- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

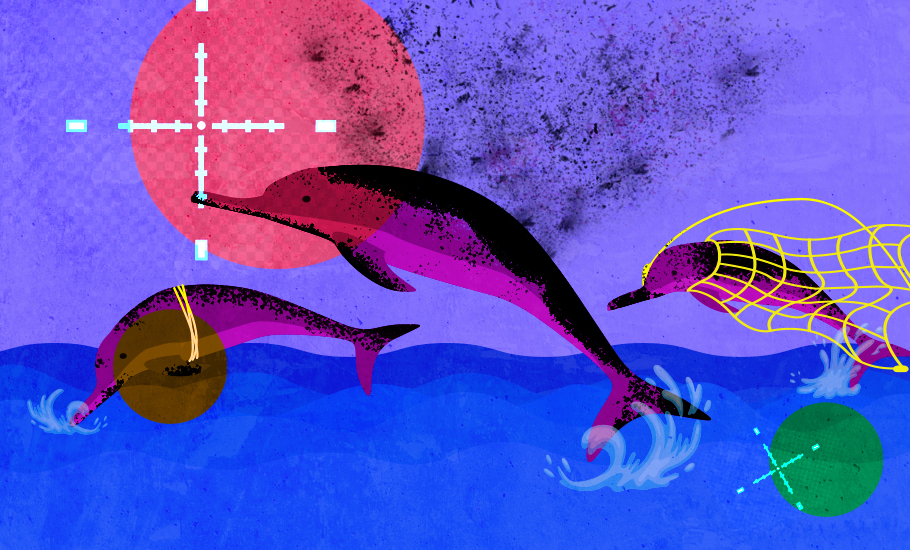

Could Project Dolphin be India’s great leap to save the endangered species?

With the number of dolphins going down, spotting of the species is becoming rarer and rarer, ironically sprouting a tourism industry on dolphin sightings in various parts of India.

For 45-year-old Subhamoy Bhattacharjee it was nothing short of ‘divine intervention’ last September. Bhattacharjee, who works with the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), waited for around two weeks, training his camera lens at the mighty Brahmaputra flowing through the heart of Guwahati. He was told the Pandu Ghat area was the best place to sight a Xihu (the rare Gangetic dolphin, as it is...

For 45-year-old Subhamoy Bhattacharjee it was nothing short of ‘divine intervention’ last September. Bhattacharjee, who works with the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), waited for around two weeks, training his camera lens at the mighty Brahmaputra flowing through the heart of Guwahati. He was told the Pandu Ghat area was the best place to sight a Xihu (the rare Gangetic dolphin, as it is called in Assamese language) in the city.

His leap of faith paid off on the day of Mahalaya that heralds the advent of Durga Puja when suddenly a flash of grey popped up giving him a fraction of a second to capture the moment.

With the number of dolphins going down, spotting of the species is becoming rarer and rarer, ironically sprouting a tourism industry on dolphin sightings in various parts of the country, particularly Goa.

Elsewhere in the world though nautical lore is ripe with stories about pods of dolphins saving divers and swimmers from shark attacks. These tales, though incredible, show a special, spiritual and magical bond that humans share with the cute-looking mammals.

Ancient Greeks believed dolphins were the messengers of Poseidon, the god of the seas. They were tasked to bring the deceased to the Fortunate Isles, a legendary island paradise inhabited by the heroes and heroines of Greek mythology.

According to some etymology, the ‘dolphin’ gets its name from the Greek word delphys (delphus) meaning ‘womb’. It was also associated with Atargatis, the Assyrian mother goddess of fertility, vegetation and nourishment.

Even the early Christians had a spiritual bond with the aquatic creature with a long and slender snout. They viewed it as a symbol of resurrection.

Contrary to past beliefs, the symbol of resurrection is now facing threat of extinction in various pockets, unless vigorously protected against fishing.

In India too, the dwindling dolphin population needs literal resurrection to prevent them from going extinct.

Experts believe that metaphorical elixir of life could be the Project Dolphin that Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced in his Independence Day speech to save both river and marine dolphins in the country. The project will lay special emphasis on protection of Gangetic river dolphin, which was declared as the national aquatic animal in 2009.

Dolphins in India

The Gangetic river dolphin (Platanista gangetica), which was officially discovered in 1801 in Hooghly river by William Roxberg, is also the official mascot of Guwahati in Assam where the mammal is known as Xihu.

As per the last count, there are about 2,500-3,000 Gangetic dolphins currently inhabiting the Ganga-Brahmaputra-Meghna and Karnaphuli-Sangu river systems spread across Nepal, India and Bangladesh.

There are also 152 Irrawaddy dolphins (Orcaella brevirostris), a species of oceanic dolphin found near sea coasts and in estuaries and rivers in parts of the Bay of Bengal, recorded in Chilika Lake in Odisha and Sundarbans National Park in West Bengal.

Besides, two genetic variations of humpback dolphins are found along the Indian coastline—the Indian Ocean humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea) along the west coast and the Indo Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) by the east coast.

A few of the surviving Sousa plumbeas even roam the coastal stretch in Mumbai and can be spotted in pockets such as the Malabar Hill, Worli, Marine Drive and Alibaug. The cetaceans can also be seen moving in groups along the Honnavar, Gokarna Karwar in Karnataka and Goa coasts, apart from some other coastal areas.

The proposed 10-year conservation programme announced by Modi will be on the lines of Project Tiger, which has helped increase the tiger population in the country.

Why Dolphins need to be protected

Much like the tigers in forests, dolphins are the powerful ‘predators’ in the water. They mainly eat fish and squids and are themselves a source of food for some sharks and other creatures and thus help maintain the river and marine ecology.

“Without dolphins, the animals they prey on would increase in number and their predators wouldn’t have as much to eat. This would disrupt the natural balance in the food chain and could negatively affect other wildlife and the health of the ocean environment,” says the World Wildlife Fund.

The latest project will be implemented by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change while the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) has been given the responsibility to prepare the blueprint. According to WII director Dhananjai Mohan, the institute has already started working on the project focusing on each and every aspect of its conservation.

At an individual level, the conservation efforts, however, started long back with initiatives such as the Conservation Action Plan for the Gangetic Dolphin 2010-2020 prepared under the auspices of the National Ganga River Basin Authority.

The West Bengal government earlier this year decided to set up a breeding centre for the endangered Gangetic dolphin at the riverside town of Katwa in East Burdwan, where the freshwater mammal is often sighted.

But despite such initiatives and the species granted protection under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, its numbers have dwindled, forcing the government to go for a more comprehensive and integrated project.

Fresh impetus

The Ministry of Environment and Climate Change in a statement has said the project would engage the fishermen and other river/ocean dependent populations to protect dolphins as well as to reduce water pollution, encourage sustainable fishery and other livelihood options.

It will also work in close tandem and support of various ministries, departments, scientific organisations and civil society groups etc.

“It’s definitely a good initiative and, if properly implemented in a coordinated effort, it will definitely help preserve the dolphin population in India,” believes Abdul Wakid, a dolphin expert associated with several conservation efforts to save the cetaceans.

Dr VN Nayak, marine biologist and retired professor (marine biology) of Karnataka University, Karwar, is happy to see that efforts are being taken to conserve the dolphin species.

Nayak says while there is no study done to indicate the number of species (Sousa plumbea) in the region, he feels as of now there is no threat from the fishers or from the local population.

“While we do not have polluting industries and also naval activities are restricted in these areas where Dolphins are sighted, there’s not much of a threat we see for now.”

That said, while there are no boating activities for tourists in Karnataka, tourist specific dolphin-sighting boat rides are organised in certain beaches in South Goa. Nayak says it can be regulated if we look from the conservation point of view.

“In Karnataka and Goa, once in a while the dolphins are washed ashore because of injuries. Also, there’s tremendous awareness among the fishers and they do not resort to catching them. Even if they get caught in nets, by chance, they are released back to the sea,” he adds.

However, from 1976 to 2013, about 766 entanglements/incidental catch of dolphins in fishing gear has been reported from Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh. Highest fishing-related mortality was reported from Kerala (526) followed by Tamil Nadu (231), a 2016 Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute report said.

The big threats

Killing, habitat fragmentation by construction of dams and barrages, indiscriminate fishing and increasing boat traffic are identified as some of the key factors that reduced the Gangetic river dolphin population.

“Dolphins are killed both accidentally and deliberately. Sometimes they get killed after getting entangled in the fishing nets. But they are also killed deliberately as dolphin oil has huge demand in illicit markets for its supposed medicinal properties,” says Wakid.

Oil extracted from blubber of the Platanista gangetica is also used as a fish attractant by many fishermen in India and Bangladesh.

A recent study found that vessel traffic on the Ganga waterways are also severely impacting the dolphin population as underwater noise gets five-time louder than on the water surface, according to Wakid.

For the project to be successful, experts feel that along with focusing on community participation and scientific interventions, emphasis should also be given on regional cooperation particularly for the preservation of Gangetic dolphins.

“These animals do not realise boundaries and have tried to find habitat wherever possible. Hence, regional cooperation is very important in conserving them,” pointed out JK Jena, DDG (Fisheries Science), ICAR during a recent webinar.

The webinar tried to explore the impact of COVID-19 on the ecosystem health of rivers and its dolphin population.

Most experts opined that a coordinated approach is needed to synergise trans-boundary efforts and to develop a regional conservation programme.

Wakid, too, feels regional cooperation is essential for the project to succeed. However, he says, earlier efforts to get these countries on board for a joint effort somehow were not very successful.

Will the neighbours come on board this time around to ‘resurrect’ the dwindling dolphin population? The success of Project Dolphin will largely depend on the answer to this tricky question.