- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Abhinandan's folk: Jains who are Tamils but don't eat onions

When Indian Air Force fighter pilot Abhinandan Vardhaman was held hostage by Pakistan a month back, support for his release and pride over his nativity swelled in equal measure in his home State of Tamil Nadu. Abhinandan didn’t quite sound like a Tamil name. Was he from Kerala? they wondered. Abhinandan Vardhaman comes from the community of Tamil Jains, native Tamil speakers whose...

When Indian Air Force fighter pilot Abhinandan Vardhaman was held hostage by Pakistan a month back, support for his release and pride over his nativity swelled in equal measure in his home State of Tamil Nadu. Abhinandan didn’t quite sound like a Tamil name. Was he from Kerala? they wondered.

Abhinandan Vardhaman comes from the community of Tamil Jains, native Tamil speakers whose heritage goes back to the earliest recorded history of Tamils. “Abhinandan comes from a traditional Tamil samanar family. His mother Shoba, a doctor, and father Vardhaman, a retired air marshal, hail from Tiruppanamoor and Karanthai in Tiruvannamalai district respectively,” says AP Aravazhi, a Tamil Jain scholar and a retired district education officer who is related to the family.

Abhinandhan is named after the fourth of the 24 Jain ‘tirthankars’ and Vardhaman is also how Bhagavan Mahavir, the last of the ‘tirthankars’, is otherwise called.

Jains of Tamil origin are called ‘samanars’ whose population, according to their recent community census, is pegged at 40,000. They belong to the ‘digambar’ sect and are strict vegetarians. Their code prohibits eating onions, too, just like Jains in northern India.

Concentrated in the northern districts of Tamil Nadu, they were originally farmers. But the more recent generations have taken up other professions and migrated to metros and abroad for livelihood.

While Jains in general are a minority among religious minorities, Tamil ‘samanars’ are a micro community. According to a community census conducted in 2015, they constitute 0.12 per cent of Tamil Nadu’s population. It was only in January 2014 that the Jains were accorded minority status by the Congress-led UPA government which, some in the community say, does not provide reservation in education and employment.

“The classification helps us get loans at lower interest rate and start small businesses. While we are nowhere near the rich Jains found in northern India, the state government should consider our long-pending demand for quota in government jobs and education. The presence of ‘digambarars’ in the land of Tamils dates back to 3rd century BCE. We are an indigenous population whose identity is rooted in the state,” says S Anantharaj, secretary of Madurai Jain Heritage Centre.

What the Jains are doing to preserve their heritage

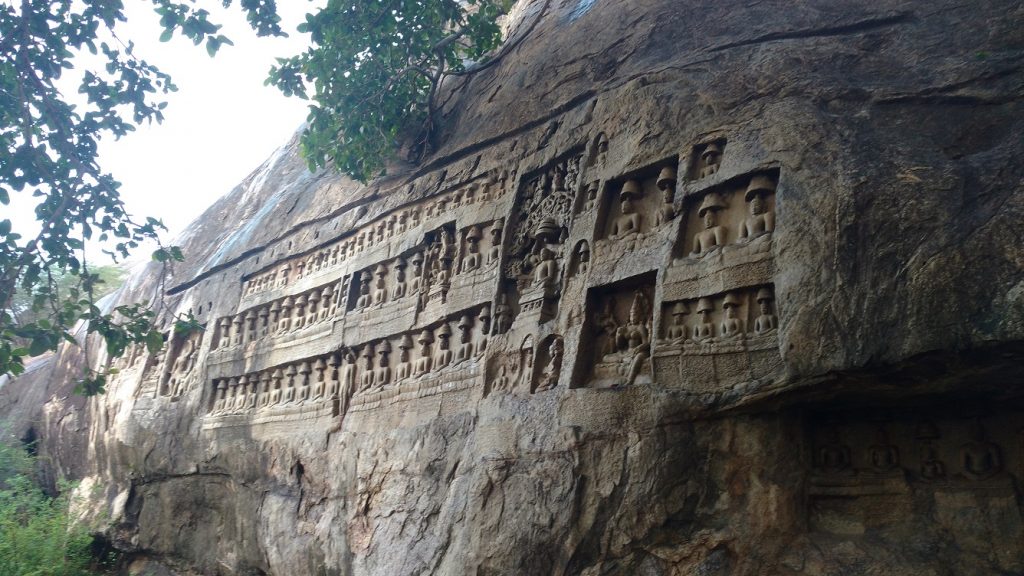

With the help of local enthusiasts, the ‘samanars’ have taken the initiative to preserve and restore the rich Jain heritage found in the form of rock-cut monuments, caves, bas-reliefs, sculptures and inscriptions dotting the state. While a majority of them have either been completely destroyed or partially damaged, there are still quite a lot of Jain heritage structures in the state that can be restored and preserved for posterity.

With the help of like-minded people and patrons, Anantharaj, a resident of Vandavasi, set up the Madurai Jain Heritage Centre at Melakuyilkudi, famously called Samanar Malai, in Madurai district to facilitate research students, archaeologists and art historians studying Jain heritage. The institute is actively involved in preserving the hills having Jain sculptures and engravings from quarries and vandalism.

Anantharaj says there are nearly 450 Jain sites across the state, majority of them being in Madurai, Tiruvannamalai, Villupuram and Kancheepuram districts. More than 100 abodes of Jain monks in natural caverns have been discovered by archaeologists in the last five decades. “Unfortunately, several of them have either been abandoned or fallen prey to quarrying,” he laments.

AP Aravazhi, who fought a legal battle to save a Jain site at Onambakkam in Kancheepuram district, endorses Anantharaj’s view.

T Lajapathi Roy, a lawyer and Jain heritage enthusiast, records in his book ‘Mathirai’: There were 14 popular Jain abodes in Madurai. Numerous Jain temples in these places were converted into Hindu temples. The Jain temple behind Tirupparankundram was converted into a Hindu Shaivaite temple in 1216 A D and the altered temple is now called Umaiyandavar temple.”

In a petition to the Madurai bench of the Madras High Court, Anantharaj said the Vikramangalam site has not been given enough protection despite being declared as an ancient monument, while the Arittapatti caves are used as cattle sheds.

Jain sites converted to Hinduism

A ‘sivalingam’ has was recently installed in the Yanaimalai Jainbed in violation of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act and Rules, while the Thiruvathavur caves around which quarrying has been done to a depth of over 100 feet is left unfenced, the petition said. Anantharaj had prayed the court to appoint an expert committee to study the 101 Jain monuments in the southern districts and suggest measures for their protection.

In an interim order, a bench comprising justices N Kirubakaran and S S Sundar observed, “These heritage sites are older than Christ. They are dated 300 BC. Not only the heritage of the place but also the antiquity of Tamil is exhibited through Tamil Brahmi inscriptions found there. According to the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), about 55,000 (55%) epigraphical inscriptions found in India are in Tamil language.”

Stating that no other religious symbol or idol can be placed atop the 2,300-year-old monuments, the court asked the ASI and state archaeology department to furnish the number of sites that have not been declared as ancient monuments when they fall under the category and the steps taken to preserve them.

In a major relief, awareness among locals, especially in Madurai, about the historical importance of Jain monuments has increased due to the efforts of voluntary organisations like Green Walk that conducts monthly walk to these sites nestled amidst the hills in the city. A Muthukrishnan, a Green Walk founder, deplores the absence of lessons on Jain culture and antiquity in Tamil Nadu, in school history books.

But the presence of Jains, their literature and culture in the state, is evident from the contribution of the ‘samanars’ to Tamil literature.

Quoting Jeevabandhu TS Sripal’s work ‘Thamizhagathil Jainam’, Aravazhi says, “Of the 104 Jain books in Tamil language, 52 were destroyed during the conflict with Shaivism. It included 26 literary works like ‘Tholkappiam’, the epics of ‘Silappathikaram’, ‘Seevaga Chinthamani’ and ‘Valayapathi’, 20 grammar books, 14 works on ethics, nine on music, seven on mathematics and five on logic.”

In his foreword to the book ‘Jainism in Tamil Nadu’, late Chief Minister late M Karunanidhi wrote, “The contribution of Jain ascetics and scholars to Tamil literature is innumerable. In short, if their works are excluded, the Tamil literary world will remain empty.” Distinguished Czech philologist Dr Kamil Vaclav Zvelebil once said, “Minus the contributions of Tamil speaking Jains in Tamil Nadu, there will be nothing to be noted in the field of Tamil literature.”

The state of Jain heritage, however, leaves a lot to be desired. The ‘samanar’ community, said to have shrunk in population after the infamous impalement of 8,000 Jains on the orders of a Pandyan king in Madurai in the 7th century, is struggling hard to maintain Jain temples.

Taking control of what is ‘theirs’

Aravazhi says there are 110 “living” Jain temples under their control in Vandavasi, Villupuram and surrounding villages, the most modern of which is Mahavir Dhinalayam in Vandavasi which was renovated at a cost of Rs1.25 crore two years ago. Aravazhi and Anantharaj say it has become difficult for the community to maintain the existing temples and keep the heritage intact in the face of the migration of young members of the community to cities and abroad.These temples or the innumerable monuments are rarely visited by the North Indian Jain community living in the state. “Most of them belong to the ‘svetambar’ sect (that believes that the practice of nudity is not essential to attain liberation). Even the ‘digambars’ among them have exclusive temples and hardly mingle with us,” Aravazhi says.

But their major grouse is against the governments for allowing the huge number of heritage sites to ruin.