- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Athirappilly project: When people's persistence can win the good fight

For villagers living in Athirappilly-Vazhachal region in Kerala’s Thrissur district and opposing the proposed Athirappilly hydroelectric project for over three decades, the tide in Chalakudy river is turning, albeit sluggishly.

For villagers living in Athirappilly-Vazhachal region in Kerala’s Thrissur district, the tide in Chalakudy river is turning, albeit sluggishly. While people here have spent more than three decades campaigning against the proposed Athirappilly hydroelectric project, old conflicts recently resurfaced after the Kerala government extended its no-objection certificate to the state’s...

For villagers living in Athirappilly-Vazhachal region in Kerala’s Thrissur district, the tide in Chalakudy river is turning, albeit sluggishly.

While people here have spent more than three decades campaigning against the proposed Athirappilly hydroelectric project, old conflicts recently resurfaced after the Kerala government extended its no-objection certificate to the state’s electricity board. This evoked angry response across the country, ultimately forcing Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan to announce that the NOC was only part of a routine procedure and that the project with an installed capacity of 163 MW will be implemented only through a consensus decision.

Even though the government has not formally given up on the project, it looks unlikely that the state can go ahead with the proposal against the will of the people.

And this is what has kept alive the hopes of the villagers all these years.

Fighting the good fight

Over the years, the Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) has kept moving the file at regular intervals. But every time it invited huge public outcry against the project. The same happened this time as well.

In fact, the NOC provoked an enormous outpouring of support with ecologists, social activists and eminent personalities rallying behind the protesters on social media. Even the CPI, which is part of the ruling LDF government, has always been against the project.

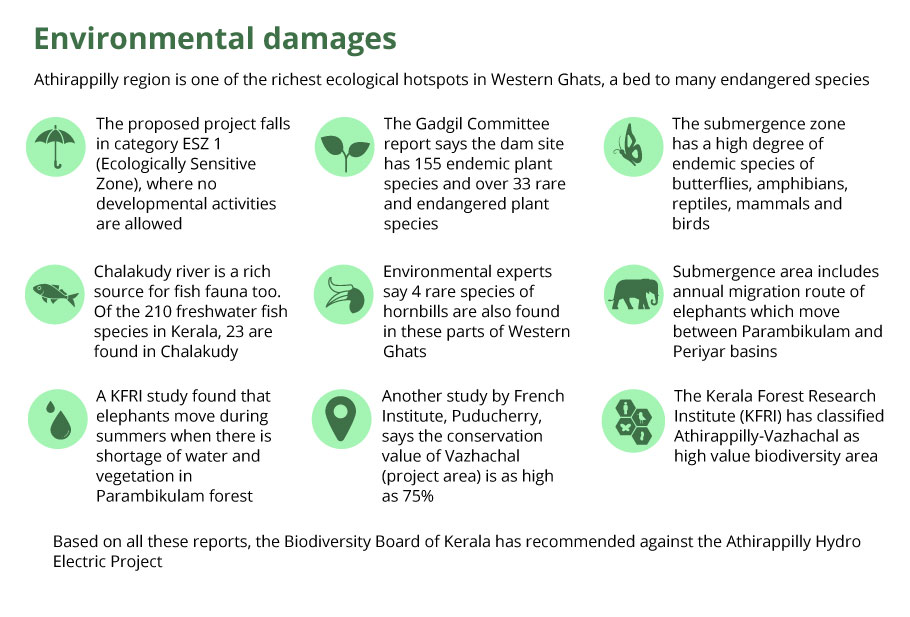

The movement against the Athirappilly project is a unique near-success story of a sustained fight led by the Chalakudy Puzha Samrakshana Samithi along with many others for over three decades. This includes movement against forcible land acquisitions and displacement of the tribal people, submersion of 168 hectare of biodiversity forest along with large number of endangered species of plants and animals besides the majestic Athirappilly waterfalls that is one of the prominent tourist attractions in southern India.

The KSEB, however, says that the claims about environmental damage are exaggerated.

According to MG Suresh Kumar, general secretary of KSEB Officers’ Association, the project, if implemented, would submerge only 28 hectares and not 168 hectares as claimed by the protesters. “The total area of the reservoir is only 104 hectares in which around 78 hectares consist of teak forests and catchment area.”

SP Ravi, secretary of Chalakudy Puzha Samrakshana Samithi, dismisses these arguments. “The KESB’s definition of forest doesn’t match with the reality.” According to Ravi, the KSEB is only trying to downplay the actual ecological damage caused by the project.

Long years of vigilance

The proposed project, if constructed, would be the seventh dam in Chalakudy river — the fifth longest river in Kerala. Ecologists warn the seventh project will toll the death knell for the little-remaining endemic species of flora and fauna in the region.

A look at the chronology of events over the years gives a fair idea of how fierce a battle was fought by the people, keeping constant vigil over authorities trying to take decisions behind their back.

The proposal for the project was submitted in 1982. In 1985, civil resistance broke out for the first time with local environmental groups and people’s collectives taking the lead.

In the next two years, Chalakudy Puzha Samrakshana Samithi (CPSS) — a voluntary organisation of activists and ecologists — was formed. As a result, the Union Ministry of Environment and Forest (MoEF) refused to give clearance to the project in 1989. This, in turn, led the KSEB to submit an alternate proposal with a few changes.

Following this, another round of fresh agitations were launched by the CPSS. This time around, massive campaigns were held in educational campuses as well. The CPSS carried out Jala Yathra (rallies) strengthening interactions with river-based communities living on the river banks.

In 1998, the project got a fresh lease of life when it got MoEF clearance based on an environment impact assessment (EIA) by the tropical Botanical Garden and Research Institute (TBGRI). The CPSS vehemently opposed the move on the grounds that no public hearing was conducted.

While the agitators and the KSEB tore into each other’s plans at debates for the next few years, the protests eventually grew beyond Kerala, and saw the participation of Narmada Bachao Andolan activist Medha Patkar and author-activist Arundhati Roy.

Following this, based on a public interest litigation filed by the CPSS, the Kerala High Court in 2001 dismissed the MoEF clearance and directed the KSEB and the ministry to conduct a public hearing and follow all mandatory procedures for environmental clearance. The KSEB did not give in and entrusted a new agency for a fresh EIA.

The public hearing conducted on February 6, 2002 in Thrissur itself turned into an organic protest, says Ravi.

“It (public hearing) was initially proposed to be conducted at a government guest house. But when we reached there, there were only a few chairs in a small room packed with KSEB representatives,” he recalls.

The CPSS, on the other hand, had gone with around 500 people to attend the hearing. “The authorities were compelled to change the venue into a bigger hall. The hearing thus ended amid high drama in which the entire people unanimously spoke against the project.”

A new EIA was asked to be conducted covering all seasons (not only monsoon) as demanded by the CPSS. The earlier EIA was apparently conducted without covering the dry seasons. This, according to the agitators, was carried out discreetly. While litigations were filed by the Kadar tribal community living in the area, EIAs and public hearings continued to face opposition by people.

The KSEB again got a clearance in 2005, which led to another round of agitations. In 2005, Chalakudy River Protection Forum (CPF), a conclave of 30 organisations was formed. The CPF-organised rallies and conventions were backed by prominent writers and cultural leaders.

“From this phase onwards, the protests were no longer an environmental movement. It turned into a people’s movement,” says Ravi.

Indefinite satyagraha

On December 23, 2005, the protesters flagged off an indefinite satyagraha.

“People belonging to all sections — auto/taxi drivers, hotel owners, merchants’ associations — were part of the struggle. Whoever came to Chalakudy to participate in the Satyagraha, hotel owners provided free food. Even the private bus operators in Chalakudy refused to accept money from passengers coming to participate in the protest.”

The 90-day long indefinite Satyagraha was called off in 2006, after the high court quashed the MoEF clearance.

While site visits, public hearings and EIAs conducted multiple times met with resistance from people, the KSEB managed to get clearance for the third time in 2007. Tribal leader VK Geetha — the first woman chieftain of a tribal community (Kadar) in Kerala — filed fresh litigations, demanding action under the Forest Rights Act, 2006.

The second phase of the indefinite satyagraha was launched on February 25, 2008.

This time, the protests were not limited to rallies or public speeches. Academic debates on the ‘biodiversity of Western Ghats’ too were arranged. Arundhati Roy participated in the public programme organised on the 100th day of Sathyagraha and declared her support to the struggle. (This satyagraha was called off after 400 days following the April 2009 general elections).

The entry of Jairam Ramesh as the Union minister for environment and forest added a new twist to the story. He rejected the KSEB’s explanations for renewal of environmental clearance, but gave it one more chance to present its case. Later, he passed the ball to the Gadgil committee.

Ramesh’s views haven’t changed. Talking to The Federal following the recent NOC by the state government, he says: “I had put a stop to it in 2010 after consulting various people in Kerala, both in the government and outside. This project will cause immense ecological damage. It is atrocious that the LDF is reviving this project. I hope people of Kerala will ensure that this madness doesn’t proceed.”

Meanwhile, the Gadgil committee in 2011 rejected the project. However, this was soon reviewed by the Kasturirangan Committee, which too identified the project area as eco-sensitive and refused to recommend clearance. But it permitted the KSEB to make a fresh pitch for MoEF clearance. After the NDA government came to power in 2014, the MoEF withdrew the show cause notice served to the KSEB by the UPA government and extended the green clearance until 2017.

According to the CPSS, the government renewed the clearance, without following any procedure, three years after it had lapsed. On the other hand, the Left government led by Pinarayi Vijayan in Kerala that came to power in 2016 made declarations of going ahead with the project, inviting intense protests across all sections of the society.

The validity of the green clearance lapsed on July 17, 2017, following which the Athirappilly Project, for all practical purposes, was shelved. After 30 years, the protests were finally called off.

Changing course

Much water has flowed down the Chalakudy river in the past three decades.

While the local units of most political parties firmly stood behind the protesters (even the CPM initially backed them), those who once supported the project seems to have changed their mind, albeit for different reasons. “When we consider the cost of the project, the question is if we really need to go for it or not. The cost of a hydroelectric project is invariably high,” says M Sivasankaran IAS, principal secretary to the chief minister and former chairman of KSEB.

He, however, maintains that the claims over ecological damages are “highly exaggerated”.

However, under changed circumstances in which Kerala is capable of purchasing power from other states, Sivasankaran feels there is no need to push for the Athirappilly project.

Others like CPI leader and Rajya Sabha MP Binoy Viswam believes that no political party following Marxist ideology can think of causing such heavy damages to the environment. “For that matter, I don’t think the LDF government or the CPM would go for a hydroelectric project in an ecologically fragile zone,” he adds.

Ravi fondly recollects the initial days of the struggle. “CPM had to distance itself later, but the CPI continued with their unconditional support to the protestors.”

Ravi says the protests against Athirappilly project has been so far successful in stonewalling the proposed project because of the participation of people from all categories. “Left-leaning organisations like the Sasthra Sahithya Parishad stood with the movement despite differences within their organisations.”

Now that the controversy has resurfaced, Ravi feels, if push comes to shove, he and others are ready to continue the struggle.

“We formally called off the protests in August 2017. I don’t think the government would go ahead with this plan. However, if they intend to go ahead with the project, we are always ready to put up a fight,” says Ravi.