- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Coronavirus is not man-made, only the rumours are

By analysing the public genome sequence data from SARS-CoV-2, researchers have convincingly concluded that "SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus", putting to rest all suspicions of bio-weapon gone astray.

Debunking the conspiracy theory that the SARS-CoV-2 was a secret Chinese bio-weapon that somehow escaped from labs into the community, a recent research has put the rumours to rest and asserts that the origin of the virus is ‘natural’. Published online on March 11 in the reputed Nature Medicine, the team* of researchers led by Kristian Andersen, associate professor of immunology...

Debunking the conspiracy theory that the SARS-CoV-2 was a secret Chinese bio-weapon that somehow escaped from labs into the community, a recent research has put the rumours to rest and asserts that the origin of the virus is ‘natural’.

Published online on March 11 in the reputed Nature Medicine, the team* of researchers led by Kristian Andersen, associate professor of immunology and microbiology at Scripps Research Institute, California, US, concluded that the SARS-CoV-2 strain presently ravaging the world “originated through natural processes”.

SARS-CoV-2 was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei province, China in early December 2019 and has currently spread to 110 countries. As of March 18, 2020, around 207,860 novel pneumonia COVID-19 cases have been confirmed, and about 8,657 deaths have been reported.

The proximity of the Wuhan Institute of Virology, a research institute under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, to the outbreak locale led to speculations in media that “coronavirus may have leaked from a lab”.

By analysing the public genome sequence data from SARS-CoV-2 and comparing it with the related viruses, Anderson and his team have convincingly concluded that “SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus”, putting to rest all suspicions of bio-weapon gone astray.

A simple primer on the virus

A virus is a simple, small organism. It just has a core where the genetic material (DNA or RNA) are housed and a cover of capsule protecting the core. While the genetic material code for the concoction of the essential proteins and replication, the capsule acts as a vehicle to transfer the virus from cell to cell in a host organism (human, animal or plants).

Viruses freeload. The virus can’t replicate themselves or build new viruses on their own. They cannot make proteins needed for its sustenance. For survival, and reproduction, they have to invade and embezzle the host cell mechanism to make its own copies. They have to covertly infiltrate and stealthily use the host organisms’ cell machinery. If they rupture or break to enter, the cells will die and be of no more use to the virus. The molecular ‘doors’ on the surface of the cells have to be gently unlocked, and the virus has to quietly penetrate. To this end, they cunningly manipulate the host cell mechanism to their advantage.

Cells of all living organism, from single-celled bacteria to blue whale, have to maintain their integrity even while interacting with the environment. Like a gated community, a cell wall envelopes the cell, separating it from its environment. Like the security at the gate recognises visitors before opening the gate, the cell wall opens to permit the inside-outside exchange of materials.

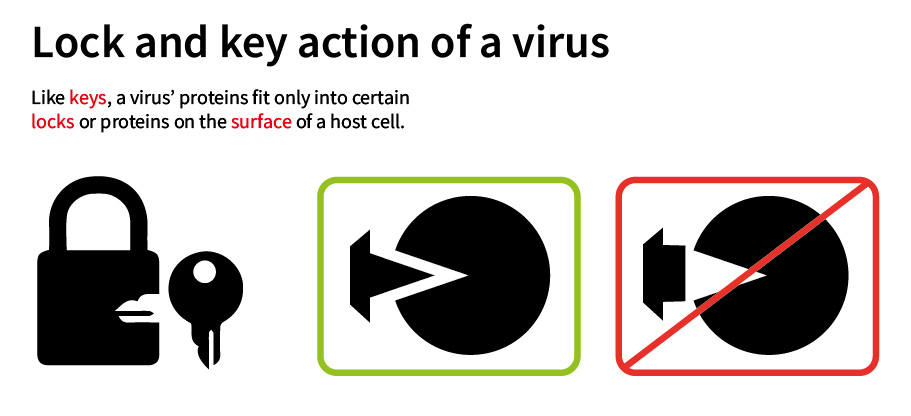

The surface of the cell wall has a protrusion called receptors. These receptors scan the approaching protein, and if recognised, trigger the opening in the cell wall, permitting the exchange of substance between the cell and its environment. The receptor-on the host cell surface can be viewed as the “lock”, specific protein as the “key”. A cell would have various types of receptors linked to different proteins it deals with.

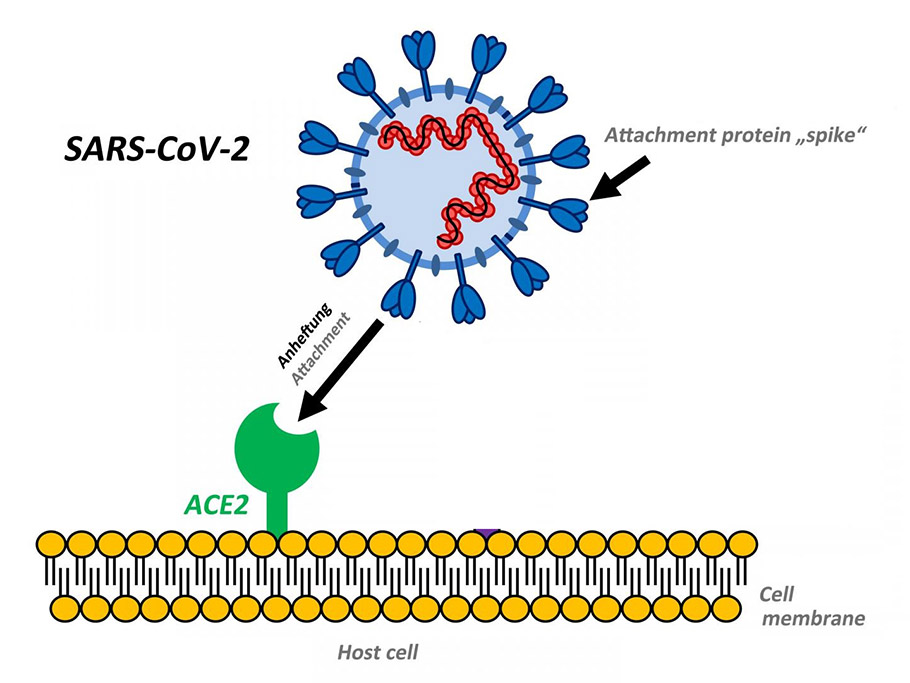

Invariably the shells of the virus have a protruding spike-like structure composed of protein projections. These arms, like projections, have two specific locations — a receptor-binding domain (RBD), that clutch and holds onto host cells and a cleavage site, a molecular crowbar that acts like the forged key. In some cases, viruses must open numerous locks, much like a doorknob plus a deadbolt lock, to invade the cell. These lock-and-key interactions are critical for viruses to successfully invade host cells.

Like a burglar using a counterfeit key to break in and loot, the virus uses the RBD and the cleavage sites to unlock the host cell. Typically, locks come in various shapes and sizes. Likewise, each organism don specific receptors that bind only with particular protein structure.

No safecracker ever can have all the duplicate keys for all the locks in the world. In like manner, each virus variety possesses keys that can only unlock a range of host organisms. Hence, all viruses cannot infect humans (or other animals). The virus that is fatal to one organism may be harmless for others. It all depends upon the molecular shape and size of the key and cleavage site on the spike protein.

Coronavirus

Like the cat-family has the tame, the rowdy as well as the ferocious tiger as its members, the Coronaviruses (CoV) are a large family of viruses consisting of a variety of unique strains that infect humans, animals and birds. Among the six strains that affect humans, 229E, NL63, OC43, HK01 have only inconsequential health impact while the MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV are deadly.

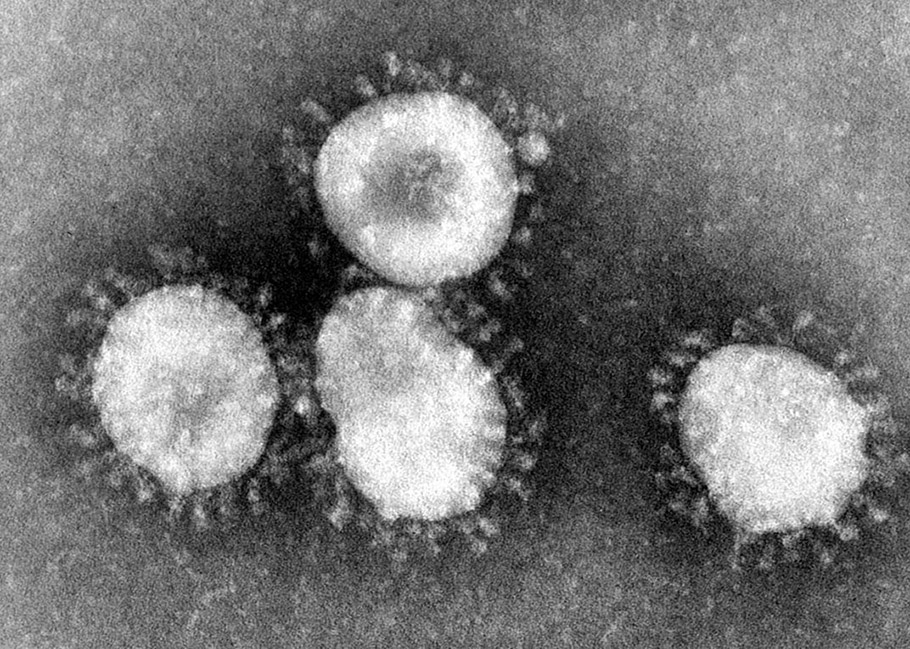

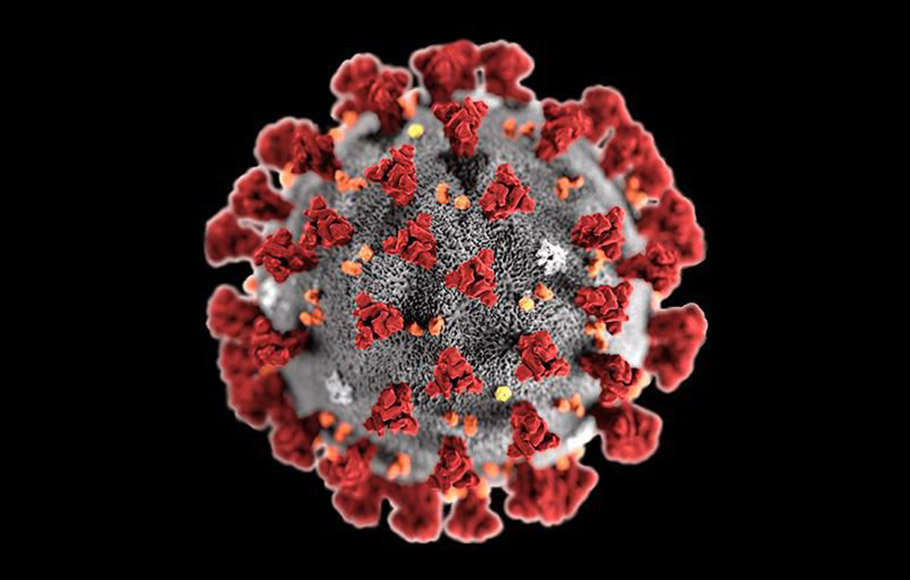

The seventh, SARS-CoV-2 was identified in 2019, and hence called as ‘novel coronavirus’. Under microscope, all these coronavirus exhibits ‘corona’, a spike-like extrusion on the surface. This looks like a crown or a corona of Sun, hence the name coronavirus.

Genome sequence

Within a few weeks of the epidemic, Chinese scientists had swiftly sequenced the genome of SARS-CoV-2. They made the data freely available to the world. An earlier analysis of the sequence had shown that the epidemic had begun with a single introduction into the human population. Once a human was infected, in the first instance, the virus was transmitted rapidly from person to person, resulting in a pandemic.

The earlier study had also indicated that the new novel strain had been detected by the Chinese medical team almost immediately after its introduction into the human population. However, the origins and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 remained a mystery.

By comparing the genetic sequence of six SARS-CoV strains, infecting both humans and animals, Anderson showed two distinct features specific to SARS-CoV-2. The RBD portion and the polybasic cleavage site of the SARS-CoV-2 were novel. From the study, they were also able to conjecture a possible evolutionary path of SARS-CoV-2 turning into a human pathogen.

The RBD portion of the SARS-CoV-2 was evolved to effectively bind on the human cell receptor called ACE2. Incidentally, in humans, this receptor is involved in regulating blood pressure. If the virus was human-engineered, we would expect it to be better than the known human pathogens. However, even though the binding was with high affinity, the interaction was neither ideal nor optimal.

The already known SARS-CoV was more optimal than the SARS-CoV-2. More optimal the binding, more widespread and deadly the disease is. If SARS-CoV-2 was designed and created as a bio-weapon, then we would expect it to perform better than known natural strains. Otherwise, what is the point of making a new artificial strain? Having a less optimal binding is like manufacturing a blunt knife.

“This is strong evidence that SARS-CoV-2 is not the product of purposeful manipulation,” said the research report.

If the SARS-CoV-2 was artificially created as a bio-weapon, then it must have been done by tinkering the backbone of a virus known to cause illness in humans. To the surprise of the researchers, the backbone of the SARS-CoV-2 resembled more with the coronaviruses that infect bats and pangolins rather than those that infect humans.

The researchers found that “all notable SARS-CoV-2 features, including the optimised RBD and polybasic cleavage site” are observed in coronaviruses in nature. From this, they rule out “any type of laboratory-based scenario as plausible”.

“These two features of the virus, the mutations in the RBD portion of the spike protein and its distinct backbone, rule out laboratory manipulation as a potential origin for SARS-CoV-2,” Andersen says.

How the novel virus emerged?

The genetic analysis has concluded that the human pathogenic SARS-CoV-2 evolved very recently. It means ancestors of pathogenic SARS-CoV-2 must have once been non-pathogenic to humans.

Based on their genomic sequencing analysis, researchers suggest two possible mechanisms for the pathogenic evolution of SARS-CoV-2 from non-pathogenic phase into a pathogenic strain. They say that either the natural selection occurred in an animal host before the zoonotic transfer of pathogenic strain to humans or the natural selection took place among humans following a non-pathogenic zoonotic transmission.

Related human pathogenic viruses, SARS emerged as a pathogen with the potential to infect human first in civets (and MERS in camels) before it jumped onto humans. Likewise, the SARS-CoV-2 virus might have evolved in its current pathogenic state through natural selection in a wild animal host before leaping onto humans. Bats and the pangolins, the researcher says, are the suspect reservoir.

If this is true, then both of the distinctive features of SARS-CoV-2, the RBD portion that binds to human ACE2 receptor and the cleavage site that opens the human cell, must have evolved into their current state before entering humans.

However, neither the bat beta coronaviruses nor the pangolin beta coronaviruses sampled have polybasic cleavage sites found in the SARS-CoV-2. This means there must be an intermediate host between human and bats/pangolin, before they entered humans. We do not have any evidence of the intermediate host or intermediate form of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. This makes this theory debatable.

Alternatively, a non-pathogenic version of the virus may have latched onto humans and then evolved into its current pathogenic state within the human population. Many coronaviruses that reside in wild mammals in Asia and Africa have RBD structure very similar to that of SARS-CoV-2.

One of this virus may have been transmitted to humans, and over time, the distinct cleavage site could have evolved within a human host. Once the virulent cleavage site was developed, the current epidemic must have been sparked.

It is established that the pathogenic version of SARS-CoV-2 emerged sometime between late November 2019 to early December 2019. If the non-pathogenic ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 evolved in the human host, then the first zoonotic event must have occurred much earlier for the polybasic cleavage site to grow to its current state. If this is so, we must find the non-pathogenic strain of SARS-CoV-2 in humans, a shred of evidence we clearly lack today.

Not just curiosity

Which of these two alternatives is true? Researchers say we do not have adequate information today to conclude. Only future research will tell. The study on the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 is not only curiosity-driven. It has public health implications.

Researchers point out that if the pathogenic form of the SARS-CoV-2 evolved in wild animals before infecting humans, then there is a probability of future outbreaks. The disease-causing strain of the virus must still be lurking darkly in the wild animal population. This strain may at any time once again lurch onto humans unleashing another epidemic. If this is the case, we need to hold our breath.

On the other hand, if the strain evolved from a non-pathogenic strain transmitted from an animal, the chances of recurrence of yet another new strain are remote. Once we are infected by a particular strain of the virus, we usually have life-long immunity from that virus.

Although we are not sure if SARS-CoV-2 infection gives life-long resistance, the current episode of the epidemic, most likely, will remain the first and last SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in human history. We can heave a sigh of relief. Only “more scientific data could swing the balance of evidence to favour one hypothesis over another”.

*The research team included Robert F. Garry, of Tulane University; Edward Holmes, of the University of Sydney; Andrew Rambaut, of the University of Edinburgh; W. Ian Lipkin, of Columbia University in addition to Andersen.

(The author is science communicator with Vigyan Prasar, New Delhi)