- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

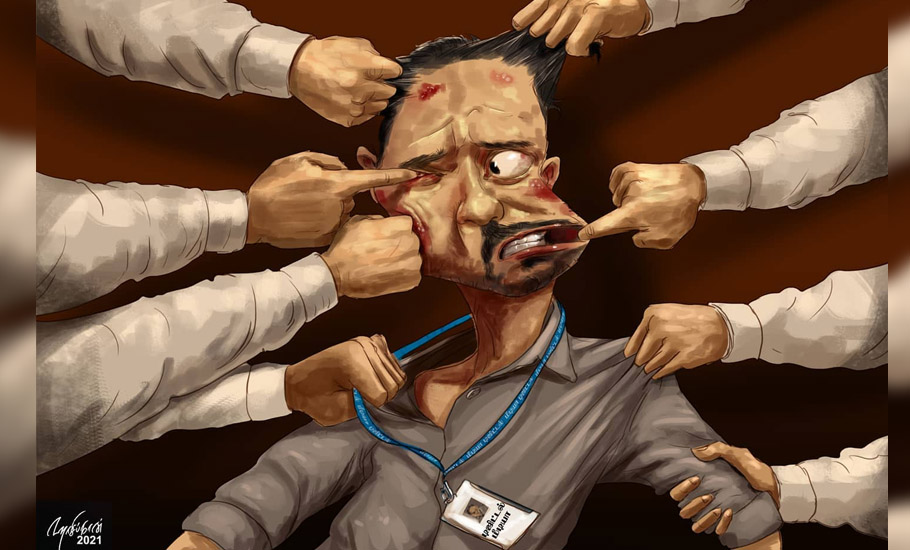

Being a cartoonist in ‘too much democracy’ -- hear it from Hasif Khan

In the heat and dust of the election season, how does the big picture look? Well, Adura Rama, Adura… (Dance Rama, dance). This is how 39-year-old Chennai-based cartoonist Hasif Khan sees the upcoming Assembly elections, where the ‘monkeys’ within the state are forced to dance to the tunes of the big brother from the Centre (in the present context — the saffron power). In...

In the heat and dust of the election season, how does the big picture look? Well, Adura Rama, Adura… (Dance Rama, dance). This is how 39-year-old Chennai-based cartoonist Hasif Khan sees the upcoming Assembly elections, where the ‘monkeys’ within the state are forced to dance to the tunes of the big brother from the Centre (in the present context — the saffron power).

In other words, the narrative is set by the overall political environment in the country. The alliances among various parties further add to the cacophony.

Amid all this, Hasif, through his cartoons and illustrations, tries to make us read between the lines. For instance, his digital image (below) illustrates how the magical freebies pulled out of the politician’s hat is actually snatched from the common man’s pockets.

It’s not that the voters don’t see the magic trick, yet they get tricked. Well, it’s called a trick for a reason!

If cartoonists play a huge role worldwide in forming public opinion, of late, Hasif and others like him often find themselves facing the government’s ire.

In an India of “too much democracy”, there have been too many instances in the recent past that shows neither freedom (for all kinds of satirists and social critics) nor tolerance on part of those being called out or mocked at.

How the world looks from down there

Hasif, of course, is not new to this game. Very early on in his journey, he created ripples with a cartoon of former CM J Jayalalithaa in 2011. The AIADMK supremo had just resumed office for the third time and was reluctant to give a go-ahead to the ‘Samacheer Kalvi’ (uniform education) scheme.

Ananda Vikatan, leading Tamil weekly, published an article lampooning Jayalalithaa over the issue. But it was an illustration accompanying the article that made Hasif a household name in Tamil Nadu. It showed Jayalalithaa sitting on a pile of books.

“The artwork added fuel to an already burning issue,” says journalist-author Kavin Malar.

Malar explains the local context. The cartoon was every bit provocative since books are considered absolutely sacred in Tamil culture, like most other parts. “If someone inadvertently happens to drop a book, they immediately pick it up, touch it to their forehead and kiss it as a mark of apology. When people saw Jayalalithaa in that cartoon sitting on books, it was obviously seen as a huge mark of disrespect to goddess Saraswati (Goddess of knowledge and wisdom). People were incensed.”

Many in the state turned against the artist. Many others understood the message he was trying to convey. With that, Hasif had truly arrived.

Kanyakumari to cartoon world

Hasif’s childhood was unremarkable and every bit ordinary spent mostly in a small Kanyakumari village, Eraviputhoor Kadai.

“I never went to an art school. All that I do now is something that I learnt on my own,” says Hasif, whose father owns a small tea shop and mother is a homemaker.

Growing up with two more siblings, Hasif says he loved doodling as a child.

“I used to draw a lot from my school days. When I was in Class 8, I started reading magazines and the ‘Ananda Vikatan‘ in particular appealed a lot to me. The cartoons of Madan, paintings of Maniam Selvan, Jayaraj, Shyam inspired me even more.”

Then there were artists in his village such as Nasar and Marthandam Rajasekaran, who used to draw signboards and banners. “Rajasekaran’s paintings during ‘Kalai Iravu’ (art night) conducted by the Tamil Nadu Progressive Writers and Artists Association, a cultural arm of CPM, were quite eye-catching. I used to replicate those artworks. This is how I learned the trade.”

Other than painting at home, Hasif never participated in any competitions. When he was doing his graduation in Computer Science at Annai Velankanni College, he participated in a painting competition once.

“My painting got the first prize. That was the first time my artwork was recognised in public,” Hasif says with a child-like joy.

After college, he moved to Kerala where he worked in an animation company.

“There, I learnt 2D and 3D animations. I worked in the animation industry for 10 years that helped me further hone my skills. In between, I also worked in Dubai.”

Finally, a staff cartoonist

In 2010, Hasif moved to Chennai and started working with an advertising company along with his friends. Although he claims he was happy with what he was doing, deep within he knew his true calling in life.

“In 2011, after Jayalalithaa came to power, I drew a caricature of her and e-mailed it to Vikatan. I had given no other details. Within a couple of days, I got a call from the media house. They commissioned me to make an illustration for an article.”

That’s how his journey with the media group started.

After the rave reviews as well as the brickbats that the ‘Samacheer Kalvi’ cartoon got, Vikatan gave him a platform to explore his ideas. Titled ‘Galatoon’, the cartoons published in the last page of Ananda Vikatan every week became a rage among the readers.

Ra Kannan, former editor of the magazine who is known for spotting some great talents, says Hasif is a man of few words and it’s great that he chose cartoons to express his emotions.

“Generally, cartoons are mostly created with freehand line drawings. But Hasif uses digital technology and colours too. That added more weight to the issues and his vivid imagination. He is an artist who understands the feelings and problems of the common man.”

Sometimes with a single stroke, he is able to say a lot of things, Kannan adds.

Kannan again is a veteran in dealing with miffed governments and curbs. During his editorship till 2017, the magazine was slapped with 38 cases. While half of them were filed because of various articles, the accompanying cartoons attracted the rest of the legal suits.

Yet, he is modest enough to underplay his role in holding aloft the flag of freedom of expression.

“It doesn’t mean I gave him [Hasif] the freedom. Anger and dissatisfaction against governments are expressed by some in the form of poems, essays and photographs. Hasif chose cartoons. It’s as simple as that,” says Kannan.

Not only standalone cartoons, but Hasif was also given an opportunity to paint for autobiographical series such as Vattiyum Mudhalum by Raju Murugan. After working as a freelance artist for two years, in 2013, he became a full-time employee at Vikatan Group. Now, his cartoons accompany editorials, a space earlier dedicated to the works of popular cartoonist Madan.

A fan and follower of American illustrator Norman Rockwell, Hasif says his initial work — digital illustrations and cartoons — often failed to appeal to a lot of fellow artists.

“They used to say cartoons should not have colours in it and it must be hand-drawn. But over the years, they have come to accept the power of technology,” he says. Today at least half a dozen artists are following Hasif’s style with digital cartoons.

But more than the medium of art, it’s his style that makes Hasif such a popular name in the state. And Vikatan has played a huge role in making that possible.

How important is media’s role

Vikatan, which was first to publish sector-wise magazines in the Tamil media industry, has a legacy of standing against the government for a cartoon.

In 1987, during MGR’s regime, Vikatan published a cartoon on its cover criticising the state Assembly. Alleging that it has hurt the institution, the then Speaker PH Pandian pressurised the then editor of the magazine, S Balasubramanian, to apologise. Instead, Balasubramanian went to the Madras High Court. The court summoned Pandian but he refused to turn up and claimed he got “sky-high powers”. Balasubramanian was sentenced to jail for three months.

This created a commotion in the publishing industry. Due to the support he got from various media houses, MGR intervened and Balasubramanian was released after three days. The court also ordered the government to pay a fine of Rs 1,000 to Balasubramanian. That cheque was later framed and kept in the magazine office. It still remains the biggest legacy of Vikatan.

Hasif is every bit aware of Vikatan’s contributions in shaping his individual career.

“I was a reader of Ananda Vikatan first. Then I joined as a student reporter there. Then I evolved into a cartoonist and now I am an employee of this magazine which carries such a legacy. All I wanted in my life was to become an artist. Hope, I achieved that.”

And that’s where the role of media organisations and the stand taken by them becomes so important for journalists and artists working for them.

In a democracy, when the opposition parties are not strong enough and most sections of the media choose to underplay the dangers, it is art which takes the role of a tough Opposition. The governments should consider cartoons and other works as suggestions and not as criticisms, Hasif says.

To his credit, one of his artwork has been placed in the Society of Illustrators, New York. He is the first Tamil artist whose work has been exhibited there.

“I am an ordinary man like you. What affects you also affects me. I too have the same kind of anger that you have against injustice. That reflects in my cartoons and people who are able to connect with it emotionally, appreciated it. The everyday conversations and what I observe feed my imagination.”

“For example, when Jayalalithaa died, I drew a cartoon. The word Unmai (truth) was written on a coffer and the aides of Jayalalithaa throwing a fistful of mud inside the grave. The phrase Unmaiyai kuzhi thondi pudhaithal (burying the truth) is used by Tamils in common parlance. That became an inspiration behind the illustration,” he explains.

So, how far has Hasif traveled? As an editor who brought Hasif into the media, what does Kannan feel about the heights Hasif has touched?

“Initially, his name itself was a problem. It’s a bit tricky… especially for a Muslim to criticise the saffron powers. He couldn’t avoid it either. Hasif carries on with his job without any hesitation. The honesty and truthfulness in his illustrations became his identity now. That continues to protect him,” Kannan says.

Talking about Hasif’s works, environmental activist G Sundarrajan says, the clarity in his work has won him the fans. “It’s simple and straight, as it should be.”

In an effort to convey the message, Hasif’s work does not lose its artistic essence, says political commentator Kumaresan.

A serious job

“His work doesn’t remain limited to the pages of a magazine alone. I remember one incident where his art became a campaigning tool against the government. In a demonstration organised in Chennai by the Tamil Nadu Progressive Writers and Artists Association to condemn the Thoothukudi police shooting, Hasif’s illustration was printed on a flex banner and displayed prominently. It created major ‘inconvenience’ to the police and they removed it by force,” says Kumaresan.

Such was the power of that illustration, Kumaresan gushes.

So, is Hasif not scared of anyone?

“I have never worried much about my cartoons. I don’t think they would land me in jail. However, my name has been included in some of the defamation cases along with editors and publishers,” Hasif says.

While many in north India feel that artists in the southern states enjoy a comparatively democratic space (because of the overall cultural atmosphere), Hasif breaks the ‘myth’. “I have some cartoonist friends in north India. Sometimes, we do discuss art and politics. What I understand is there isn’t much difference. Whatever freedom I enjoy here, they too have the same.”

But yes, editorially, it may not be the same, he adds.

And then there are the bevy of trolls on social media. But should that stop one from telling the truth or expressing their views? He admits that most of the comments are vitriolic. “But I never received any murder threats,” he smiles.

“Some of my cartoons that go with the news stories take a critical look at the current political happenings. Other than that, I work on cartoons that create awareness about the importance of exercising one’s democratic rights,” he says.

And in the run-up to the elections, he is exactly doing that. “Creating awareness about the democratic festival.”

That festival, naturally, will include all the political shenanigans.