- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

AFSPA: How the clock turned 24 years back in Nagaland

At 77, former Nagaland chief minister KL Chishi has almost lost count of the number of times his home state has erupted into flames in the past several decades. The protests raging today and in the past on the streets of the state had varying triggers. But the fuel has been almost always familiar — atrocities against civilians by the Indian armed forces. Of course, the outcome of...

At 77, former Nagaland chief minister KL Chishi has almost lost count of the number of times his home state has erupted into flames in the past several decades. The protests raging today and in the past on the streets of the state had varying triggers. But the fuel has been almost always familiar — atrocities against civilians by the Indian armed forces. Of course, the outcome of these protests too have been familiar — a few words of condemnation by the central government and a handful of promises that were never kept.

The massive rallies and shrill sloganeering against Indian security forces that the state is witnessing again this winter are a throwback to the turbulent past that many thought Nagaland had left behind in 1997 (when the Naga peace process started with a ceasefire agreement between the NSCN-IM and central government).

The last such massive outburst against the Indian army in the state was in the mid-90s in the aftermath of a series of major incidents of atrocities against civilians between 1994 and 1995, recalled Chishi.

He was referring to the incidents of shootings, arsons and rape by security forces in Mokokchung, Kohima and Akuloto that drew countrywide condemnation.

In retaliation to an attack on a patrol of the Maratha Light Infantry (MLI) in the heart of the Mokokchung town by insurgents on December 27, 1994, army jawans set on fire several houses and shops with civilians trapped inside. Eight persons were burnt to death in the incident. Four women were also allegedly raped at gunpoint, according to the depositions they made before the Red Cross Society and a judicial inquiry commission.

In another incident in 1995, this time in the state capital Kohima, 16 Rashtriya Rifles went berserk indiscriminately firing mortars and bullets on civilians killing seven persons and injuring 20 others after their 63-vehicles convoy was allegedly attacked by Naga militants. Eyewitnesses and police, however, refuted the army’s claim. They said that a tyre of one of the vehicles in the army convoy had burst. The RR personnel immediately started shooting, mistaking the sound of a tyre burst as an attack on them, according to the police’s accounts.

An inquiry commission later noted that the RR personnel had “acted in a most irresponsible manner” and termed the action as “cold blooded murder of innocent civilians, some within their residential houses.”

In Akuloto, the Assam Rifles during a combing operation in January 1995, burnt down some houses on suspicion that the residents were harbouring militants after one of its posts was attacked by insurgents. When a woman refused to come out of her house she was shot dead and her three-month-old child was injured.

The above incidents were not isolated events of killings and excesses by the army. There had been numerous such instances of attacks on lives and properties not only in Nagaland but also in other insurgency-affected northeastern states.

Such use of excessive force by the armed forces time-and-again proved counterproductive in containing insurgency as it antagonised innocent civilian victims just as it has now happened in Nagaland.

On boil, again

The latest flare up has been triggered by the killing of at least 13 civilians in the state’s remote Mon district in a highly suspicious counter-insurgency operation conducted by a decorated commando unit of the army earlier this month.

A team of 21 Para Special Forces of the Army based in neighbouring Assam entered into Nagaland apparently without informing the local Assam Rifles unit to lay an ambush on “insurgents” based on what they claimed was “credible intelligence” on December 4.

The operation, however, went horribly wrong as those who were tipped off as militants turned out to be miners returning home in a vehicle from a nearby coal mine. The commandos, without cross-verifying the identity of the miners, fired on them, killing six and injuring two others.

Not stopping at that, they allegedly tried to hide the bodies, wrapping them under tarpaulins and loading them on another vehicle, resulting in a clash with local villagers who had rushed to the spot after hearing gunshots. Seven more villagers were killed in the ensuing clash. The army said one of its soldiers was also killed.

Some villagers even alleged that the army tried to put olive green army fatigues on the slain miners in a bid to pass them off as militants.

A preliminary investigation report filed recently by the Nagaland police, after its chief T John Longkumer and commissioner R Mor visited the incident spot, pointed out that the commandos had traveled in civilian vehicles, sporting fake number plates.

The report also claimed that the firing was unprovoked and without any warning. The police’s preliminary investigation further revealed that the vehicle was fired from the front. This contradicted Union home minister Amit Shah’s statement in Parliament that the commandos fired when the vehicle tried to flee after being asked to stop. Most bullets would hit the back or side of the vehicle if it had tried to speed away and not in the front as the police found in this case.

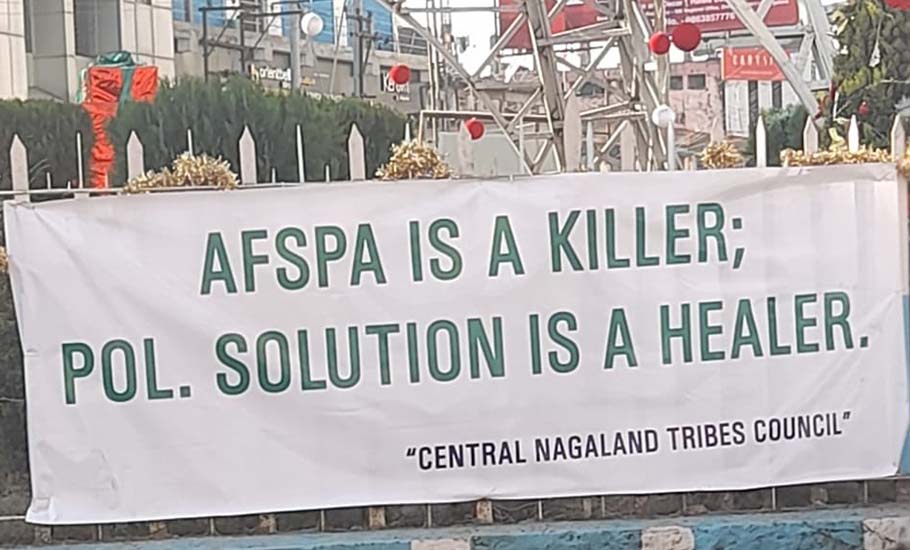

The incident sparked furious protests across the state. A conglomerate of apex bodies of six Naga tribes, the Eastern Nagaland Peoples’ Organisation (ENPO) even started a “non-cooperation” movement against the armed forces, seeking justice for those killed and repeal of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act.

The never-ending nightmare

The AFSPA enacted in 1958 to quell Naga insurgency is seen as detrimental in pursuance of justice as section six of the Act says “no prosecution, suit or any other legal proceeding can be instituted, except with the previous sanction of the Central Government against anything done or purported to be done in exercise of the powers conferred by the Act.”

Simply put, it denies the state government the power to prosecute any army personnel guilty of violating human rights without the prior permission of the central government.

Even in the past incidents of excesses by the security forces, the provision of the law provided a shield to the men in uniform from legal proceedings.

Apart from giving legal protection, it also provides “special powers” to the armed forces to open fire or use force, even causing death, against any person who is deemed flouting any law or order. Further, as per the provision of the law no arrest and search warrants are required for any operation.

These unbridled power and protection are at times, if not often, misused to the extent of running a parallel administration by the security forces. So much so that the Manipur government in 1987 had to submit an unprecedented memorandum to the Union home minister complaining how the Assam Rifles had undermined the civil administration. It stated: “Civil law has ceased to operate in Senapati district of Manipur due to excesses committed by the Assam Rifles with complete disregard shown to civil administration. The Assam Rifles are running a parallel administration in the area.”

Given the controversial nature of the act and its track record of shielding the guilty, it has been naturally feared that once again the controversial law would prevent the delivery of justice.

“The Special Investigation Team (SIT) constituted by the Nagaland government to probe the December 4 incident would not do justice to the willful acts of the Indian armed forces under the protection of the repressive AFSPA,” the Naga Students’ Federation (NSF) said in a memorandum sent to Prime Minister Narendra Modi on December 17 seeking repeal of the law. Even a special one-day session of the Nagaland assembly on December 20 adopted a unanimous resolution seeking repeal of the controversial Act from the Northeast in general and Nagaland in particular.

Earlier, the Nagaland government and even the state’s BJP unit also backed the demand for scrapping of the law. BJP chief minister of Manipur N Biren Singh and Meghalaya chief minister Conrad Sangma (a BJP ally) too called for the repeal of the law as the demand is spilling over from Nagaland to other states.

Apart from Nagaland, the AFSPA at present is in force in Manipur (excluding capital Imphal), Assam and parts of Arunachal Pradesh, as well as Jammu and Kashmir.

What lies ahead

The scrapping of the act alone, however, is unlikely to drastically stop atrocities unless the security forces are made accountable to the elected civil administration of the states during counter-insurgency operation, points out Chishi.

He said neither the army jawans nor their superiors have any training in maintaining civilian law and order or policing as they are trained to shoot in a war-like situation and, as such, they are “trigger-happy”.

Buttressing the former chief minister’s argument, veteran commentator on northeast affairs, Dipankar Roy, pointed out that the AFSPA was not in force in Mizoram, then a district of Assam, when the Indian air force strafed Aizawl on March 5, 1966.

The air raid– the first and the only time the Indian Air Force was used to attack its own people– killed many innocents and severely destroyed the four largest areas of the town – Republic Veng, Hmeichche Veng, Dawrpui Veng and Chhinga Veng.

“The town was strewn with bodies as terrified civilians ran away to jungles away from Aizawl. I don’t remember exactly after how many days, but I do remember a Welsh missionary, Alwyn Roberts, and his team of around 20 people going around the town collecting bodies for burial,” recalled Lalhmerliani Fanai, a former senior announcer of the All India Radio, Aizawl. Fanai was about 13 years old at the time of the air raids.

“I wonder if Maoist insurgency can be dealt with by the state police, why not the northeast militants?” she asked, a question many in the Northeast would like the Centre to answer.