- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Can Nirmala Sitharaman find enough growth pills for the ailing economy?

India has been witnessing an unusual trend wherein the political temperature has remained high since the last six years. This may impact not only domestic productivity and investment but also global opportunities.

On February 1, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman will present the Union Budget 2020-21. As usual, there are intense speculations and expectations over the nature of the budget. Some expect it to be more of the same, wherein the government would announce “grandiose schemes” without actually spelling out where it would find the money to fund them. Others think it would...

On February 1, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman will present the Union Budget 2020-21. As usual, there are intense speculations and expectations over the nature of the budget. Some expect it to be more of the same, wherein the government would announce “grandiose schemes” without actually spelling out where it would find the money to fund them. Others think it would be “please-all, populist” budget with a cut in personal income tax rates and sops to farmers. And yet others expect “big-ticket reforms” that may help the economy in the long run. But one thing they all agree is that the finance minister has a tough task at hand.

The economy hasn’t fallen into a recession but the indicators paint a gloomy picture. GDP growth is the lowest in 11 years. Investments by companies have hit a 17-year low. Private consumption, or money spent by individuals to buy goods and services, is lowest in seven years. Manufacturing growth has slumped to the worst in 15 years. Agriculture, which sustains 44 per cent of India’s workforce, has registered the slowest growth in four years. Finally, unemployment levels are the highest in 45 years.

How did we get here? In 2014, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi took over the reins of the government, there was an air of expectancy among the rich and the middle class. Even a large number of rural population voted for a government that promised “achche din”. The carefully crafted image of Narendra Modi as a leader who means business was bought by a huge section of the populace. The tales of scams, policy paralysis and economic mess left behind by UPA-2 had made the electorate wary, and they expected the new leader to bring in rapid development and economic growth.

Besides the massive mandate, low and stable international crude oil prices were a bonanza for the government. But the government seems to have frittered it all away. Instead of facing the future, it has been looking at the rearview mirror, trying to correct what it perceives as the “mistakes of the past”. However, it started reopening the wounds of the partition, redefining the status of minorities and reassessing the decisions of the previous regimes.

It would be difficult to differentiate how many people voted for Modi’s development plank and how many opted for his party’s Hindutva vision. The government, bolstered by a return mandate in 2019, seems to have opted for the latter course at the cost of the economy. It scrapped Article 370 in Kashmir and chose to ignore an already-pulverised opposition. A verdict favourable for the Hindus in Ayodhya came as a booster shot. It then quickly got on to redefine and widen the ambit of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and proposed a pan-India National Register of Citizens at a time when the trust deficit between the government and a section of citizenry, especially minorities, is running low.

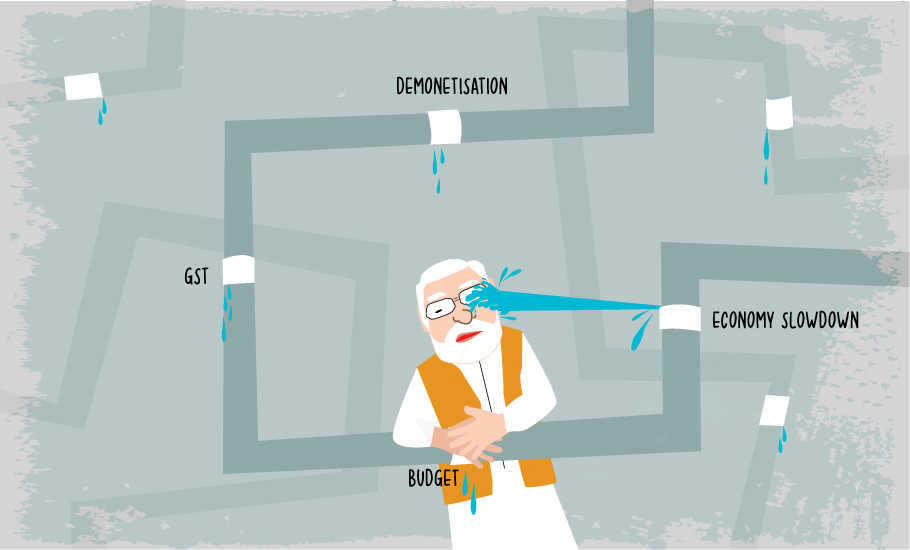

The Modi government inherited the “twin balance sheet problem” from UPA-2, which meant big companies borrowed heavily from public-sector banks. Non-payment of these loans caused huge holes in both their balance sheets. The under-capitalised public-sector banks faced a crisis and the government had to step in to save these banks. Even while the economy was grappling with the problem, Modi went on a misadventure. In 2016, he demonetised high-value notes. Even before its implications could be understood, the GST was introduced in a hurry. The botched implementation of the reform compounded the matters. A global slowdown further exacerbated the problem.

The government continued to maintain its swag globally till mid-2019 as China slowed down and it was claimed that India was the fastest-growing major economy in the world. Subsequent developments have been showing a downward trend. Recently, the chief economist of the International Monetary Fund, or IMF, declared that India was not only slowing down but was also responsible for dragging the world economy along with it.

So how does the government deal with it? Economists have been debating for a while wondering whether the downturn is cyclical or structural. A cyclical slowdown would be routine following a business cycle while a structural one would be more fundamental in nature and require big-ticket reforms. Some cited the Keynesian way of stimulating the economy. The Reserve Bank of India, or RBI, obliged by cutting its lending rates to banks by 135 basis points over 15 months. But the banks could pass on the benefits only partially to its customers. With the RBI reaching its limits, it was expected of the government to step in. In a bold move, the finance ministry cut the corporate tax to 22 per cent from 30 per cent. For new investors in the manufacturing sector, this was slashed further to 15 per cent. Although the measure was unprecedented, its impact is likely to kick in only after a lag of around 12–18 months. The industry is still to respond in full measure.

The government also announced plans for spending $1.5 trillion over five years to boost infrastructure. The Centre is expected to contribute 40%, the states another 40% and the rest coming from corporates.

But the big question is where will the money come from? The Union budget has very limited scope for balancing its income and expenditure. The Union government’s earning is accounted under two heads — tax revenue and non-tax revenue. The net tax revenue of the Centre is the money it keeps with itself after sharing with the states. Non-tax revenue is the money the government earns from public-sector companies as dividends and receipts, and by divesting its shares in these companies.

Revenue expenditure is the money the Centre spends on interest payments; subsidies (food, fertilisers, petroleum products, etc.); wages, salaries and pensions of central government employees, armed forces, etc. It is estimated that in the current year, the revenue expenditure has overtaken revenue receipts by 18 per cent.

The government is also expected to spend money to create assets for the future under the section called capital expenditure. Since there is no money left, this is largely funded by borrowings and earnings from public-sector companies.

Roughly, the gap between revenue and expenditure is termed as the budget deficit. The finance minister in 2019-20 budget had estimated the budget deficit to be 3.3 per cent, but this is likely to be exceeded as the government has already spent its full-year allocations in six months. To make up for the gap, it had taken out money from the RBI reserves.

So, what do economists expect from the budget? A little honesty. They feel if the budget makes full disclosure, which means including “off-balance sheet items” that are quietly shifted to public-sector companies, the deficit would be much higher. Since already much dust has risen over the government’s economic data, such as GDP figures, unemployment figures etc., economists are expecting clearer data from the government.

The revenue shortfall is huge, estimated at around ₹3.5 lakh crore. Also, only 25% per cent of the disinvestment target has been met so far. So one suggestion to the government from some economists is to make the budget “expansionary”, meaning spend more even if the budget deficit widens. In other words, ignore fiscal prudence and focus on reviving the economy.

Therefore, the finance minister’s hands are tied. Besides routine expenditure, she needs to spend more on education and health. She also needs to address the farm sector and provide for MGNREGA and PM’s Kisan Insurance schemes. Obviously, she would be tempted to announce more schemes. There may be very little headroom for cutting personal income tax as the tax receipts are already low. All this makes her task difficult.

Some economists claim that the problems in the economy may be much more than what meets the eye. Arvind Subramanian, who till recently was the Chief Economic Advisor (CEA) to the government, has claimed that there are two twin balance sheet problems and not one as expected earlier. Another former CEA, Ashok Desai, in a write-up claimed that there are three twin-balance sheet problems — Corporates and Banks; MSMEs and informal lenders; and the Central government and RBI.

While some of these claims need to be denied or validated by the government, what is clear is that it may take a while before the economy is back on track.

Besides, there are issues which the government may consider extraneous, but which may already be impacting the economy — various protests around the country. In India, normally the political temperature goes up in the run-up to the elections. Once the elections are over and the results are declared, the temperature comes down as the government of the day gets busy addressing the day-to-day issues. State and provincial elections continue with localised impact without much ado. Since the new regime took over in 2014, India has been witnessing an unusual trend wherein the political temperature has remained high for the last six years. This may impact not only domestic productivity and investment but also discourage global investors.