- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

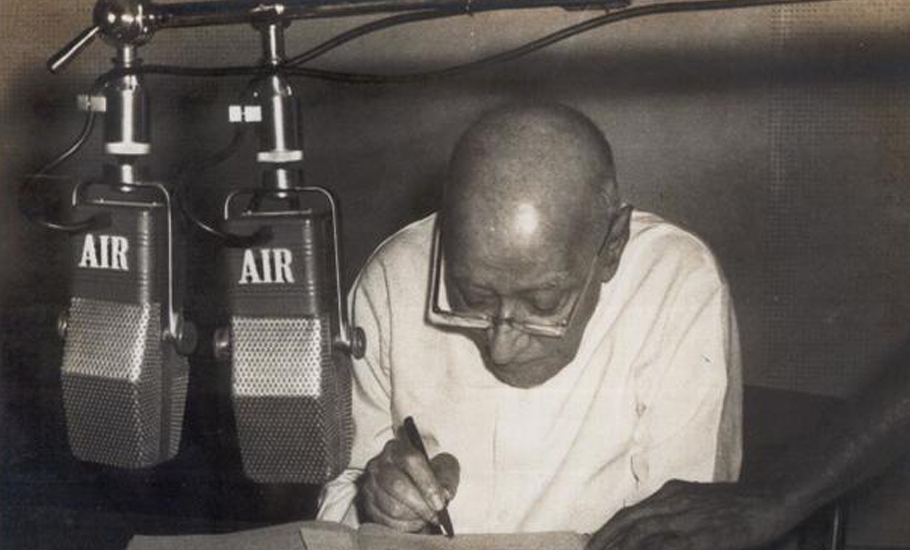

AIR overhaul: Is this the death of local radio as we know it?

On October 18, Geetha Ramanand, a veena artist and an avid radio listener was in for a rude shock when Amruthavarshini FM (100.1), a dedicated classical music station, went offline. She later realised the regional Kannada radio channel, which was part of Akashvani Bengaluru, ceased to exist and was merged with Raagam, a multilingual national channel. For 70-year-old Ramanand, who has worked...

On October 18, Geetha Ramanand, a veena artist and an avid radio listener was in for a rude shock when Amruthavarshini FM (100.1), a dedicated classical music station, went offline.

She later realised the regional Kannada radio channel, which was part of Akashvani Bengaluru, ceased to exist and was merged with Raagam, a multilingual national channel.

For 70-year-old Ramanand, who has worked with All India Radio (AIR) for 36 years and performed and produced several music shows, it’s the end of an era. She nurtured the channel’s growth from its inception in 2002 to 2011, when she retired.

Born into a family of music connoisseurs, Ramanand who holds a master’s degree in music, was also a nominated member of the expert committee on Carnatic Music, Union Ministry of Culture.

Ramanand feels that merging Amruthavarshini with a national radio channel would take away the opportunity available for young artists and affect the regional content creation. Around 3,000 musicians across the state were involved in producing content at regular intervals for Amruthavarshini radio, she says.

“Local artists from Karnataka used to produce content, classical and Hindustani music, for eight-and-a-half hours every day for Amruthavarshini FM. Now, they have to compete for space with other state artists as they would barely get a two-hour slot,” Ramanand says.

Raagam 24/7 is being aired for 17 hours on digital and satellite radio. It derives content from 14 AIR stations across the country, including Bengaluru.

“We not only performed musical shows but also discussed theoretical aspects and gave music lessons to encourage listeners. So shutting regional stations will certainly be a setback for artists and classical music lovers,” she adds.

Ramanand is shocked by the fact that the change happened without any prior announcement, notification or wide consultation.

While artists are not dependent on the radio programmers for their livelihood, the larger worry is that local culture and regional talent are at stake. Young classical musicians took pride in performing for AIR and the gradation that the public broadcaster gave (B, B- High, A, Top) for artists set a benchmark for the industry. Many were and still are eager to perform on AIR to gain experience and exposure.

“It’s really sad the next generation will lose out. This is just the beginning of things to come,” says Giridhar Udupa, a Ghatam (percussion instrument) player. Udupa, too, occasionally performs for AIR.

AIR, he says, used to have 30-40 full-time musicians who also produced content for the station in Karnataka, but now there’s only one person. “The government cites commercial reasons and going digital for discontinuing certain operations. But not many access radio through the internet,” he adds.

You can't add multiple timelines in the same post, page or custom post type.

Over the past decade, more than 70 YouTube channels have been created by Prasar Bharti to disseminate audio/video content. Over 248 AIR channels have also been made available on “NewsonAir” app on Android and iOS mobile platforms.

Udupa, Ramanand and 28 other musicians met in Bengaluru in October last week and formed the ‘Classical Musicians Forum of Karnataka’ to collectively highlight the issue and requested musicians not to sign any public programme contracts with the radio station until Amruthavarishini is restored.

Chalapathy S Srinivas, a Bengaluru-based advocate, even wrote a letter to Prime Minister Narendra Modi requesting him to intervene and restore Amruthavarshini FM. After not getting any response for two weeks, Srinivas now plans to file a PIL in court.

The developments have led to speculations over whether Prasar Bharati is inching towards ‘One Nation, One Radio, One Programme’ goal to further its agenda.

Discontent across southern states

“Not everybody listens to the same kind of music. The audience sitting in Karnataka may not consume content from other states. It applies to all states. So the government cannot force one to listen to what it wishes to broadcast,” Srinivas says.

Discontent is brewing with radio listeners and employees of AIR not just in Karnataka, but also in neighbouring Tamil Nadu and Kerala.

In Kerala, employees of Doordarshan and All India Radio took to the streets and protested against the shutting down of terrestrial services. The services were shut down citing lack of profits.

Tamil Nadu AIR’s recent proposal to convert four primary radio channels of the state and Puducherry into relay stations, caused consternation among radio listeners, including the farming community.

Vela Senthil, a farmer based in Tiruvarur, one of the Delta districts in Tamil Nadu, remembers how AIR programmes created awareness about a rice variety introduced during the first phase of the green revolution. “People called ADT-27 as ‘radio rice’. Such was the impact of broadcasting then,” he said.

“Currently, we get updates about agricultural activities on AIR which helps us to make informed decisions about the climate risks, sowing, pest control and more. But we doubt if in the future we will get region-specific news and programmes,” said Senthil. He’s also the secretary of Radio Listeners Welfare Association, Tiruvarur.

He fears that the centralisation of content production will compromise on the local flavour. Senthil says if there is a programme on groundnuts or cotton from other stations aired for listeners in a paddy-rich region, it will not be of much help.

But SS Pandian, a former AIR employee and the general secretary of Indian Broadcasters Forum, has a different take. He says artists, who got an opportunity to display their talent at particular stations, will now have the chance to showcase their work beyond one station or state.

“Earlier programmes were aired through terrestrial transmitters. So we needed ‘relay centres’ in many areas. Now, it is being carried through satellites and hence the relay centres are becoming redundant and getting closed. He feels it’s a cost-effective measure that would benefit the public broadcaster.

The Federal’s repeated attempts to contact Saradha Jambunathan, programme head, AIR Chennai, failed to elicit any response.

The cost of new tech

Rolling out broadcasting reforms at Doordarshan and All India Radio over the last couple of years, Prasar Bharati has been swiftly phasing out obsolete broadcasting technologies such as Analog Terrestrial TV Transmitters. Now, it plans to phase out 412 transmitters by the end of 2021-22.

“Analog Terrestrial TV is an obsolete technology and phase-out of the same is in both public and national interest as it makes valuable spectrum available for new and emerging technologies such as 5G apart from reducing wasteful expenditure on power,” Ministry of Information and Broadcasting said in a release on October 9.

While the decision of the Prasar Bharati to reinvent itself through various measures is being welcomed, its recent moves – like converting the primary stations into relay stations, decreasing the budget allocated for producing programmes to less than 50 per cent, failure to fill up vacant posts – have caused dissatisfaction.

According to the government’s own submission in Parliament, 2,156 of the 7,052 sanctioned posts in the engineering wing (30 per cent) and 4,151 of the 6,075 posts (a whopping 68 per cent) are lying vacant as of March 2021.

Researchers feel AIR should be given a new lease of life by bringing in youngsters. Even the government said the manpower audit of Prasar Bharati revealed key gaps in the existing manpower mix and skill capabilities due to changes in technology and automation.

“The manpower audit has recommended several steps to phase out obsolete technologies and unviable services, automate and IT enable key operations and to outsource non-core activities so as to bring the manpower requirements in line with global best practices in public broadcasting,” the Information and Broadcasting Ministry said in Parliament.

Running behind time

Being one of the biggest democracies in the world with over 1.3 billion people, India continues to hold a state monopoly in radio news. Only the AIR is permitted to broadcast news and current affairs programmes. Private broadcasters running FM radios have the license to provide music and entertainment content, but not news.

BBC Radio in the UK commands 50.9 per cent market share with radio listeners tuning in for more than 15 hours a week. India does not even have proper data to track radio trends.

In October, Prasar Bharati for the first time quantified listenership in absolute numbers and said it had 9.45 million users tuning in across 10 cities.

The government boasts that AIR’s service comprises 470 broadcasting centres located across the country, covering nearly 92 per cent of the country’s area and 99.19 per cent of the total population. But this is also a fact that the AIR mostly airs government propaganda and fails to attract urban listeners, who have varied choices powered by growing technology.

Podcast networks are slowly emerging to make a mark in India with leading news organisations, researchers and independent content producers creating content on science, culture, food, current affairs, religion and more. But AIR has failed to keep pace with it.

Its app, NewsonAir on iPhone does not even play content in regional languages. If one selects Tamil language, a bug in the app automatically shuts the app. Besides, featuring right on top of the screen, Sardar Vallabhai Patel memorial lecture appears to be the lead programme. Many feel private podcasters will soon leave AIR squabbling for content in the years to come.

Its revenues are on a steady decline. While AIR earned Rs 465.41 crore, 2017-18, it reduced to Rs 305.23 crore in 2019-20, and further to Rs 108.74 crore (eight months) in 2021, as per the Information and Broadcasting Ministry. The revenues generated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ‘Mann Ki Baat’ programme (started in 2014), dropped by 90 per cent in the last fiscal from the peak in 2017-18, according to a written reply submitted by the I&B Ministry in Rajya Sabha.

V Kumar, chief executive officer, Air Media Solutions, facilitates NGOs to launch their own community radio stations. He says AIR has failed to generate greater income and its business model has failed.

“The AIR stations in Tamil Nadu are given 20 kW frequency coverage. That enables them to reach all 38 districts. Having such a resource, they can bring in a lot of advertisements at a good rate. But the sector has become just another lethargic government office,” he adds. “Employees are not showing any interest in developing the station because of the innate internal politics.”

According to industry experts, the AIR has failed in keeping with time because of its rigid policies. It was only after a Supreme Court judgment in 1995, which said airwaves are a natural resource and belong to the people, that community radios started to emerge in India. But it hasn’t seen any phenomenal growth. Today, India has 329 community radio stations rising from 162 in 2011.

“If one applies for a license to run a radio station abroad, they may get permission within a week. But here, even to start a community radio, you have to run from pillar to post,” says T Jaisakthivel, assistant professor, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Madras.

“In the UK, there is ‘Restricted Service License’ (RSL) given to the individuals or companies who like to run a radio for a short period, say for a week or a month. But we don’t have that liberty here,” he adds.

According to Father Bijo Thomas, station director of Radio Mattoli community radio station in Kerala’s Wayanad, at least the AIR can share its programmes when private radios are not allowed to broadcast news.

“The AIR produces programmes in several regional languages in the country. Most content is related to the development sector. Once the programme is done by AIR, it can be shared with other community radios for free and thereby it can reach a wider audience,” Thomas adds.