- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

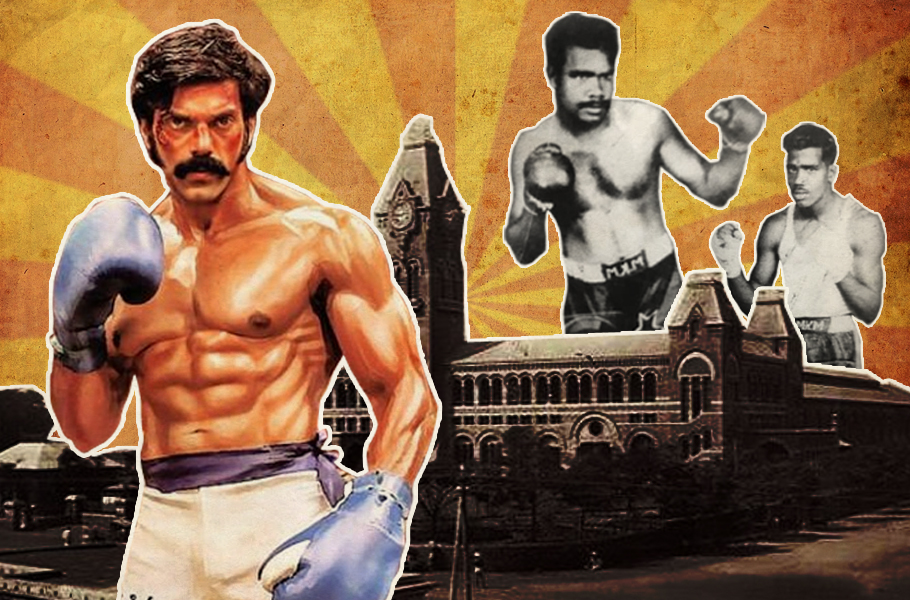

Boxing culture and the forgotten heroes of real-life 'Sarpatta Parambarai'

Pa Ranjith’s Sarpatta Parambarai, a period film set in the 1970s, centres around the clash between two boxing clans. But there is more to it | Image - Immayabharathi K

Everybody loves the underdog. From real-life Muhammad Ali to reel-life Rocky Balboa, the triumph of the underdog, as they say, is an ancient story that never fails to delight. Pa Ranjith’s Sarpatta Parambarai sets out to do the same. It does that and a bit more—by rising to the occasion at a time when Tamil cinema seems to have fallen on bad times in the wake of the COVID-19...

Everybody loves the underdog. From real-life Muhammad Ali to reel-life Rocky Balboa, the triumph of the underdog, as they say, is an ancient story that never fails to delight.

Pa Ranjith’s Sarpatta Parambarai sets out to do the same. It does that and a bit more—by rising to the occasion at a time when Tamil cinema seems to have fallen on bad times in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The period film set in the 1970s essentially centres around the clash between two boxing clans—Sarpatta Parambarai and Idiyappa Naicker Parambarai. But there is more to the warring clans—a boxing star born out of the most unexpected of places.

As an undercurrent, it also touches upon the caste conflicts and discrimination besides the politics of the time among the DMK, AIADMK and the Congress during the Emergency.

The film has been very well-received by the masses even though there has been some criticism against it for portraying certain communities in a negative light. Pa Ranjith, for that matter, is known unspooling a new genre of Dalit-centric films and putting marginalised communities at the centre stage.

But bouquets and brickbats apart—which are common to any celebrated work—what the film has really managed to achieve is to trigger curiosity about the boxing culture of North Chennai, or the erstwhile North Madras.

The games begin

A number of martial art forms were practised in Tamil Nadu before the 1920s, including silambam (stick fight), gusthi (wrestling) and kuthu sandai (traditional boxing art), etc. The modern form of boxing was introduced to India by the British.

“They introduced boxing first in Kolkata, then in Mumbai, Bengaluru and Chennai. In Tamil Nadu, the modern form of boxing was first introduced in Chennai and more particularly in North Chennai,” says historian P Veeramani.

The British introduced the game to Indians not just to popularise it here but to make people fight among themselves, and thereby keep themselves entertained, he adds.

Out of the four cities, except Mumbai, all the other cities became fertile grounds for good boxers, says Veeramani.

In Chennai, places like Royapuram, Perambur, Perambur Barracks, Periamet—all in the northern part of the city—became boxing havens.

“Royapuram then looked like a mini London, because of the Anglo-Indians. The roads were dotted with bars and pop singers performing their hearts out. Every second person used to speak fluent English. Till the 1960s, this was the scene in Royapuram. Apart from Royapuram, the Anglo-Indians also resided in and around Perambur. Then we had Buckingham Carnatic Mills, where a large number of Anglo-Indians served as officers. It was through them that boxing was introduced to the residents of Chennai,” says Veeramani.

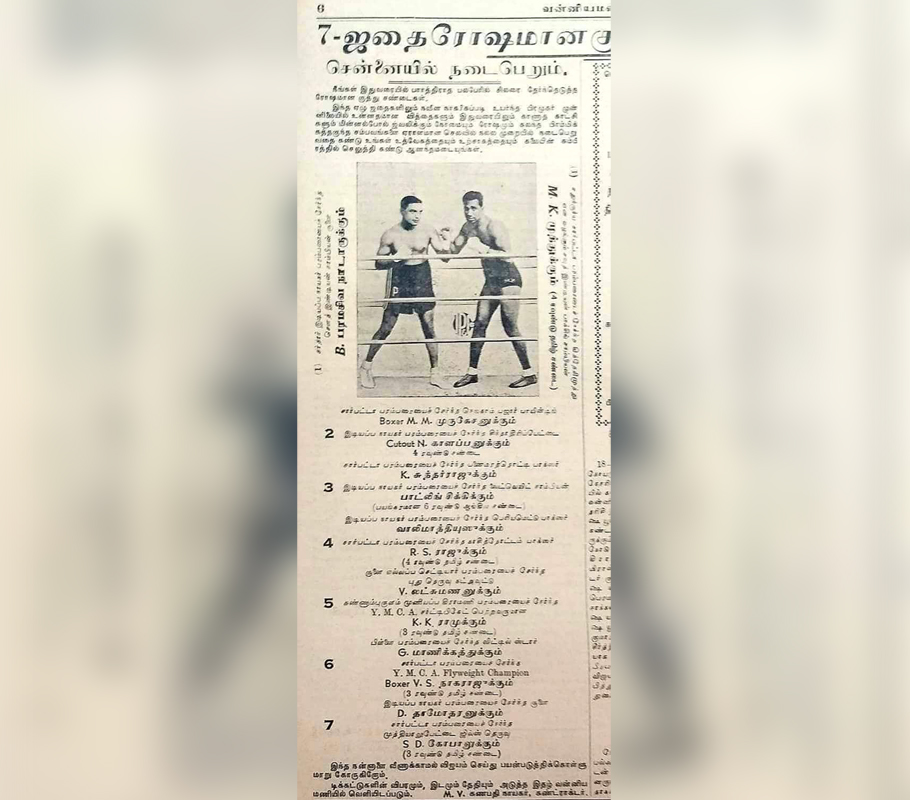

In those days, there was only professional boxing. No amateur bouts. The contractors, who were mostly from the markets of Kothavalchavadi, organised public matches twice a month. The ticket rates ranged from ₹3, ₹5, ₹10 and ₹15. There would be 10-15 ‘jathai’ (pairs) games which would most probably be conducted in SIAA grounds.

‘Parambarai’ culture

When the British introduced boxing, they first selected the fishermen from Royapuram because they had naturally well-built physiques. A place called Panaimara Thotti in Royapuram was the epicentre of boxing back then.

“It was from here that the real ‘Sarpatta Parambarai’ was born,” Veeramani says, adding that the film wrongly shows Vyasarpadi, another locality in North Chennai, as the place where boxing was introduced.

“Royapuram, Royapettai, Harbour, Sengangadai and Pulianthope were the places where the ‘Sarpatta Parambarai’ spread its wings. The other two Parambarais led by Idiyappa Naicker and Ellappa Chettiar flourished in places like Choolai, Periamet and Perambur. Since these two clans resided in almost the same region, they used to train in the same place and lived like brothers. They never fought amongst themselves. Rather, their common opponent was ‘Sarpatta Parambarai’, which had many invincible fighters,” Veeramani claims.

Idiyappa Naicker and Ellappa Chettiar were boxers who later turned into ‘vaathiyaars’ (master coaches), and the respective parambarais (lineages) were named after them. However, it is difficult to ascertain who was the real vaathiyaar of Sarpatta Parambarai.

The name ‘Sarpatta’ itself has many meanings and explanations according to different people.

“The real name of Sarpatta Parambarai was Chathur Surya Sarpatta Parambarai. The word ‘Chathur’ denotes four directions and ‘Surya’ indicates descendants of the Surya tribe. The meaning of the name in Tamil goes like this: Naangu Thisaigalilum Yaaraalum Vella Mudiyaadha Surya Kula Vazhi Vandha Puli Parambarai (The tiger-like descendants of Surya tribe who couldn’t be vanquished by anyone from all four directions),” says Veeramani.

But there are other versions of the story as well. For instance, the family of M Kitheri Muthu, one of the top boxers of ‘Sarpatta Parambarai’, has this to say. “In ‘Sarpatta’, we had players from communities like fishermen, Dalits and minorities like Muslims and Christians. All were trained together without any caste discrimination. They were dependent on each other. Hence the name ‘Sarpatta’,” says Babu, grandson of Muthu.

In Tamil, the word ‘Saarndhu’ means ‘to depend’. Since different communities depended on each other, this meaning is attributed to Sarpatta.

Some others believe that the word ‘Sarpatta’ was derived from a blending of two words ‘Chaar’ (Hindi for four) and ‘Patta’ (Tamil for knife) and hence it also meant the players of ‘Sarpatta’ were as powerful as four knives. Also the fact that their logo happened to be ‘four knives’ further gave credence to this version.

Kitheri Muthu, a forgotten hero

When the British had left the country, Madras inherited two sports from them—cricket and boxing. While South Chennai (then Madras) took up the sport of cricket, North Chennai embraced boxing. A number of south Chennaites, prominently Brahmins, who played cricket, went on to represent India on the international stage. Some of the popular names include S Venkatraghavan, Krish Sreekanth, WV Raman, L Sivaramakrishnan, Sadagopan Ramesh, Murali Karthik, Dinesh Karthik, Ashwin Ravichandran, etc.

Unfortunately, boxers were never celebrated the same way despite their stunning performances. One such player was Manicka Mudaliyar Kitheri Muthu.

Born in 1901, Muthu was known to be an invincible boxer in the Sarpatta Parambarai. He first trained in silambam (stick fight) under his father Manicka Mudaliyar. Following a dispute in a silambam competition, Muthu eventually moved to train in Tamil Kuthu Sandai, in which a player would attack the opponent only on the face.

“From 1920 to 1960s, Muthu played only Tamil Kuthu Sandai. English boxing became popular only in the 40s. He lived in the fishing areas and did fishing-related work. Because of this many think he was a fisherman,” says Babu.

A 6-foot-tall Muthu with a muscular physique is said to be a lookalike of American boxer Sonny Liston. International boxer Gunboat Jack, who took on Muthu once in the ring, said the Indian pugilist’s punches were stronger than any he had ever faced.

During his time, Muthu was the champion of south India in professional boxing. Perumal Chettiar was his patron.

Besides Muthu, ‘Sarpatta Parambarai’ also had other great boxers such as ‘Gentleman’ K Sundarrajan, Manickam and his brother ‘Panakkaara’ Raju, Selvaraj, P Krishnan and his brother Durairaj and Ramadoss.

“Sundarrajan got the moniker ‘Gentleman’ because after attacking the opponent, he would withdraw to his corner and wait for his opponent to get up,” says Veeramani.

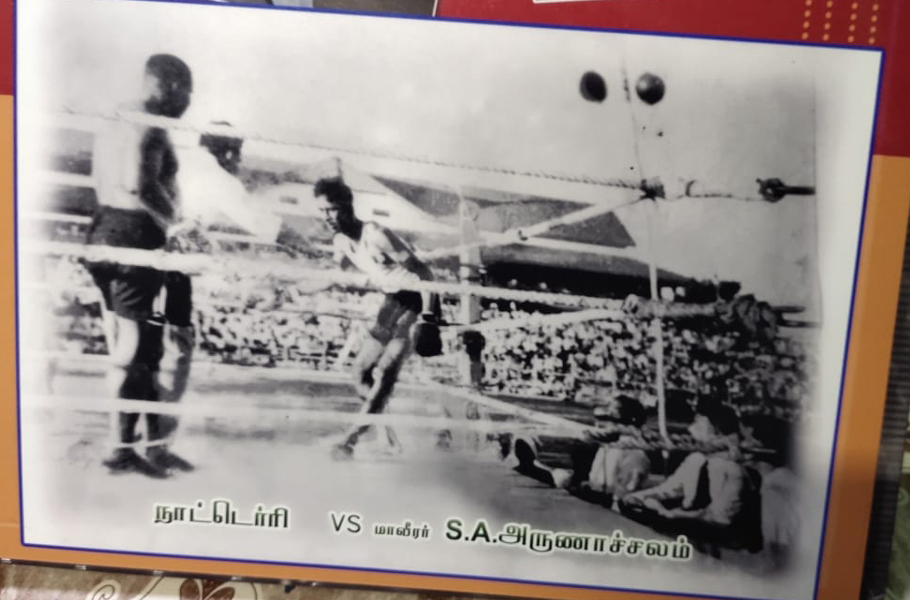

“Similarly, we had another top class fighter named Arunachalam. In a game between Arunachalam and the Anglo-Indian boxer, Nat Terry, the former lost his life inside the ring after being attacked by Terry. A couple of months later, Muthu beat Terry in a game. It was his best and most memorable game,” he says.

According to Veeramani, Muthu’s matches would go up to 6 rounds in Tamil Kuthu Sandai format while Sundarrajan would sometimes stretch till 10 rounds (in English boxing). Of course, that meant their opponents were equally good.

Boxing then and now

To understand the intensity of the bouts, one must know about how the game was played in those days. D Jagadish, a boxing coach and son of S Durai, a boxer with ‘Sarpatta Parambarai’, describes the difference between professional and amateur boxing.

“In those days, there were no rules in professional boxing. A player could hit the opponent anywhere in the body. There were no safety gears as well as different weight categories,” says Jagadish.

A player could fix a game with an opponent of his choice ahead of the game, so as to take revenge for earlier defeats. In fact, it was the ‘vaathiyaars’ (coaches) who would choose a player to confront an opponent. A student boxer had to wait for his turn even after many years of training, he says.

According to Veeramani, the glorious period of professional boxing came to an end in the 1970s, because of the lack of interest among the people. Along with the growing cinema culture, poverty and individual objectives, games like football and boxing slowly lost their sheen. And that put an end to all those Parambarais (lineages).

After the Parambarais were vanished, the descendants of some of the boxing giants launched their own clubs. Many of these clubs train students free of cost.

“Gone are the days when a person who trained in boxing would usually get a government job, especially in the railways, under the sports quota. Now, there is no support from the state government for these players. The state also has an Amateur Boxing Association, which is reeling under many problems because of which it has not conducted state-level matches for the past 3-4 years,” says Jagadish.

Many now come to learn boxing for self-defence and passion. When players don’t get government jobs, they turn into coaches by opening their own clubs, he says.

Babu says that if the government provides some land just to train the players, it would be more than enough.

“In order to carry forward the legacy of the boxers of yesteryear, their sons and grandsons opened boxing clubs and provided free coaching to anyone interested in the sport. We are providing training at Tiruvallur, Tondiarpet, Kasimedu and Mint. At each place, we have at least 20 students, including girls, on any given day. Since we don’t have a decent place to train, it becomes difficult especially on rainy days,” he says.

A boxing kit alone costs ₹40,000. Besides, a player needs to spend on his diet, coaching and fitness. Unless the government intervenes and helps with sponsorship, expecting a top class fighter or achieving a gold in Olympics will remain a distant dream, Jagadish says.

Politics and sports

Earlier, such matches were conducted mostly to earn money. Because of that the players would often clash even outside the rings. That was how many players turned into henchmen for politicians, says Jagadish.

Unlike in the film, wherein the protagonist claims his coach had defeated Nat Terry, Babu says it was his grandfather Kitheri Muthu, who defeated Terry and won a gold chain.

“Players like Muthu had their own fan following. During tournaments, these fans would place insane bets and tickets used to get sold like hot cakes. Political parties used these fans for their own benefit. That was how a lot of players like Sundarrajan and Vadivelu landed in politics and became assistants to politicians,” says Babu.

In his later days, Muthu lost interest in boxing. Although Muthu was a staunch supporter of Dravidar Kazhagam (DK) and its offshoot DMK, and had also been a bodyguard of Periyar, he never identified himself as a man of DK or DMK once inside in the ring.

Periyar was often greeted with rotten eggs and tomatoes in public meetings since he spoke about atheism and against superstition. It was Muthu who protected Periyar from all these attacks, says Babu.

“Interestingly, Muthu was given the title as ‘Dravida Veeran’ by Periyar (Dravidar Kazhagam founder) on August 8, 1943. In the same function, DMK founder CN Annadurai, praised Muthu and the news was carried in the publication ‘Dravida Nadu’ run by Annadurai,” says Veeramani.

It is this and many such anecdotes that made the boxers from North Chennai the kings of the ring.