- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

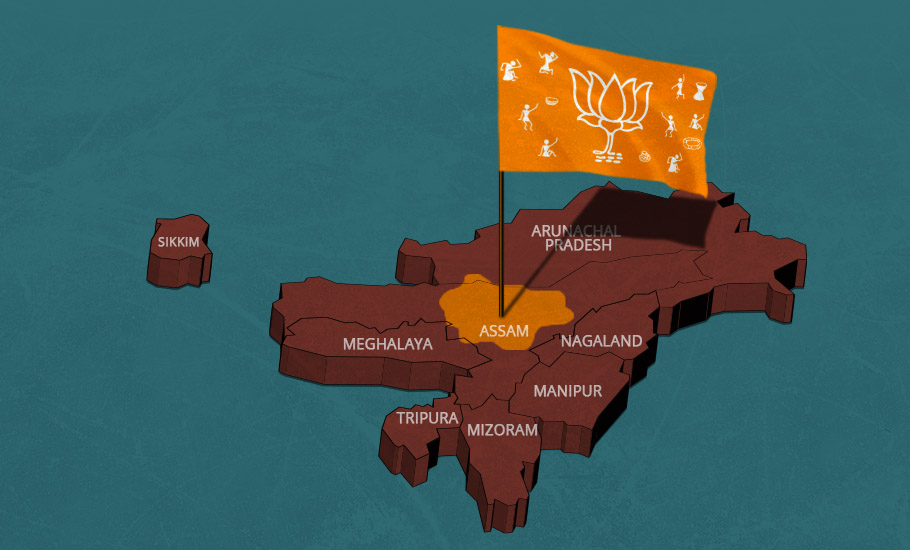

BJP's mission Northeast: How it started vs where it's going

The rise of the BJP in the Northeast in recent times has intrigued many, considering the region is home to more than 200 communities of India.

Modi is a “terrorist” and “blood of Muslims flows through water pipes in Gujarat”—Himanta Biswa Sarma, 2014 How enormously blessed I feel Hon PM Sri @narendramodi for your faith in me.—Himanta Biswa Sarma, 2021 If you are a social media regular, you are probably familiar with the numerous memes of “how it started…how it ended”. The idea is to show the passage of time in...

Modi is a “terrorist” and “blood of Muslims flows through water pipes in Gujarat”—Himanta Biswa Sarma, 2014

How enormously blessed I feel Hon PM Sri @narendramodi for your faith in me.—Himanta Biswa Sarma, 2021

If you are a social media regular, you are probably familiar with the numerous memes of “how it started…how it ended”. The idea is to show the passage of time in a particular journey, similar to the before-and-after format, ending with a twist—sometimes the end result being completely different from the initial goal.

Newly anointed Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma’s political journey could be summed up in a similar meme, just that all this is far from a funny internet trend for a region which seems to be fast shifting its goal post from enthnic nationalism to Hindutva-centric politics.

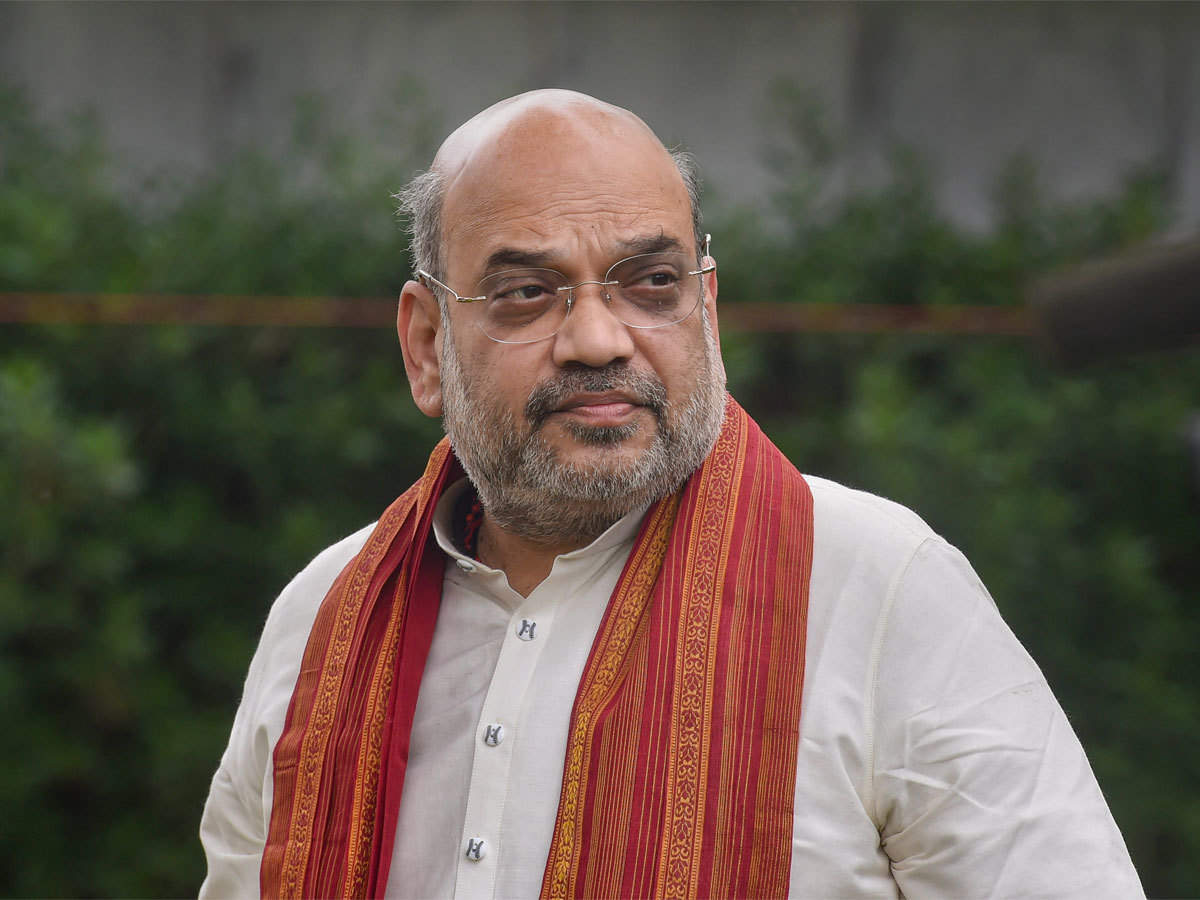

While much water has flown down the Brahmaputra since the days of Sarma as a Congress minister to him becoming Modi-Shah’s biggest asset in the Northeast, the BJP’s mission Assam too has undergone many tweaks and tricks. It has finally arrived at a juncture where the party has managed to install a government in the state which is all things Hindutva—love jihad, land jihad, cow protection bill, population policy etc.

The hijacking

The Northeast is perhaps India’s most diverse region being home to over 200 of the 635 tribal groups in the country. What makes the region more varied is that the diversity is not limited to ethnicity.

Multiple religious denominations such as Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, animism, indegenous faiths and even Judaism and Sikhism are followed by different communities of the region.

Considering this multifariousness, the recent ascendency of the BJP in the region appears intriguing, at least on the face of it. The resounding victory in Assam assembly elections and the recent induction of five parliamentarians from the region in the Union council of ministers have left political pundits raving over Team Modi’s actualisation of BJP’s mission Northeast.

For a region that for long has endured mainstream alienation, the move seems to be the much-needed emotional connect. But is it? After all, the concept that drives the BJP—a unitary Hindu rashtra (country) based on cultural-religious homogeneity—is at odds with the region’s diversity and pronounced desire for a greater autonomy, something that has been clearly demonstrated by various insurgency movements as well as popular protests.

So, many may be tempted to dismiss the BJP’s rise as an artificial growth or a post-2014 phenomenon, especially since most states in the region have a tendency to veer towards the party ruling at the Centre.

Such arguments are not entirely unfounded, though.

The first-ever BJP government in the land-locked region was formed in Arunachal Pradesh way back in 2003 during the reign of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government at the Centre headed by Atal Bihari Vajpayee.

A few months after Gegong Apang led his party—the Arunachal Congress that he had formed after splitting the Congress—to an electoral victory, he merged his entire party with the BJP to give the saffron brigade its first taste of power in the Northeast.

Apang, however, returned to the Congress with lock, stock, and barrel immediately after the party came back to power at the Centre in 2004.

But that was nearly two decades ago. At present, the BJP enjoys much greater and wider support in the Northeast—that sends 25 members to Lok Sabha and 14 to Rajya Sabha—than what it had during the Vajpayee era. (The party is heading governments in Arunachal, Assam, Manipur and Tripura while its alliance partners are ruling Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Sikkim.)

Hindutva’s new laboratory

Unlike the Vajpayee era, the party now appears more determined to work on a definite plan to sustain its growth, converting the region into a laboratory of its new formula—blending Hindutva with the region’s ethnic aspirations and grievances.

“The BJP has cleverly aligned its Hindutva agenda with the region’s sense of neglect and fear of losing identity to create a durable political base,” says Habung Payeng, a former information commissioner of Arunachal Pradesh.

A constant narrative in the region since Independence is that it is being swamped by illegal migrants from Bangladesh and that New Delhi is not doing enough to protect it.

The partition of India in 1947 had a serious demographic consequence in the Northeast due to large-scale migration of people from the erstwhile East Pakistan (Bangladesh) to the region.

The influx totally changed the demographic profile of the tiny state of Tripura, where the percentage of tribal population came down from 53.16 per cent in 1941 to 37.23 per cent in 1951, turning it into a Bengali-majority state.

This created a sense of insecurity among other northeastern states, particularly Assam that had to accommodate a massive influx of refugees from across the border.

This constant fear of being swamped by Bengali migrants sparked the anti-foreigner movement in Assam in 1979 which spilled over to other neighbouring states.

But until the rise of the BJP in the state, the fear of migrants had no pronounced religious undertones. It was largely contested as an ethnic issue.

The BJP, however, has turned it into a full-fledged communal issue claiming that the Hindu migrants need to be treated as persecuted refugees whereas the Muslims are illegal migrants who should be deported back to Bangladesh.

According to citizen rights activist Hasina Ahmed here is a reason why the saffron party found it easier to sell and repackage Hindutva in Assam—something it has so far failed to do in southern states like Tamil Nadu and Kerala.

“The Assamese angst against Bangladeshi migrants somehow centered largely around the fear of losing their land to ‘miyas’ since most of the land cultivators brought by the British were Bengali Muslims. But such sentiments were not pronounced. So, it became easier for the BJP to add religious colours to Assamese nationalism,” she says.

The inherent parochialism at the heart of the anti-foreigner discourse of the 1980s further helped the BJP to drill its ‘Hindu khatre Mein Hai’ (Hindus are in danger) narrative deeper into the Assamese consciousness post-2014, she adds.

The saffron party first positioned itself as the champion of the region’s cause, blaming the alleged indifferent attitude of the Congress for the lack of attention and development of the Northeast. It promised to undo the ‘wrongs’, generating lots of hopes and expectations.

“However, the seven years of the BJP rule at the Centre has not just failed to resolve the migrant conundrum but also to live up to its promises of development and growth in the region,” says Pradesh Congress general secretary Apurba Kumar Bhattacharjee.

While the unemployment rate continues to be very high in most of the states across the region, no major investment has come to the Northeast, he adds. Also, apart from rechristening the Look East policy to Act East, the initiative has not seen any progress.

The litany of complaints is long. “What happened to the much-publicised peace talks with major insurgent groups? The government has failed to make any headway. Even the fencing work on the India-Bangladesh border initiated by the previous Congress-led government has not seen much progress despite the BJP constantly making alleged infiltration from Bangladesh a political issue.”

Master Bluster

When it comes to allocation of funds to the region, Bhattacharjee points out, the BJP failed to retain the hype it had created by assigning a whopping Rs 53, 706 crore in the 2014-15 budget presented immediately after Modi took over as prime minister. It was a significant spike from the budgetary allocation of Rs 31,625 crore in the previous fiscal.

But in the next fiscal (2015-16), the allocation dropped to Rs 29, 087.93 crore. In 2016-17, Rs 33,097 was set aside for the region.

It took a pandemic and elections in Assam for the BJP government to surpass the allocation it made in 2014-15 seven years later. In the 2021-22, the budget allocation for the north-eastern states has increased to Rs 55,820 crore. A significant chunk of the enhanced allocation was earmarked for poll-bound Assam.

Again, the much-hyped Development of North Eastern Region (DoNER) ministry, established in 2001 for the socio-economic development of the region, and the North East Council (NEC), an advisory body formed in 1972, too failed to flourish under the present government.

Expressing his discontentment with the functioning of the NEC, Arunachal Pradesh Chief Minister Pema Khandu (of the BJP) recently stated that “nothing concrete” was coming out of the agency.

It is this and many such big and small instances that seem to have convinced Bijit Mahanta, a former student leader of Assam, that the BJP is “all talk, no substance”.

“For the past seven years, it has not done anything substantial for the region, other than distorting history and creating division among people,” says Mahanta.

The former student leader points out how the BJP in its attempt to mainstream the regional heroes of Northeast depicts them as Hindu crusaders just to suit its agenda.

Ahom general Lachit Borphukan, who defeated Mughals in the Battle of Saraighat in 1671, is invoked by the BJP as a Hindu warrior who averted the ‘Islamic invasion’, equating Mughals with Muslims.

“The BJP conveniently forget that in the battle a Muslim named Ismail Siddique, popularly known as Bagh Hazarika, was the Ahom army’s navy general. The Mughal army was led by Kachwaha king, Raja Ramsingh I, a Rajput Hindu and not a Muslim.”

The Hindu-Muslim binary is important for the BJP to channelize the region’s fear over identity loss to make Muslims, particularly of Bengali origin, a perennial suspect responsible for all the problems inflicting the region, he adds.

Hindu, Hindi, Hindutva

Political observers keeping a close eye on the developments in Assam are quick to point to the government’s urgency behind pushing certain plans—a two-child policy for availing government benefits; eviction drives to free land ‘belonging’ to temples, satras and reserved forests from alleged encroachers; the proposed cattle protection law, or the proposed Assam marriage bill to check ‘love Jihad’ of all kinds.

“All these are aimed at pushing the same old narrative that the BJP successfully peddled in the Hindi heartland,” says Shahjahan Talukdar, a Guwahati-based social activist and publisher of Assamese daily Dainik Gana Adhikar.

The Assam government’s new-found enthusiasm displayed in decisions like changing the term ‘Gaon Burha’ (village headman) to ‘Gaon Pradhan’ has also not gone unnoticed.

The Hindutva push, many say, has elbowed out the region’s core issue of protecting its distinct identity and culture, greater economic development of the region and judicious use of its resources for the greater benefit of the region.

“The Himanta Biswa Sarma-led BJP government in Assam has surrendered Assamese identity to the ideology of RSS-BJP,” peasant leader and MLA Akhil Gogoi alleged pointing at the recent developments.

But is the cow-belt politics sustainable in the long run in a multicultural land known for its fascination with pork and beef meat?

Chinks in the armour

Much to the BJP’s worry, its formula already appears to be losing its utility in Manipur and Tripura, two of the four states where it is heading a government.

In both these states, the BJP is besieged by internal bickering as well as issues of non performance. The challenge is tougher for the party in Manipur as the state will go to the polls early next year.

To mitigate the crises, the BJP did what it does better—playing to the gallery with the induction of five ministers in the Modi ministry billed as a game-changer for the region. But the highest-ever representation to the region in the Union government, is more out of a political exigency than any real concern for the region as the BJP spin doctors would like the people to believe.

Former Assam Chief Minister Sarbananda Sonowal needed to be rehabilitated after he was unceremoniously removed from the chief ministership even after leading the party into an electoral victory.

The two other new entrants from the region in the ministry Dr Rajkumar Ranjan Singh of Manipur and Pratima Bhoumik of Tripura on the other hand got the berth to woo the states where all is not well for the BJP.

Such posturing aside, the ground realities speak of a status quo in terms of the developmental goals and resolving of various conflicts that continue to simmer.

For instance, the recent escalation of border conflicts among Assam and its contiguous states, including the controversy over the Border Roads Organisation’s ‘renaming’ of a town in Arunachal Pradesh and showing it as part of Assam during a programme attended by Defence Minister Rajnath Singh has rubbed various organisations in the frontier state the wrong way.

These flare-ups, even though they failed to make national headlines, go on to prove that Northeast is not a homogeneous entity but a region that shares similar culture with contesting identities and ethnic aspirations.

“To lump the Northeastern states together as one entity, ignoring the diversity, is not enough to maintain the iron grip,” adds Mahanta.

Pushing the ‘one nation, one religion’ potion down the throats, he fears, will only create more divisions.