- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How ‘Sher-e-Punjab’ Ranjit Singh built the Sikh empire

Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), popularly known as “Sher-e-Punjab” or “Lion of Punjab,” is traditionally celebrated for his exceptional leadership. He was at the forefront of the Sikh Empire, becoming its first maharaja (great king) in 1801, and he ruled it through the first half of the nineteenth century. The establishment of a stable and prosperous state in the northwest Indian...

Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), popularly known as “Sher-e-Punjab” or “Lion of Punjab,” is traditionally celebrated for his exceptional leadership. He was at the forefront of the Sikh Empire, becoming its first maharaja (great king) in 1801, and he ruled it through the first half of the nineteenth century. The establishment of a stable and prosperous state in the northwest Indian subcontinent by a native of the soil was a truly remarkable achievement, considering the consistent upheavals and the over 1,000 years of alien rule that this region had experienced. Maharaja Ranjit Singh was loved by his subjects, who were of diverse religions and ethnicities. He threaded them together as one, and they fought for him, creating a domain on par with any other major European power of that time.

Most of Ranjit Singh’s empire today lies in present-day Pakistan. I was able to recently visit his birthplace in Gujranwala, the forts, the battlegrounds, and two famous structures he built — Hazuri Bagh — where he held his court, and Ath Dara — a building with eight doors where he held his durbar (private gatherings). This was indeed an emotional and exhilarating experience. Visiting Sheesh Mahal, the palace of mirrors (which was his residence), and above it, his personal gurdwara (where he died), was equally incredible.

Ranjit Singh’s achievements leave us with awe and appreciation for a semi-literate boy who grew up quickly after losing his father at the age of twelve and became the undisputed ruler of the region. He had to swiftly adapt to protect his kingdom from the mighty British Empire, which eventually formulated a peace treaty with him. This left him as the only sovereign ruler in the Indian subcontinent that the British could not subjugate while he was alive. Let us take a closer look at his rise to power and his political career. Ranjit Singh fought his first battle alongside his father at age ten. After his father’s death, he became the leader of the Sukerchakia Misl and was proclaimed as the “Maharaja of Punjab” at age twenty-one. Ranjit Singh successfully absorbed the Sikh misls and took over other rulers to create the Sikh Empire. He formed alliances through marriages and friendships, a strategy that helped him in his early conquests. His mentor and guide in his earlier years was Sada Kaur, the head of the Kanhaiya Misl, who was a courageous and remarkable leader and who also happened to be his mother-in-law. On the invitation of the town elders and with her guidance at the age of nineteen, Ranjit Singh succeeded in taking over Lahore. Helped by Sada Kaur and by his friend Fateh Singh Ahluwalia of the Ahluwalia Misl, he captured Amritsar in 1802, becoming the undisputed leader of Punjab.

In 1807, Ranjit Singh’s forces attacked the Muslim-ruled Kasur and won it over from Afghan rulers. Ranjit Singh signed a treaty of friendship with the British in 1809 which demarcated the river Sutlej as the boundary between their domains. He conquered the city of Multan in 1818, and the whole Bari Doab (the area between the Ravi and Beas rivers) came under his rule. In 1819, he successfully defeated the Afghan Muslim rulers and annexed the Srinagar and Kashmir regions, stretching his rule into the north and the Jhelum valley, beyond the foothills of the Himalayas. In May 1834, Dost Mohammed of Afghanistan accepted the sovereignty of the Maharaja over Peshawar.

Ranjit Singh referred to his reign as “Sarkar Khalsa” (Empire of the Khalsa), and called his court “Darbar Khalsa” (Court of the Khalsa). He dressed simply, did not wear a crown (his turban was his crown), or sit on a throne. He did not get coins minted in his name but in the name of the gurus. He ruled as a representative of the Khalsa to serve his people. He showed great consideration and kindness to fallen foes, giving them a jagir (land grant) each as a source of income so they could live comfortably. As Patwant Singh and Jyoti Rai have noted, Ranjit Singh “drew his strength not from the brutal exercise of power but from his humanity, vision, vitality and tolerance… The powerful impulse that drove Ranjit Singh to create a just, secular and cosmopolitan society for his people was his unshakeable faith in the religion into which he was born.” In the words of Henry Prinsep, “in action he has always shown himself personally brave, and collected, but his plans betray no boldness or adventurous hazard.”

Ranjit Singh created an army which was led by able generals and was Westernized over time. Before 1822, most of the state conquests were led by men like Mokham Chand, Hari Singh Nalwa, and Misr Dewan Chand. Nalwa has been recognized as one of the greatest military commanders of his time and was involved in most of the invasions. Nalwa, in addition, was an able administrator and governed first Kashmir and later Hazara and Peshawar, which were tumultuous regions and brought stability to them. According to Vanit Nalwa, he acquired the name Nalwa (tiger) because “by the age of fifteen, fully armed he wrestled a tiger to its death” — a truly remarkable feat.

Many dangerous missions were also led by Akali Phoola Singh, the leader of the Akalis (the immortals), whom he used as cavalry. Commenting on the Khalsa soldiers, Joseph Davy Cunnigham, an official of the East India Company, wrote that “the Sikh owes his experience as a soldier, to his own hardihood of character, to that spirit of adaptation which distinguishes every new people, and to that feeling of a common interest and destiny implanted in him by his great teachers.”

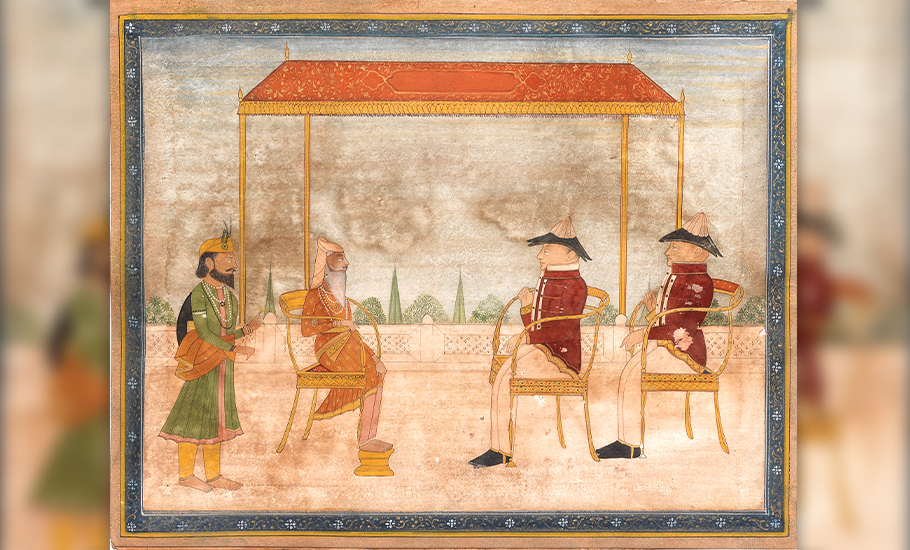

It is believed that approximately forty-two foreign officers over time were attached to the Khalsa army, including men of French, Italian, German, American, and Spanish origins as well as veterans from Napoleon’s army. For instance, Jean François Allard arrived in Lahore in 1822 and rose to be a general in Ranjit Singh’s cavalry. Likewise, Paolo Avitabile and Auguste Court joined Ranjit Singh’s army in 1826 and 1827, respectively. Both soon became high-ranking officers who served with distinction and were also involved in extensive training of the troops. American Colonel Alexander Gardner also joined the army in 1832.

A royal army, the Fauj-i-Khas, was created. It contained cavalry, infantry, and gunnery units and it became known as “the French Legion.” Along with this, the Fauj-i-Ain, a regular army, was established. It numbered nearly 70,000 in strength with infantry, cavalry, and artillery, as well as traditional soldiers. The artillery was organized into lighter guns pulled by horses, light swivel guns mounted on camels, and heavier guns pulled by bullock carts. The army included Sikh, Muslim, and Hindu soldiers. General Ventura, who had arrived in Lahore in 1822, trained battalions of infantry, while General Allard trained the cavalry. Punjabi generals Ilahi Bakhsh and Lehna Singh Majithia oversaw the training, command, storage, and supply of the artillery.

Lehna Singh Majithia was one of the ablest administrators in Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s court. However, his capability as an administrator was overshadowed by his talent in astronomy, architecture, mathematics, and literature. He, along with General Court, was responsible for the establishment of a cannon foundry in Lahore, which proved to be at par with, if not better than, any other foundry in the world.

Multiple forts were built, especially under Nalwa, on the border with Afghanistan. Describing the reconstruction of Govindghur Fort in Amritsar, William Lewis M’Gregor wrote that,

in it the treasure was deposited, under a guard of 2,000 soldiers, and put under the charge of Emamoodeen… This is the celebrated fort of Govindghur, strongly built of brick and lime, with numerous bastions, and strong iron gates: twenty-five pieces of cannon were likewise placed in the fort.

Sikhs in Ranjit Singh’s empire were 10-15 percent of the total population of 5,350,000. Writing about Ranjit Singh, Hari Ram Gupta has stated that “the love for his subjects was enshrined in his heart” and that “he ruled with unprecedented liberality and never caused bloodshed in the name of religion.” Fakir Syed Waheeduddin also wrote about a sense of prosperity and security under Ranjit Singh’s rule: “Punishments were humane. For example, there was practically no capital punishment.”

The posts in civil and military administration were held by people from all religions. Prominent amongst them were the Fakir brothers and Dogra brothers (Dhian Singh, the longest-serving prime minister of the Sikh Empire, was one of them). Grants were given to all religions especially on their holy occasions. Agriculture was the mainstay of the empire’s economy with two thirds of the population made up of peasants. The production of Kashmir shawls was encouraged, and these beautiful garments were frequently given as gifts.

Punjabis have traditionally yearned for education and showed great reverence for teachers. Both boys and girls attended primary school, and the literacy rate was quite high. Commenting on Ranjit Singh’s policies pertaining to education, Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner noted that “his great aim is to destroy the monopoly of learning, and of the social or religious ascendancy of one class, and to make education the property of the masses of the community.” Funding for schooling came not only from the local community, but also from royal families and the state treasury. The policy of distributing grants to educational centers affiliated with various faiths led to a high level of literacy even amongst the rural populace. Fakir Nur-uddin, the minister of education, compiled a primer entitled Noor (Light) that helped one learn basic alphabets, elementary writing in important local languages, and mathematics. Traditional and indigenous education flourished, thus contributing to the spread of knowledge and improvement of learning across the social spectrum.

In this golden age of stability, art, architecture, and culture prospered in a secular environment, after decades of uncertainty and anarchy. There was renewed construction of beautiful residences, palaces, religious monuments, along with the laying down of gardens. Amritsar and Lahore became cosmopolitan cities with traders and influences from Central Asia, France, Britain, Persia, Afghanistan, and Russia. Indigenous industries were revived, and vocational craft schools were opened across the empire where painting, calligraphy, sketching, and drafting were taught. Amritsar, Lahore, Srinagar and other cities were major centres for such activities.

(Courtesy of Roli Books)

Parvinderjit Singh Khanuja, a medical oncologist, was born in Muzaffarnagar. Besides practising medicine, he is involved with multiple non-profit organisations and is a member of the Board of Trustees of the Phoenix Art Museum, where he contributed to the creation of a permanent Sikh art gallery.