23. Many countries have raised their testing rate to contain the spread of the virus. India, however, has been found lagging behind in this regard by many experts, although the government has defended its action.

With the arrival of new test kits from China by mid-April, testing had increased from 60-65 people per million in the first week of April to 363 people per million as on April 23. However, this is in no way comparable to the number of tests done in other countries, such as US’ 11,428 tests per million or Spain, Germany and Switzerland’s over-20,000 tests per million.

Even African countries like Ghana and Rwanda are testing more than India, with 2,207 and 537 tests per million population, respectively, as per Worldometer, a data portal that among other things has been tracking coronavirus numbers.

As of April 23, India had tested five lakh samples through 194 government labs and 82 private labs, of which 21,700 individuals confirmed positive.

After Congress leader Rahul Gandhi raised concerns over India’s low testing, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and the country’s health ministry observed that we are not testing less.

“In countries like Japan, one out of 11.7 tests turn out to be positive, which is among the highest in the world. Italy tests 6.7 persons for one positive test while the USA tests 5.3 persons and the United Kingdom 3.4,” ICMR’s Dr Raman R Gangakhedkar said at a press conference.

India, on the other hand, had one positive case out of 24 tests, he said, dismissing comparisons with other countries.

Even if there are some handicaps, Kumari says the government’s actions so far have been partially in the right direction.

She wishes that more tests are done, even if that means more sleepless nights for her, as she feels early identification would help isolate the infected and take precautions.

“The only way to reduce our task is not by testing less but by increasing the manpower. That said, the government is trying to do what they can,” Kumari says, even as she fears there might be a shortage of PPEs in the coming days and hopes the government would address the issue immediately.

(This story is part of a series on frontline personnel in the fight against COVID-19)