- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Between faith and fraud: Why Islamic banking is back in focus

Until two years ago, Mahaboob Shaik (name changed) owned a garment factory that employed 53 people. But the government’s shock banknote ban in November 2016 and the July 2017 implementation of the Goods and Services Tax wrecked his business. In late 2017, Shaik shut his factory in Bengaluru’s Peenya industrial area and laid off all the workers. Then, he took a leap of faith. Now,...

Until two years ago, Mahaboob Shaik (name changed) owned a garment factory that employed 53 people. But the government’s shock banknote ban in November 2016 and the July 2017 implementation of the Goods and Services Tax wrecked his business. In late 2017, Shaik shut his factory in Bengaluru’s Peenya industrial area and laid off all the workers. Then, he took a leap of faith.

Now, the 36-year-old is teetering on the brink again.

After shutting the factory, Shaik invested ₹20 lakh in Bengaluru-based I Monetary Advisory (IMA). The non-banking finance firm founded in 2006 claimed to offer so-called ‘halal’ investments or financial products compliant with the Islamic law of Shariah. “I was sceptical to invest at first, so both my wife and I initially invested ₹1 one lakh each. After getting the promised returns for three months, we invested ₹5 lakh each again, and further put in another ₹8 lakh after six months,” Shaik says.

Earlier this month, IMA went bust, leaving Shaik and thousands of other investors angry and scarred.

Not a one-off instance

IMA wooed investors, mainly Muslims, by making two promises: high returns and investment compliance based on Shariah. The Shariah bars people from charging interest on loans or receiving ‘riba’ or making exploitive gains on investments. So, the IMA promised to make investors partners and share the profits. It floated various schemes and offered exorbitant returns of 3 per cent per month (36 per cent annually). For perspective, commercial banks generally offer 6-8 per cent annual returns on fixed deposits.

Over the past week, close to 20,000 people have registered complaints with the police. They had invested anywhere between ₹50,000 and ₹20 lakh. The company reportedly raised more than ₹2,000 crore. Considering the severity of the case, Karnataka Chief Minister HD Kumaraswamy ordered a special investigation team (SIT) to probe into the scam. The team arrested seven directors and the company’s auditor but declared that the founder Mohammed Mansoor Khan, who faked his suicide, fled to Dubai.

This, however, is not a one-off instance where the Muslim community felt cheated. Companies like Morgenall, Heera Gold, Ambident Marketing, Ajmera Group, Burraqh Group, Aala Ventures among others have cheated thousands of investors in recent years. Most of them claimed to operate as Shariah-compliant businesses to attract the Muslim community, who kept away from the mainstream banking services due to their religious beliefs.

Social activist and All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen Shahbaz Ahmad Khan, who raised an alarm over Ponzi operations of Heera Gold led by Nowhera Shaikh, says, he complained to the police and probe agencies about IMA much before the scam came to light.

“There’s nothing ‘halal’ about these investments. There business activities are full of ‘haram’. They act in connivance with the Police, bureaucrat and the prominent maulanas (Muslim scholars), who endorse such products for their own benefit,” Khan says.

Why Islamic banking

Islamic banking, formalised in the late 1970s to comply with the Shariah, forbids taking interest on loans. As a result, it follows the principle of profit and loss sharing with the beneficiary.

So, how do such banks make money? Well, instead of interest income on loans, Islamic banks buy goods and properties (house, car, gold) for clients, and then sell them back at a profit. They also engage in lease and hire purchases but avoid gambling or investing in liquor, tobacco and weapons.

In other words, while conventional financial intermediation is largely debt-based and allows the transfer of risk, Islamic finance is asset-based and centres on sharing the risk.

In fact, this approach may have even helped contain the impact of the global financial meltdown in 2008, according to an International Monetary Fund report. The IMF said that smaller portfolios, lower leverage and adherence to Shariah principles — which bars financing or investing in the kind of instruments that hurt conventional banks — helped contain the impact of the crisis.

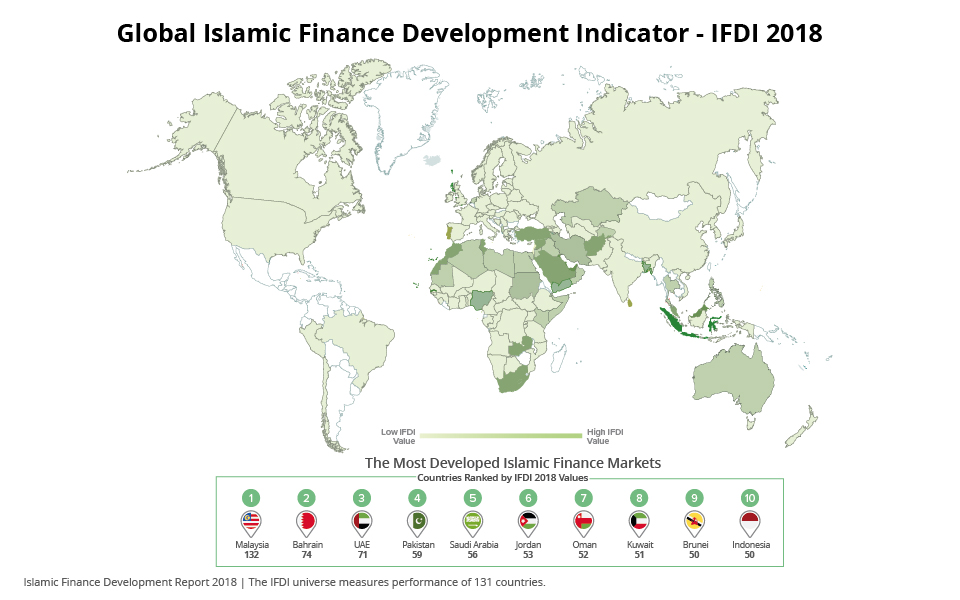

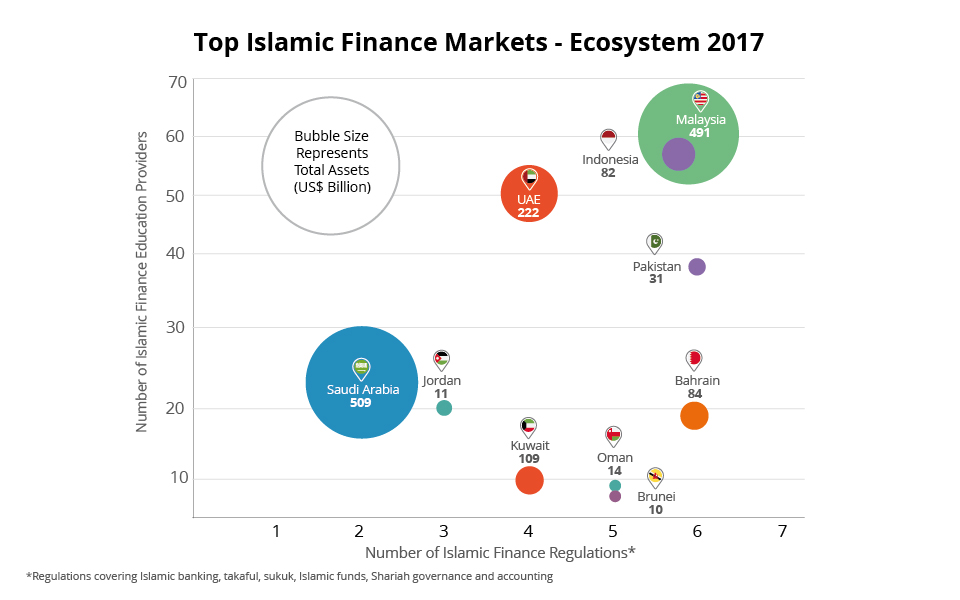

The Islamic finance system has grown over the past few decades into a behemoth that attracts investors across faiths. The industry’s assets grew at an annualized pace of 6 per cent from 2012 to $2.44 trillion in 2017, according to the Thomson Reuters’ Islamic finance development report, 2018.

The first successful example of an Islamic bank was Malaysia’s Tabung Haji, which came into existence due to demand for interest-free money for the Haj pilgrimage. It started in 1963 with a total of 1,281 prospective pilgrims as investors. Ever since, the country has become a leading Islamic finance market. Today, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Malaysia together contribute nearly 65 per cent of the total industry.

In India, too, some private firms have adopted Shariah rules to provide credit and investment options to Muslims.

Islamic banking in India

‘Halal’ (lawful or permitted) banking (based on the practical applications of Islamic economics) is legalised in several countries, including non-Muslim dominant ones such as the US, the UK, Sri Lanka and Japan. But it faces challenges in India. This, despite the fact that the country is home to 172 million Muslims (2011 Census) — the third-largest Muslim population in the world after Indonesia and Pakistan.

With the unveiling of the latest scam, many believe the debate over legalisation of Islamic banking in India gains significance. A lack of regulatory framework, absence of corporate governance and poor investor awareness in India lead to such financial crimes. Without a legal framework in place, firms like the IMA find it easier to operate.

According to Shariq Nisar, professor at Rizvi Institute of Management Studies and Research, Mumbai, Islamic banking is gaining recognition globally — not just with Muslim-majority countries — and it is time for India to catch up.

“Financially illiterate investors either go for gold or real estate investments. With the absence of regulations, some financial firms tend to exploit and cheat people. That’s a reflection of what’s happening in places like Bengaluru and Hyderabad,” Nisar says. He adds that people across segments, from low-income groups to the middle class and rich investors, go for ‘halal’ investment schemes.

With an increasing number of commercial banks around the world offering interest-free financial products, even non-Muslims invest in such banks. The UK is a great example, Nisar adds.

Even in India, there are Shariah-compliant businesses and indices on the Bombay Stock Exchange and the National Stock Exchange. A few private banks offer Shariah-compliant mutual funds as well.

RBI’s stands

With numerous scams coming to light, the debate on legalising the Islamic banking system to channelise the Muslim investment fund arose in the Indian banking domain. Representatives of the Indian Muslim community have been pushing for such banking products.

Back in 2008, a Reserve Bank of India committee on financial sector reforms headed by Raghuram Rajan mooted the idea of Islamic banking in 2008. The committee stressed on the need for a closer look at the issue of interest-free banking in the country.

After analysing the use of formal cash loans by Muslim households, the committee concluded that Muslims were less inclined to access formal finance, in general, although they might be accessing long-term formal finance (Shariah compliant).

“The non-availability of interest-free banking products (where the return to the investor is tied to the bearing of risk, in accordance with the principles of that faith) results in some Indians, including those in the economically disadvantaged strata of society, not being able to access banking products and services due to reasons of faith. This non-availability also denies India access to substantial sources of savings from other countries in the region,” the RBI report said.

While Rajan went on to become the RBI governor in 2013, his predecessor D Subbarao had a different view. Subbarao, in 2012, said that the current Banking Regulations Act does not permit Islamic banking because interest rate was an important component of the banking system.

“We do not permit banks to take risk positions in business if they finance. Government asked us and we have written to them that should they intend to carry forward Islamic banking, they have got to have a new law for this and I believe that it is under the examination of the government,” Subbarao had said.

In 2017, the RBI struck down a proposal to allow Islamic finance and said the decision was taken after considering the wider and equal opportunities available to all citizens to access banking and financial services.

However, in the same year, the CPI(M) government in Kerala opened an Islamic cooperative bank. About 22 minority cultural coordination committees supported the move.

Political twist

In 2011, the Kerala government sanctioned a NBFC service by the State Industrial Development Corporation (KSIDC) based on Islamic principles. However, BJP Rajya Sabha MP Subramaniam Swamy had argued that the setting up of a financial service company (based on Shariah) with government participation went against secular principles and filed a writ petition in the high court. The court dismissed the petition saying it could not be treated as promoting a religion.

In 2018, the then Minister of State in the Ministry of Finance Shiv Pratap Shukla told the Lok Sabha that the government did not pursue the matter taking into account opportunities available to access financial services and legal challenges involved in introducing Islamic banking products.

The BJP was of the view that the government had already introduced other means of financial inclusion like Jan Dhan Yojana and Suraksha Bima Yojna for all citizens.

Loot of poor people

“What happened in Bengaluru was nothing but organised looting. We need regulatory bodies like SEBI and the RBI, along with the Companies Act, to govern these businesses. We cannot have maulana-run banking businesses,” says Zafar Sareshwala, chief executive and managing director of Ahmedabad-based Parsoli Corp, which offers Shariah-compliant portfolios. Sareshwala was the former chancellor of Maulana Azad Urdu National University. “We need the best fund managers and industry domain experts to oversee these transactions.”

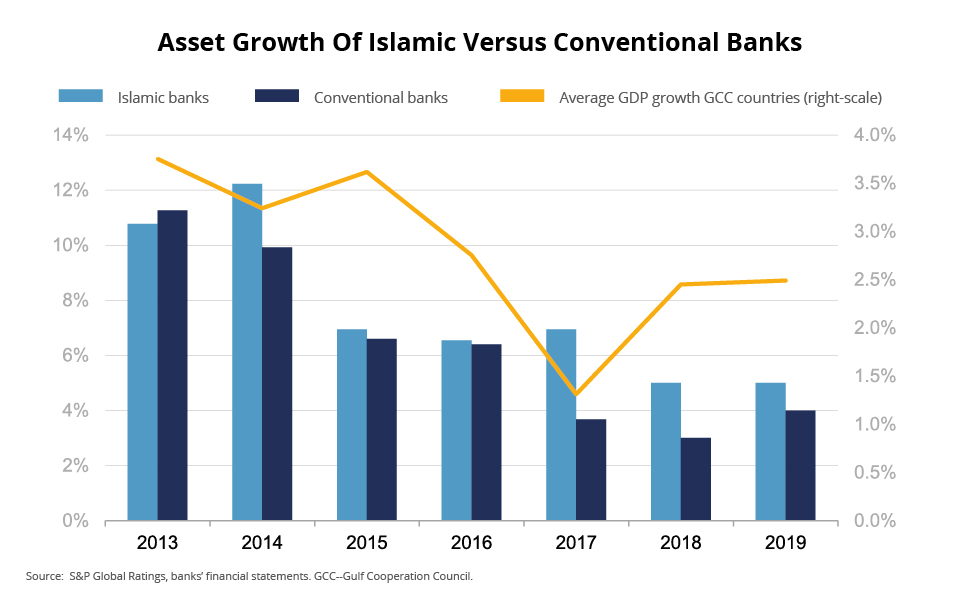

In fact, according to S&P Global Islamic Finance Outlook, 2019, the financial performance (assets growth) of Islamic banks globally displayed strong improvement compared to conventional banks. Professor Nisar feels while a legal framework around Islamic banking may not eliminate financial frauds taking place in the name of religion, it could contain such scams to a great extent.